Automatically Charging Youth as Adults

Automatic charging or "auto-charging" is one of several pathways that send people under 18 years old into the adult criminal legal system. Twenty-eight states and the District of Columbia have automatic charging provisions.

Related to: Youth Justice, Racial Justice

The youth justice system was created because youth are different from adults.1 State departments of juvenile justice have purpose clauses affirming that rehabilitation is their primary goal. In the youth justice system, youth have access to developmentally appropriate services that are not available in the adult criminal legal system. Sending youth to the adult criminal justice system, for any offense, harms youth wellbeing and community safety.

A better understanding of adolescent development has contributed to a nationwide decline in youth incarcerated in adult prisons and jails, from a peak of 14,500 in 1997 to 2,513 in 2023. At the same time, 29,300 were held in juvenile justice facilities.2 Policymakers should work to advance, rather than reverse, this progress and reject mechanisms, such as automatic charging, that funnel children into the adult criminal legal system.

What is Automatic Charging?

Automatic charging, or “auto-charging,” is one of several pathways that send people under 18 years old into the adult criminal legal system. State auto-charging statutes specify offenses and age requirements where a youth must be charged in adult court. This is called automatic because there is essentially no review of the case before it starts in adult criminal court.

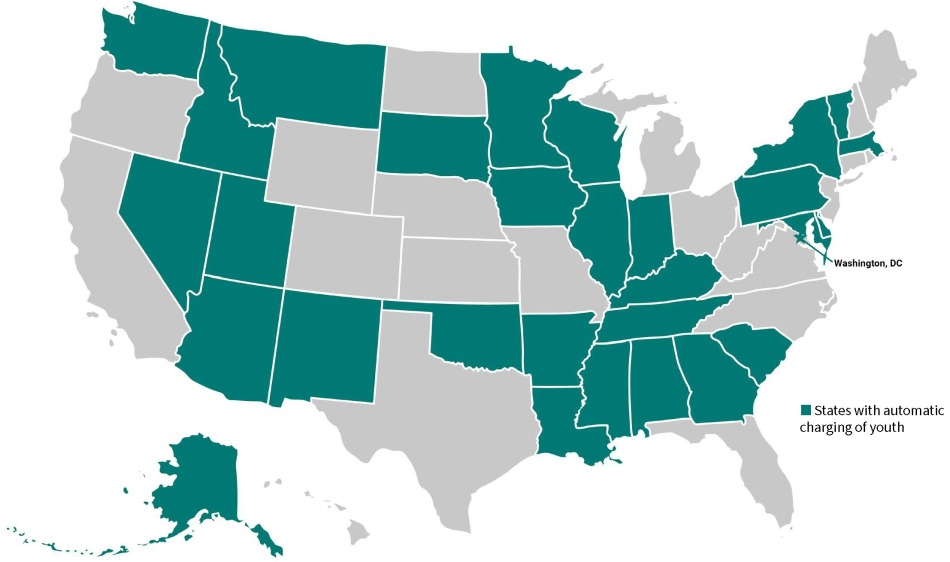

States with Automatic Charging Laws

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sickmund, M., and Hurst H. (2022). Youth and the juvenile justice system: 2022 national report. National Center for Juvenile Justice

Other terms used to describe the practice include “automatic transfer” or “statutory exclusion.”

National Scope of Automatic Charging

Currently, every state has at least one transfer mechanism that allows youth to be charged as adults in the adult criminal legal system, and most states have multiple mechanisms.3 Twenty-eight states and the District of Columbia have automatic charging provisions.4

There is limited data on the scope of automatic charging. In 2019, automatic charging combined with prosecutorial waivers led an estimated 8,900 youth to adult court.5 Prosecutorial waivers are another pathway that sends youth to adult court, by which prosecutors, with limitations by age and offense, have sole discretion over whether or not to start a case in adult court.6

Automatically Charging Youth as Adults is Harmful

Charging youth as if they were adults harms youth wellbeing and community safety. Automatic charging is particularly pernicious because there is no check on the process.

Charging youth as adults increases reoffending and harms public safety

Sending youth to the adult criminal justice system, for any offense, harms public safety because youth charged in adult court are more likely to commit future offenses, and more likely to commit the most violent offenses, than similarly situated peers retained in the juvenile courts.7

There are staggering racial disparities in youth charged as if they are adults

There is scant data on the national scope of automatic charging, but state data on youth charged as adults are alarming. Between 2009 and 2024, 80% of Maryland youth charged as adults were Black (with no data on the proportion that is Latino).8 In 2017, 84% of Alabama youth charged as adults were Black (with no data on the proportion that is Latino).9 In Nebraska, 36% and 20% of youth transferred to adult courts on felonies were Black or Latino, respectively.10

Charging youth as adults goes against adolescent brain development research

Children and teenagers are not simply little adults. According to a large body of research on adolescent brain development, sections of the brain dedicated to impulse control, weighing consequences, and regulating emotions are still developing during late adolescence.11 The vast majority of youth age out of delinquency. In fact, most youth (63%) who enter the justice system for delinquency never return to court on delinquency charges.12

Youth charged as adults do not have access to appropriate treatment and resources

Youth incarcerated in adult jails and prisons do not have access to the rehabilitative programs, mental health treatment, and other developmentally appropriate services that are available in the youth justice system.13

Youth charged as adults are eligible to receive longer, harsher sentences

Youth sentenced in adult courts may receive extreme sentences, such as life without parole. Following the Supreme Court’s 2005 ruling in Roper v Simmons,14 youth may not be sentenced to death. This leaves life without parole as the most extreme sentence that can be imposed on youth, which the Court has also curtailed.15

Many people in prison are serving lengthy sentences for crimes committed before turning 18, an outcome that is only possible when youth are charged as if they were adults. There are 32,359 people (in 45 states where data were available) in adult prisons for crimes committed as youth, amounting to 3.1% of the prison population in those states. Eight in 10 are youth of color.16

Incarcerating youth in adult facilities is dangerous

Youth charged as adults who are incarcerated in an adult prison or jail for any period are at an increased risk of physical and sexual abuse17 and negative mental health impacts.18

A Brief History of Automatic Charging

Even after the establishment of the first juvenile court in 1899, the United States has always allowed some youth to be charged as if they were adults.19 However, during the 1980s and 1990s, charging youth as adults took on a new scale, as most states established automatic charging provisions and others expanded laws that allow more youth to be charged in the adult system.20 This expansion of automatic charging laws was a response to the baseless and racially biased “superpredator myth,”21 which predicted an increase in youth committing violent crime.22 The myth was debunked: youth offending was on the decline even as the super-predator myth garnered media attention. By 2001, political scientist John DiIulio, who coined the term, renounced his theory.23 However, the policy implications and subsequent harm are still in place today.

What happens when a youth is charged as if they were an adult?

The outcomes of a youth automatically charged as if they were an adult vary by case and jurisdiction. After a case is filed in adult criminal court, a motion may be made to request that the case be remanded to juvenile court in a process known as “reverse waiver.” Several factors, including specific state laws, prosecutor and judicial discretion, seriousness of the offense, and prior arrests could impact the decision to waive the case back to juvenile court.24 Twenty-eight states allow reverse waivers.25

In 2014, among a broad sample of youth ages 12 to 17 charged in adult criminal courts through various transfer mechanisms, 45% resulted in an adult criminal conviction, whereas 54% resulted in a non-conviction. Non-convictions include dismissals, not guilty findings, deferred prosecutions, and cases waived back to juvenile court.26 Moreover, 70% of cases that resulted in an adult conviction came through a guilty plea – other primary methods of conviction include jury trial or bench/court trial.

Sentences for youth convicted in adult criminal court vary by type of offense.27 Across all offense types, the most common ordered sentences were court costs or restitution (32%) and probation (21%); followed by adult prison (16%) and adult jail (15%).

In 2022, 1,900 youth (under 18 years old) were held in an adult jail, and 437 were serving sentences in an adult prison.28

Automatic charging uses limited information to send youth to the adult system

We know that charging youth as adults harms youth wellbeing and community safety. Decisions to send youth to adult court should be made with careful consideration. Automatic charging is a particularly inefficient way to decide about transfers because it only considers the initial charge. A juvenile court judge’s discretion should be used based on the circumstances of the case, rather than simply basing the decision solely on the immediate offense. Juvenile court judges are trained to consider factors such as childhood trauma and adolescent brain development when making decisions regarding youth. Automatic charging sidesteps the juvenile courts’ involvement in the transfer process.

Recommendations

- End automatic charging and begin all cases involving youth under 18 in juvenile court.

- Ensure that decisions to send youth to adult court are always reviewed by a judge, ideally in juvenile court.

- Limit pathways for youth to enter the adult criminal legal system.

- Remove all youth from adult prisons and jails.

Reforms limiting or eliminating automatic charging provisions

California

In 2018, SB 1391 was signed into law, which prevents 14 and 15-year-olds charged with a crime from being tried as if they’re adults under any circumstance.29

Virginia

Virginia has a very limited list of five charges, four of them categories of murder, in which youth can be automatically charged as if they’re adults. In 2020, legislators approved SB 546, which raised the minimum age from 14 to 16 for a young person to be automatically tried as an adult for these charges. Virginia does not allow people under age 16 to start their cases in adult court under any circumstance.

In addition, six states require all of their cases involving their juvenile population to originate in juvenile court for all charges, with the juvenile court judge retaining discretion over whether the youth is waived to adult court: California, Hawaii, Kansas, Missouri, Oregon, and Texas.30

Kansas

In 2016, Kansas enacted SB 367, a comprehensive youth justice reform bill. Among other reforms, the law eliminated “extended jurisdiction juvenile prosecution,” for all offenses except the most serious felonies, such as aggravated rape and homicide. Extended jurisdiction juvenile prosecution is Kansas’s blended sentencing scheme that allows certain youth to receive both juvenile and adult sentences. The measure also raised the minimum age for adult prosecution from 12 to 14 years old.31

| 1. | Greene, T. (2025, October 21). Should youth be charged as adults in the criminal justice system? American Bar Association. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Rovner, J (2025). Youth justice by the numbers. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | Development Services Group, Inc. (2024). Youth in the adult criminal justice system. Model Program Guide. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

| 4. | Since 2019,Kentucky and Tennessee added automatic charging to their state laws, and Oregon eliminated automatic charging. Also, the U.S. Attorney’s Office automatically charges youth as adults in the District of Columbia. Rovner, J. (2025, September 16). DC youth in adult courts. The Sentencing Project. Puzzanchera, C., Sickmund, M., & Hurst H. (2022). Youth and the juvenile justice system: 2022 national report. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 5. | In 2019, judges waived 3,300 youth to adult court. Judicial waivers allow juvenile court judges, upon request from a prosecutor, to waive jurisdiction over a case and refer it to adult criminal court. Judicial waivers are typically limited by age and offense. In addition, four states – Georgia, Wisconsin, Texas, and Louisiana – still consider every 17-year-old who is arrested to be an adult and prosecute them in the adult criminal legal system. In 2019, an estimated 40,800 of those youth charged as adults were in states with age boundaries lower than 18. Puzzanchera, C., Sickmund, M., & Hurst, H. (2021). Youth younger than 18 prosecuted in criminal court: national estimate, 2019 cases. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 6. | In many jurisdictions (such as Florida), this is called “direct file,” a term that is used in other locales (such as Pennsylvania) to describe automatic charging. |

| 7. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2007). Effects on violence of laws and policies facilitating the transfer of youth from the juvenile to the adult justice system: A report on recommendations of the task force on community preventive services; Redding, R. (2008). Juvenile transfer laws: an effective deterrent to delinquency? Juvenile Justice Bulletin. |

| 8. | Maryland Governor’s Office of Crime Prevention and Policy (2024). Juveniles charged as adults (2024). |

| 9. | Alabama Juvenile Justice Take Force. (2017). Final report, p. 5. One file with author. |

| 10. | Nebraska Judicial Branch (2025). Juvenile justice system: annual report, 2024. |

| 11. | Casey, B.J., Cimmons, C., Somerville, L.H., & Baskin-Sommers, A. (2022). Making the sentencing case: psychological and neuroscientific evidence for expanding the age of youthful offenders. Annual Review of Criminology, 5:321-43. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-113250 |

| 12. | Puzzanchera, C. and Hockenberry, S. (2022) Patterns of Juvenile Court Referrals of Youth Born in 2000. Juvenile Justice Statistics: National Report Series Bulletin. |

| 13. | Development Services Group, Inc. (2024). Youth in the adult criminal justice system, pp. 14-15,18. Model Program Guide. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention |

| 14. | Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005). |

| 15. | Rovner, J. (2023). Juvenile life without parole. The Sentencing Project |

| 16. | Bryer, S. (2023). Crimes against humanity — The mass incarceration of children in the United States. Human Rights for Kids. |

| 17. | National Prison Rape Elimination Commission (2009), National Prison Rape Elimination Commission Report. |

| 18. | Development Services Group, Inc. (2024). Youth in the adult criminal justice system. Model Program Guide. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

| 19. | Feld, B. C. (1987). The juvenile court meets the principle of the offense: Legislative changes in juvenile waiver statutes. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology, 78(3), 471–533. https://doi.org/10.2307/1143567. |

| 20. | Torbet, P., et al. (1996). State responses to serious and violent juvenile crime. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. |

| 21. | Bogert, C., & Hancock, L. (2020, November 20). Analysis: How the media created a ‘super-predator’ myth that harmed a generation of Black youth. NBC News. |

| 22. | DiIulio, J. (1995.) The coming of the super-predators. Weekly Standard. |

| 23. | Becker, E. (2001, February 9). As ex-theorist on young ‘superpredators,’ Bush aide has regrets. The New York Times. |

| 24. | Strong, S. (2025). Juveniles charged in adult criminal courts, 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 25. | Puzzanchera, C., Sickmund, M., & Hurst H. (2022). Youth and the juvenile justice system: 2022 national report. pp. 95-96. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 26. | Strong, S. (2025). Juveniles charged in adult criminal courts, 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 27. | Strong, S. (2025). Juveniles charged in adult criminal courts, 2014. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 28. | Carson, E.A. & Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2022 – Statistical Tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, plus prior editions; Zeng, Z. Carson, E.A., & Kluckow, R. (2023). Just the Stats; Juveniles Incarcerated in U.S. Adult Jails and Prisons, 2002–2021; Zeng, Z. (2023). Jail Inmates in 2022 – Statistical Tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, plus prior editions. |

| 29. | SB 1391. Chapter 1012, Statutes of 2018 https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180SB1391 |

| 30. | Puzzanchera, C., Sickmund, M., & Hurst H. (2022). Youth and the juvenile justice system: 2022 national report. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 31. | Pew Charitable Trusts. (2017). Kansas’ 2016 juvenile justice reform (Issue Brief). |