Virginia Should Restore Voting Rights to Over a Quarter Million Citizens

Virginia has the fourth-highest disenfranchised population in the nation, behind only Florida, Texas, and Tennessee.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy

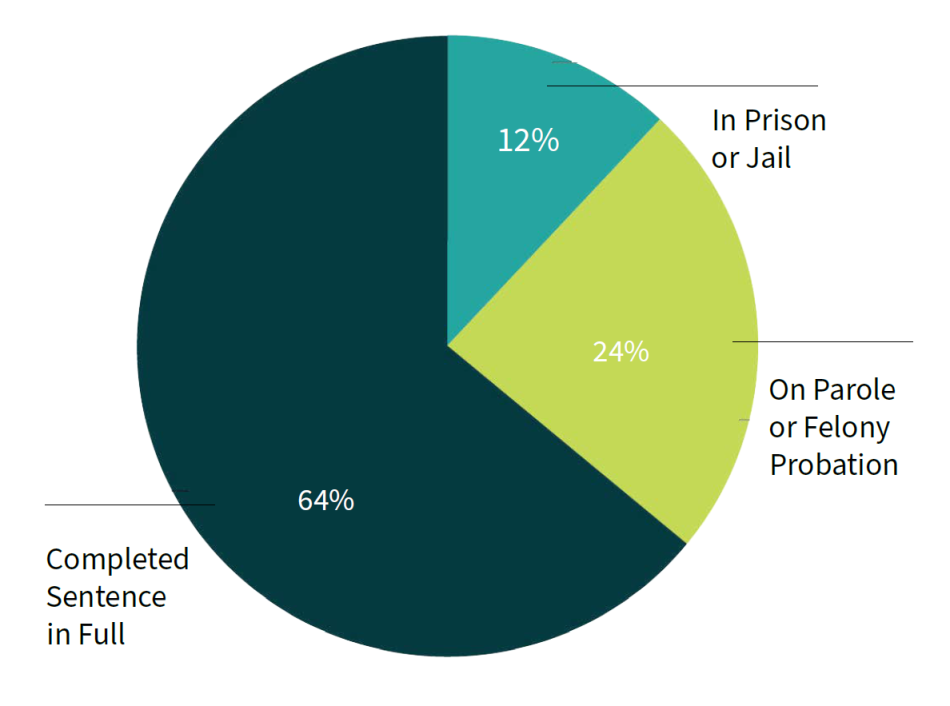

More than 260,000 citizens are banned from voting in Virginia due to a felony-level conviction.1 Virginia has the fourth-highest disenfranchised population in the nation, behind only Florida, Texas, and Tennessee. The overwhelming majority of disenfranchised Virginians are not incarcerated but are living in the community. Virginia’s ban on voting for people who are no longer incarcerated affects over 230,000 citizens.

People Denied the Right to Vote Due to a Felony Conviction in Virginia, 2024

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

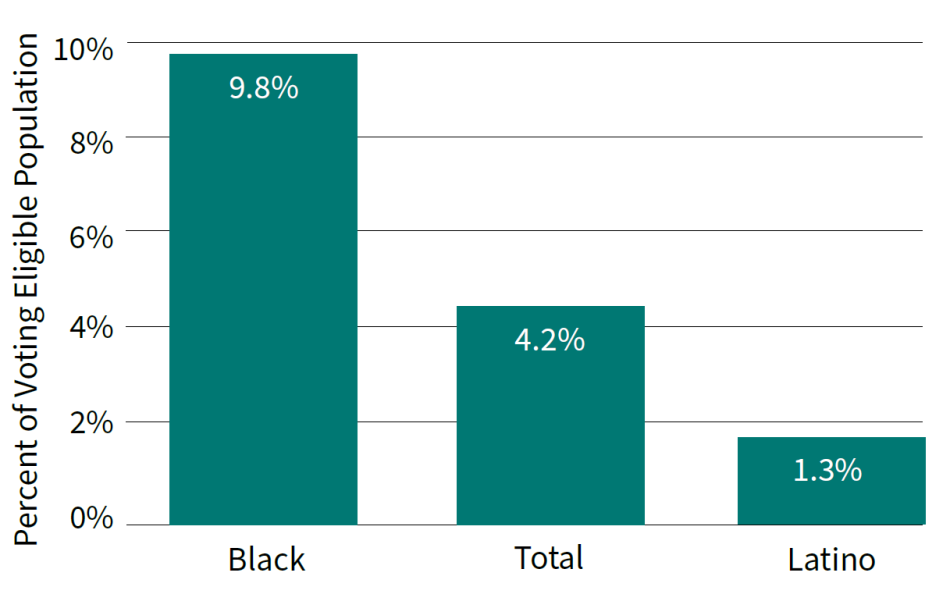

Virginia’s voting ban on its citizens with a felony conviction causes racial injustice at the ballot box. Roughly one out of every 10 Black voting-eligible Virginians is banned from voting due to a felony-level conviction.2 Black voting-eligible Virginians are 3.5 times as likely to be disenfranchised as non-Black Virginians.3 This dilutes the voice of Black Virginians in the state’s democratic process.

Voter Exclusion in Virginia by Race and Ethnicity, 2024

Source: Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

The law restricting voting for people who have a felony conviction undermines Virginia’s democracy and its electoral system. To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Virginia should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC, and extend voting rights to all citizens.

Expanding Voting Rights in Virginia is a Racial Justice Issue

From 1723 up until the end of the Civil War, Black Virginians were expressly forbidden from voting.4 The passage of the Underwood Constitution during Reconstruction in 1870 codified the right to vote for all men aged 21 and over, regardless of race. However, racist backlash in the subsequent decades heralded the arrival of Jim Crow laws, which targeted Black Virginians and anyone convicted of a felony for disenfranchisement.5

Contemporarily, felony disenfranchisement inflicts unequal weight on Black Virginians, largely due to disparities in the state’s criminal legal system. Despite comprising 18% of the total population in Virginia, Black people make up almost 52% of those in prison.6 Black Virginians are incarcerated at almost four times the rate of white Virginians. Such disparities in incarceration go beyond any differences in criminal offending and reflect differential practices throughout Virginia’s criminal legal system. The following examples illustrate the disparate effects of these practices on people of color in Virginia:

- Mandatory minimums: A 2020 research report from the Virginia Department of Corrections revealed that Black people in Virginia prisons are more likely to have mandatory minimum sentences than white people: 41% compared to 26%.7 Furthermore, for those with drug sales as their most serious offense, the average total imposed sentence was 42% longer for Black people than white people with mandatory minimums.8 For people with larceny/fraud as their most serious offense, the average total imposed sentence was 14% longer for Black people than for white people with mandatory minimums.9

- Drug-related offenses: Black Virginians were five times as likely as white Virginians to be arrested for marijuana possession, according to the Virginia Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, who analyzed arrest and court data from 2015 to 2019.10 When Black Virginians were arrested, their arrests also had a higher likelihood of turning into a court proceeding compared to arrests involving white Virginians.11 In 2022, The Washington Post reported that even after the legalization of marijuana in the state, Black Virginians remained more likely than white Virginians to be arrested for marijuana-related offenses, accounting for 60% of cases before the state’s district and circuit courts.12 This is in spite of evidence indicating that nationally, marijuana usage does not substantially differ across racial groups.13

- Traffic stops: Black drivers in Virginia were more likely to be stopped than white drivers, according to a 2023 analysis of traffic stop data by the Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services.14 The Department found that although 19% of Virginia’s driving-age population was Black, 30% of drivers stopped were Black. This is in spite of 2021 legislation limiting police power to only conduct traffic stops for serious offenses such as speeding or reckless driving, instead of minor violations such as defective taillights or objects dangling in the rearview mirror.15

- Arrest rates: In Fairfax County, Virginia, the ACLU People Power Fairfax found that the arrest rate for Black people increased year-on-year.16 In 2016, the arrest rate for Black people in Fairfax County was 2.5 times their proportion in the general population; in 2019, this jumped to 4 times the proportion.17 Latino people were also disproportionately arrested at twice the rate of their population on average.18

Virginia should safeguard democratic rights and not allow a racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.19 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful reentry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”20 Research also suggests that having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states that continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states that had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.21

Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon reentry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons or jails or who are under community supervision, as well as citizens who have completed their entire sentence, supports successful reentry and strengthens civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of a felony conviction, Virginia can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Virginia Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

The recent history of rights restoration efforts in Virginia has been marked by dramatic and unpredictable changes, depending on each new gubernatorial administration. These inconsistencies have fostered uncertainty and challenges for many Virginians simply seeking to express their political rights. In the early 2000s, Governor Mark Warner introduced reforms relating to the rights restoration process and restored voting rights to 3,500 Virginians.22 This momentum was carried forward in the 2010s by Governor Bob McDonnell. His 2013 executive order restored voting rights to those who had completed sentences for non-violent convictions and had paid all financial obligations.23 Under Governor McDonnell’s administration, almost 7,000 Virginians regained the right to vote.24 In 2016, Governor Terry McAuliffe issued an executive order to automatically restore the right to vote to those with felony convictions who had completed their sentences.25 This order was struck down that same year by the Virginia Supreme Court in Howell vs. McAuliffe. The Court stated that the Governor had unconstitutionally exceeded his powers, ordering rights restoration to be applied on an individual basis.26 Governor McAuliffe ultimately restored voting rights to over 173,000 Virginians.27

In 2021, Governor Ralph Northam announced new executive action to restore the right to vote to those with felony convictions who were no longer in prison or jail.28 Governor Northam’s effort restored voting rights to over 126,000 Virginians.29 Then, in 2023, Governor Glenn Youngkin reversed this course of action, only restoring voting rights through petitions submitted by individuals and assessed on a case-by-case basis, resulting in a significant decline in civil rights restorations.30 Under Governor Youngkin’s administration, voting rights restorations decreased year-on-year between 2022 and 2025.31 As of 2025, those who have completed their sentence for a felony-level conviction may have their voting rights restored by a successful petition to the Governor of Virginia. This back-and-forth in voting rights restoration processes creates an unpredictable and volatile voting rights landscape for justice-impacted Virginians.

To formalize and guarantee voting rights for justice-impacted people, Senator Mamie Locke and Delegate Elizabeth Bennett Parker proposed a Joint Resolution (SJ248; HJ2) in 2025.32 This constitutional amendment would provide automatic restoration of voting rights upon release from incarceration.33 The amendment passed both the House and Senate in January 2026.34 If approved by a simple majority of voters, the amendment will enter Virginia’s constitution. In January 2026, a federal judge ruled in King v. Youngkin, that the state’s Constitution violated federal law when Virginia’s representatives were readmitted to Congress after the Civil War in the Virginia Readmission Act, on the condition that Virginia could not further deprive citizens of the right to vote except for a set of felonies that were common law in 1870. The ruling paves the way for many Virginians, convicted of modern offenses like drug-related violations, to have their voting rights restored.35 John Campbell III, a Black justice-impacted Virginian whose voting rights were restored in 2023, described voting to RadioIQ: “I feel like somebody…I feel it’s power. I got a shot. Something might change…At last I got my rights back before I die…And I want everybody to know and see.”36

Continuing to exclude Virginians with a felony conviction from voting betrays the state’s own constitutional provision that “all power is vested in, and consequently derived from, the people.”37 Virginia should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by restoring the right to vote for its entire voting-eligible population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Voting eligible adults are defined as individuals who are at least 18 years old and a U.S. citizen. Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 4. | Bennett, J. (2020, September 9). “On account of race”: Disenfranchisement of Black voters in Virginia. The Uncommon Wealth: Voices from the Library of Virginia. |

| 5. | The 1902 constitution again disenfranchised Black people following the introduction of Jim Crow laws; Tran, P. (2020, February 28). The racist roots of felony disenfranchisement in Virginia. ACLU of Virginia. |

| 6. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; U.S. Census Bureau. (2023). American Community Survey, ACS 5-year estimates detailed tables – table B03002. U.S. Census Bureau. |

| 7. | Va. Department of Corrections Statistical Analysis & Forecast Unit. (2020). Disparities in sentencing among inmates with mandatory minimum sentences. Virginia Department of Corrections. |

| 8. | Va. Department of Corrections Statistical Analysis & Forecast Unit. (2020). Disparities in sentencing among inmates with mandatory minimum sentences. Virginia Department of Corrections. |

| 9. | Va. Department of Corrections Statistical Analysis & Forecast Unit. (2020). Disparities in sentencing among inmates with mandatory minimum sentences. Virginia Department of Corrections. |

| 10. | Harrison, A. (2021, March 19). Virginia’s drug law enforcement disproportionately impacts Black citizens. Reason Foundation. |

| 11. | Harrison, A. (2021, March 19). Virginia’s drug law enforcement disproportionately impacts Black citizens. Reason Foundation. |

| 12. | Elwood, K., & Harden, J. D. (2022, October 16). After Virginia legalized pot, majority of defendants are still Black. The Washington Post. |

| 13. | Edwards, E., Greytak, E., Madubuonwu, B., Sanchez, T., Beiers, S., Resing, C., Fernandez, P., & Galai, S. (2020). A tale of two countries: Racially targeted arrests in the era of marijuana reform. ACLU. |

| 14. | Miller, J., & Johnson, S. (2023). Report on analysis of traffic stop data collected under Virginia’s Community Policing Act. Virginia Department of Criminal Justice Services. See also Paviour, B. (2023, August 3). Black drivers in Virginia still more likely to be stopped as charges drop. VPM Media Corporation. |

| 15. | Ghandnoosh, N., & Barry, C. (2023). One in five: Disparities in crime and policing. The Sentencing Project. |

| 16. | The “ACLU People Power Fairfax” is a grassroots organization in Fairfax, Virginia advocating for equal justice for all and the end of voluntary cooperation and information sharing with ICE. The platform was founded by the American Civil Liberties Union, but each group is independent. |

| 17. | ACLU People Power Fairfax. (2020). Disparity in FCPD arrests. ACLU of Virginia. |

| 18. | ACLU People Power Fairfax. (2020). Disparity in FCPD arrests. ACLU of Virginia. |

| 19. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 20. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 21. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 22. | Porter, N. D., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 23. | Israel, J. (2013, May 29). Virginia governor automatically restores voting rights to nonviolent felons. ThinkProgress. |

| 24. | Porter, N. D., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 25. | Equal Justice Initiative. (2016, April 22). Virginia governor restores voting rights to more than 200,000 formerly incarcerated people. Equal Justice Initiative. |

| 26. | ACLU of Virginia. (2016). Court cases: Howell v. McAuliffe. ACLU of Virginia. |

| 27. | Associated Press. (2018, January 10). Outgoing Va. gov. McAuliffe says rights restoration his proudest achievement. The Associated Press. |

| 28. | Northam, R. (2021, March 16). Governor Northam restores civil rights to over 69,000 Virginians, reforms restoration of rights process. Office of the Governor; Equal Justice Initiative. (2021, March 17). Virginia governor restores voting rights to over 69,000 formerly incarcerated citizens. Equal Justice Initiative. |

| 29. | Schneider, G. S., & Vozzella, L. (2022, January 14). Northam issues pardons in flurry of actions before leaving office. Washington Post. |

| 30. | Paviour, B. (2023, April 13). Gov. Youngkin slows voting rights restorations in Virginia, bucking a trend. NPR. |

| 31. | Mirshahi, D. (2025, February 27). Voting rights restorations drop for 3rd year in a row under Youngkin. VPM. |

| 32. | VA Sen. (2025). Proposing an amendment to Section 1 of Article II of the Constitution of Virginia, relating to qualifications of voters; right to vote; persons not entitled to vote [SJ 248, 2025 Sess.]. Senate of Virginia. |

| 33. | VA Sen. (2025). Proposing an amendment to Section 1 of Article II of the Constitution of Virginia, relating to qualifications of voters; right to vote; persons not entitled to vote [SJ 248, 2025 Sess.]. Senate of Virginia. |

| 34. | Burness, A. (2026, January 16). “It’s time”: Virginia lawmakers ask voters to repeal Jim Crow-era lifetime ban on voting. Bolts. |

| 35. | King v. Youngkin, No. 3:23-cv-00352, slip op. (E.D. Va. June 26, 2023). |

| 36. | Noe-Payne, M. (2023, December 1). Branded: The fight to restore voting rights. RadioIQ. |

| 37. |