Expanding the Vote: State Felony Disenfranchisement Reform, 1997-2023

Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people living with felony convictions. As a result, over 2 million Americans have regained the right to vote.

Related to: Voting Rights

Overview

Voting eligibility and a person’s involvement in the criminal legal system have a historical but unnatural association in the United States. Some state laws dating back over 100 years, and motivated by racist ideology, permanently ban people convicted of a felony from voting, and almost all states have long prevented voting by people in prison. Over the last 50 years the country’s investment in mass incarceration not only staggeringly increased the prison population and the community of people with a criminal record but increased the number of people banned from voting due to a felony conviction.1 As a result, over 4.6 million Americans with a felony conviction were disenfranchised as of 2022,2 disproportionately impacting Black and Latinx residents.

Despite the stark consequences of mass incarceration and voter disenfranchisement,3 the advocacy of incarcerated and formerly incarcerated activists, organizers, legislative champions, and others have successfully fought to pass reforms to expand voting rights to justice-impacted individuals. These changes, both administrative and statutory in recent decades, coupled by recent modest declines in the population of incarcerated people and those under community supervision reduced the total number of people disenfranchised by 24% since reaching its peak in 2016.4

Understanding the origins of this progress to restore voting rights is beneficial for democracy and justice. This report provides a state-by-state accounting of the changes to voting rights for people with felony convictions and measures its impact.5 Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people living with felony convictions or amended policies to guarantee ballot access. These reforms were achieved through various mechanisms, including legislative reform, executive action, and ballot measures.

The reforms include:

- restoration of voting rights to persons in prison in Washington, DC;

- expansion of voting rights to some or all persons on felony probation or parole in 12 states; and

- increased accessibility for persons seeking rights restoration in 14 states.

Over 2 million Americans have regained the right to vote since 1997. These changes to expand and guarantee voting rights demonstrate national momentum to reform the nation’s restrictive and racially discriminatory voting laws.

| State | Change | # People Impacted |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama |

Streamlined restoration process (2003); established list of felony offenses that result in loss of voting rights (2017) |

83,376 |

| California |

Restored voting rights to people on community supervision under Realignment (2014); restored voting rights to people convicted of a felony offense housed in jail, but not in prison (2016); expanded voting rights to persons on parole (2020). |

145,000 |

| Colorado |

Authorized persons on parole to pre-register to vote prior to completing their sentence (2018); expanded voting rights to persons on parole (2019). |

11,500 |

| Connecticut |

Restored voting rights to persons on felony probation (2001); repealed requirement to present proof of restoration in order to register (2006); expanded voting rights to persons on parole (2021). |

37,000 |

| Delaware |

Repealed lifetime disenfranchisement and replaced with five-year waiting period for most offenses (2000); repealed five-year waiting period for most offenses (2016). |

6,989 |

| District of Columbia |

Expanded voting rights to incarcerated persons with a felony conviction (2020). |

2,400 |

| Florida |

Simplified clemency process (2004, 2007); adopted requirement for county jail officials to assist with restoration (2006); reversed modification in clemency process (2011); ended lifetime disenfranchisement. |

238,722 |

| Georgia |

The Secretary of State clarified that anyone who has completed their sentence, even if they owe outstanding monetary debt, can vote (2020). |

40,679 |

| Hawaii |

Codified data sharing procedures for removal and restoration process (2006). |

- |

| Iowa |

Restored voting rights post-sentence via executive order (2005); rescinded executive order (2011); simplified application process (2016); restored voting rights post-sentence via executive order (2020). |

120,776 |

| Kentucky |

Simplified restoration process (2001, 2008); restricted restoration process (2004, amended in 2008); restored voting rights post-sentence for nonviolent felony convictions via executive order (2015); rescinded executive order (2015); restored voting rights post-sentence via executive order to persons with non-violent offenses (2019). |

150,559 |

| Louisiana |

Established notification of rights restoration process (2008); authorized voting for residents who have not been incarcerated for five years including those on probation or parole (2017). |

43,000 |

| Maryland |

Repealed lifetime disenfranchisement (2002 & 2007); restored voting rights to persons on felony probation and parole (2016). |

92,000 |

| Minnesota |

Restored voting rights to persons on felony probation and parole (2023). |

46,000 |

| Nebraska |

Repealed lifetime disenfranchisement, replaced with two-year waiting period (2005). |

50,276 |

| Nevada |

Repealed five-year waiting period to restore rights (2001), restored voting rights to persons convicted of first-time nonviolent offense (2003), restored voting rights to people dishonorably discharged from felony probation or parole, allowed people convicted of category B offenses to have their rights restored after two-year waiting period (2017); restored voting rights to persons on felony probation or parole (2019). |

77,000 |

| New Jersey |

Established procedures requiring state criminal justice agencies to notify persons of their voting rights when released (2010); expanded voting rights to people on felony probation and parole (2019). |

80,000 |

| New Mexico |

Repealed lifetime disenfranchisement (2001); streamlined restoration process and established notification system (2005); expanded voting rights to people on felony probation and parole (2023). |

80,000 |

| New York |

Required criminal justice agencies to provide voting rights information to persons who are again eligible to vote after a felony conviction (2010); restored voting rights to persons on parole via executive order (2018); legislature codified voting rights restoration for persons on parole (2021). |

35,000 |

| North Carolina |

Established process to notify people of their voting rights (2007) |

- |

| Rhode Island |

Restored voting rights to persons on probation and parole (2006) |

17,000 |

| Tennessee |

Streamlined restoration process for most persons upon completion of sentence (2006) |

5,449 |

| Texas |

Repealed two-year waiting period after completion of sentence (1997) |

317,000 |

| Utah |

Clarified state law pertaining to federal and out-of-state convictions (2006) |

- |

| Virginia | Established notification of rights and restoration process (2000); streamlined restoration process (2002); decreased waiting period for nonviolent offenses from three years to two years and established a 60-day deadline to process voting rights restoration applications (2010); eliminated waiting period and application for nonviolent offenses (2013); restored voting rights post-sentence via executive order (2016); expanded rights restoration to post-incarceration via executive order (2020); scaled back rights restoration provision to post-sentence (2023). | 317,300 |

| Washington | Restored voting rights for citizens who exit the criminal justice system but still have outstanding financial obligations (2009); restored voting rights after incarceration (2021). | 20,000 |

| Wyoming | Allowed persons convicted of first-time nonviolent offenses to apply for rights restoration after five year waiting period (2003); removed application process and waiting period for people convicted of first-time nonviolent offenses (2015); automatically restored voting rights to people convicted of all nonviolent offenses (2017) | 4,282 |

| Total | 2,021,308 |

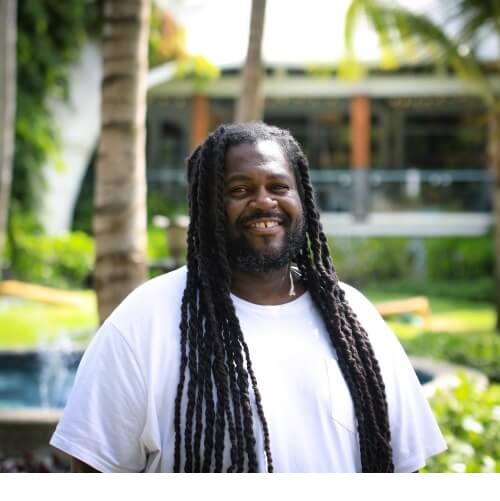

Formerly incarcerated folks are closest to the social issues and we should have a say on how the government addresses our needs. With our rights restored, we can all vote to end 50 years of mass incarceration and live in a society that is ran on compassion and understanding. We are tired of out of touch elected officials.

State Reforms

Alabama: Voting Rights Restored to 83,376 People, 2004-2021

Alabama prohibits voting by people sentenced to prison or living under community supervision on felony probation and parole, and after sentence completion of certain offenses.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Alabama Disenfranchised Population | 318,681 | 8.6% |

| Black | 143,557 | 14.7% |

| Latinx | 3,775 | 4.9% |

In 2003, lawmakers passed Act 2003-415 to streamline the application process for obtaining an eligibility certificate for people convicted of a nonviolent offense who completed the term of their sentence. Specifically, it required the state to issue an explanation of denial within 45 days of application or an eligibility certificate within 50 days of the application. The number of individuals achieving voting rights restoration increased by 79% following the first year of the reform’s enactment. Between 2004 and 2021, 23,376 people had their voting rights restored through the timely issuance of eligibility certificates.6

Alabama’s Constitution bans voting rights for residents convicted of felonies classified as involving “moral turpitude.” Before 2017, the state never specified which offenses disqualified a resident from voting due to this classification. The lack of a statutory definition resulted in a disparate practice from county to county, giving local election officials the discretion to determine which convictions banned residents from voting. In 2017, Governor Kay Ivey signed the Definition of Moral Turpitude Act, which specified for the first time a list of 47 disqualifying offenses that resulted in a denial of voting rights. At the time of passage, Alabama officials estimated 60,000 residents would have their voting rights reinstated automatically because they had been denied based on offenses not on the list.7

California: Voting Rights Restored to 145,000, 2011-2020

In California, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| California Disenfranchised Population | 97,328 | 0.4% |

| Black | 28,578 | 1.7% |

| Latinx | 43,435 | 0.6% |

California’s 2011 Realignment policy diverted many individuals convicted of non-violent felonies from incarceration in state prisons to local jails or community supervision where individuals would report to probation officers. At the time, California law allowed people on felony probation, but not parole or prison, to vote. In 2011, Secretary of State Debra Bowen instructed county election officials to extend the voting ban to people with felony convictions who were moved to jails or community supervision under Realignment. Civil rights groups sued the state on behalf of citizens on community supervision, arguing that because these individuals now report to county probation officers instead of state parole officers, they are therefore on probation and should be allowed to vote. In 2014, a superior court ruled Bowen’s application of the Realignment Act was unconstitutional, asserting the intention of the law was to “introduce [formerly incarcerated persons] into the community, which is consistent with restoring their right to vote.” The state appealed the ruling. In 2015, Alex Padilla, Bowen’s successor, reversed her policy and dropped the case. Padilla’s action expanded voting rights to 45,000 people on post-release community supervision.8

Assembly Bill 2466, signed by Governor Jerry Brown in 2016, further expanded voting rights under the Realignment Act. The measure authorized voting rights for an estimated 50,000 people serving felony sentences in county jails.9

In 2020, 59% of California voters approved Proposition 17, amending the state Constitution to restore voting rights to individuals on parole.10 The measure restored the vote to approximately 50,000 people.11

Colorado: Restoration of Voting Rights to 11,500 People, 2019

In Colorado, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Colorado Disenfranchised Population | 17,455 | 0.4% |

| Black | 3,272 | 2.0% |

| Latinx | 5,268 | 0.8% |

Prior to 2019, people on parole were required to complete their sentence before regaining the right to vote. In an effort to combat misinformation around voting with a felony conviction, Colorado lawmakers passed legislation in 2018 authorizing people on parole to pre-register to vote prior to completing their sentence. The legislation required parole officers to inform individuals on parole of their voting rights and required the state’s department of corrections to provide the secretary of state with a monthly report of individuals released from parole so their voting status could be updated.12 A year later, House Bill 1266 expanded voting rights to nearly 11,500 residents on parole.13

Connecticut: Voting Rights Restored to 37,000 People, 2001-2021

In Connecticut, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Connecticut Disenfranchised Population | 6,892 | 0.3% |

| Black | 3,029 | 1.2% |

| Latinx | 1,919 | 0.6% |

Connecticut lawmakers expanded voting rights to more than 33,000 people on felony probation in 2001.14 However, people seeking the right to vote were required to provide “written or satisfactory proof” of voter eligibility. In 2006, state policymakers repealed that requirement, removing potential complications that may arise in securing such proof and increasing the likelihood that eligible residents would take advantage of their right to vote.14

In 2021, Connecticut lawmakers expanded voting rights to people on parole living in their community.16 This change reinstated voting rights to an estimated 4,000 Connecticut residents.17

Restoring the right to vote is smart policy. It enables people who are incarcerated to feel connected to their communities, especially as they re-enter society, and therefore reduces the likelihood of them taking part in criminal activity and returning to prison. After all, if I’m an active voter then I’m an active voice in my community. But all that is held up if I’m not given the right to vote.

Delaware: Voting Rights Restored to 6,989 People, 2000-2013

Delaware disenfranchises individuals with felony convictions in prison, on felony probation or parole, and after completion of sentence for certain felony offenses.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Delaware Disenfranchised Population | 7,721 | 1.1% |

| Black | 4,016 | 2.6% |

| Latinx | 423 | 1.1% |

In 2000, Delaware lawmakers amended the state’s constitution to repeal lifetime disenfranchisement and allow most residents convicted of a felony offense to apply to the Board of Elections for their voting rights five years after the completion of their sentence. The reform continued to ban voting rights for people with certain convictions (murder or crimes of a sexual nature) unless they were pardoned. Voting rights were restored to an estimated 6,400 individuals, or about one-third of the state’s disenfranchised population at the time.14

In 2013, state policymakers adopted the Hazel D. Plant Voter Restoration Act,19 which removed the five-year waiting period and automatically restored voting rights to eligible persons who completed their sentence. Those convicted of a disqualifying felony offense are still permanently disenfranchised. Delaware reported 589 pardons and commutations for 2020 through midyear 2022.4

District of Columbia: Voting Rights Restored to 2,400 People, 2020

Residents with felony convictions in the District of Columbia never lose their right to vote.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| DC Disenfranchised Population | 0 | 0% |

| Black | 0 | 0% |

| Latinx | 0 | 0% |

In 2020, Washington, DC officials authorized universal suffrage through the passage of the Restore the Vote Amendment.21 The change restored voting rights for incarcerated citizens with a felony conviction. The District joined Maine, Vermont, and Puerto Rico in the elimination of felony disenfranchisement.

At the time of passage, the DC Board of Elections reported sending 2,400 voter registration forms to incarcerated residents in jail and prison.22

Florida: Voting Rights Restored to 238,722, 2004-2021

Florida authorizes voting for most citizens who have completed their sentence and paid their fines and fees. Persons convicted of murder and crimes of a sexual nature are disqualified from voting for life unless they receive clemency from the governor.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Florida Disenfranchised Population | 1,150,944 | 7.5% |

| Black | 291,811 | 12.8% |

| Latinx | 106,709 | 3.4% |

Florida officials and voters have addressed one of the nation’s most restrictive disenfranchisement laws through a series of policy changes. In 2004, then-Governor Jeb Bush amended the Rules of Executive Clemency to expedite the voter restoration process, alleviating a backlog of tens of thousands of rights restoration applications.14 Before Gov. Bush’s rule change, individuals were required to attend an in-person clemency hearing. The change limited the requirement for an in-person hearing as long as they were not convicted of a violent crime and had remained arrest-free for five years. Individuals convicted of all other offense types were required to complete a 15-year arrest-free period before applying to have their rights restored. Gov. Bush restored voting rights to 75,000 people during his two terms in office.24

In 2006, Florida lawmakers passed a bill requiring correctional facilities to provide people in prison with rights restoration application information at least two weeks prior to their release date. This change was in response to the difficulties presented by Florida’s complex and confusing restoration process.14

In 2007, Governor Charlie Crist and the Board of Executive Clemency approved a new rule change, automatically restoring voting rights for individuals convicted of certain, mostly nonviolent offenses. Residents convicted of more serious offenses, excluding some violent crimes and crimes of a sexual nature, became eligible to have their voting rights restored without a clemency hearing. Individuals convicted of murder or crimes of a sexual nature are still required to wait 15 years after sentence completion (during which time they must remain arrest-free) to apply without a hearing or to petition the Board directly for a review and in-person hearing. During Crist’s administration, voting rights were restored to more than 150,000 people.14

During Governor Rick Scott’s administration, the 2007 clemency rules were amended to require the clemency board to review all rights restoration applications. The 2011 change also added additional paperwork for each case, regardless of offense type. As a result, rights restoration applications declined by nearly 95%.27

In 2018, Florida voters expanded voting rights to as many as 1.4 million Floridians with a felony conviction by approving Amendment 4. The change provided for the automatic reinstatement of voting rights for justice-involved residents with eligible felony conviction histories once they completed their prison, felony probation, or parole sentence. Persons convicted of homicide and crimes of a sexual nature were excluded from the measure. In 2019, Florida lawmakers passed and Governor Ron DeSantis signed Senate Bill 7066, restricting the voting rights of people who had not paid court-ordered monetary sanctions, and effectively re-disenfranchising the majority of those whose rights Amendment 4 had restored.28

From 2016 through 2020, 3,250 Floridians had their voting rights restored post-sentence by state officials.29 In fiscal years 2020 and 2021, the Florida Commission on Offender Review reported that 4,244 and 6,278 rights restoration applications were respectively approved.4 As of 2022, an estimated 934,500 Floridians who completed their sentences remained disenfranchised.4

Georgia: Voting Rights Restored to 40,679 People, Years 2020-2023

In Georgia, people can vote following the completion of their prison, felony probation, or parole sentence.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Georgia Disenfranchised Population | 234,410 | 3.1% |

| Black | 124,858 | 5.2% |

| Latinx | 7,467 | 2.0% |

The Georgia Secretary of State’s office clarified in 2020 that anyone who has completed their sentence, even if they carry outstanding monetary debt, can vote.32 According to the Georgia Secretary of State’s Office, fines that were a condition of probation are automatically cancelled upon completion of probation.4 Reported estimates suggest that 40,679 justice-impacted residents in Georgia became eligible to register to vote following the Secretary of State’s guidance.34

Hawaii: No Estimate Available

Hawaii restores voting rights to individuals upon release from prison.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Hawaii Disenfranchised Population | 3,007 | 0.3% |

| Black | 134 | 0.6% |

| Latinx | 71 | 0.1% |

State officials passed legislation in 2006 to guarantee ballot access for justice-impacted voters by improving information sharing. Before the policy change, many people released from prison were incorrectly coded or were not included in the eligible voter database. To address this, Hawaii lawmakers required the clerk of the court to transmit an individual’s name, date of birth, address, and social security number to the person’s county within 20 days of release.14

Iowa: Voting Rights Restored to 120,776 People, 2005-2020

Iowa disenfranchises all individuals with felony convictions for life unless they receive clemency from the governor.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Iowa Disenfranchised Population | 30,130 | 1.3% |

| Black | 6,310 | 9.5% |

| Latinx | 2,507 | 3.0% |

Before 2005, Iowa imposed a lifetime voting ban on anyone convicted of an “infamous crime.” The only mechanism in place to restore voting rights was a gubernatorial pardon. In 2005, Governor Tom Vilsack issued Executive Order 42, which immediately restored voting rights to all persons in Iowa who completed their sentence and made the restoration process automatic for new persons completing their sentence.14 The order restored voting rights to an estimated 100,000 people.37

Shortly after taking office in 2011, Governor Terry Branstad reversed Gov. Vilsack’s order, reverting the restoration process back to a case-by-case basis. During 2016, Gov. Branstad simplified the rights restoration application, reducing the number of questions in half and removing several burdensome requirements.38

In 2020, Governor Kim Reynolds issued an executive order restoring voting rights to 20,000 Iowans who completed their felony sentences.39 The measure did not include people convicted of homicide. As well, the state can impose special sentences ranging in length from 10 years to life imprisonment for certain crimes of a sexual nature.40 According to Iowa’s Secretary of State’s office, 4,127 Iowans whose registration had been canceled prior to the 2020 executive order re-registered following Gov. Reynold’s action. Of those registered voters, 3,179 participated in the November 2020 general election.41 The order took effect in January 2020, and Iowa officials reported an additional 776 restorations of voting rights by August 2020.4

Kentucky: Voting Rights Restored to 189,949 People, 2004-2023

Kentucky disenfranchises all individuals with felony convictions for life unless they secure clemency from the governor.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Kentucky Disenfranchised Population | 152,727 | 4.5% |

| Black | 29,533 | 11.5% |

| Latinx | 2,516 | 4.1% |

Kentucky, like Florida, Iowa, Tennessee and Virginia, maintains one of the most restrictive voting bans for people with felony convictions in the country. In 2001, Kentucky lawmakers passed legislation to simplify the process of applying to the governor for voting rights restoration. The law required the Department of Corrections to inform individuals of their right to apply to the governor to have their voting rights restored. In addition, the law required the department to collect information regarding all eligible citizens who have inquired about having their voting rights restored and to submit that list to the governor’s office.

In 2004, Governor Ernie Fletcher issued an executive order that reversed some of the previous progress made to ease the rights restoration process. In addition to supplying three personal reference letters, the policy change required all applicants to submit a formal letter explaining why they believed their voting rights should be restored. Subsequently, the number of individuals receiving their voting rights declined under the Fletcher administration.14 Governor Steve Beshear repealed the policy in March 2008 with the elimination of the filing fee requirement, personal statement, and reference letters. Between 2008 and 2015, approximately 10,500 people had their voting rights restored.14 He also issued an executive order automatically restoring voting rights to over 100,000 people with nonviolent felony convictions who completed their sentences in November 2015, but Governor Matt Bevin reversed the executive order a month later.45 According to his administration, Gov. Bevin issued almost 1,000 restorations of civil rights.46

As of 2023, an executive order issued by Governor Andy Beshear in 2019 resulted in more than 178,390 persons who completed sentences for nonviolent offenses regaining their voting rights.47 Kentucky officials also reported 59 restorations among those who were not otherwise eligible for restoration under the executive order.4

Louisiana: Voting Rights Restored to 43,000 People, 2018

Louisiana restricts voting rights for people in prison and individuals with felony convictions who have been incarcerated within the last five years.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Louisiana Disenfranchised Population | 52,073 | 1.5% |

| Black | 32,865 | 3.0% |

| Latinx | 213 | 0.2% |

In 2008, the state legislature passed a bill requiring the Department of Public Safety and Corrections to inform individuals who have completed their sentence of their right to vote.14

In 2018, House Bill 265 was enacted following Governor John Bel Edwards’s signing, restoring voting rights to anyone with a felony conviction who has not been incarcerated within the last five years, including those completing their sentencing on felony probation or parole.50 The measure excluded residents with election fraud or other election-related offense convictions. Estimates indicated the legislation would expand voting rights to 40,000 people completing their sentence on felony probation and 3,000 completing their sentence on parole.51

Maryland: Voting Rights Restored to 92,000 People, 2002-2016

In Maryland, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Maryland Disenfranchised Population | 16,587 | 0.4% |

| Black | 11,678 | 0.9% |

| Latinx | 771 | 0.3% |

Maryland experienced several changes in felony disenfranchisement over the last two decades. Before 2002, persons convicted of a first-time felony offense regained their voting rights after completion of their sentence, but anyone with two or more convictions was banned from voting for life. In 2002, Maryland lawmakers reformed the restoration process for persons convicted of two or more nonviolent offenses. That change authorized automatic voter eligibility for individuals with a second nonviolent conviction three years after completing their sentence. Marylanders with violent convictions seeking their voting rights were still required to apply for a gubernatorial pardon.14

In 2007, the varying rules for post-incarceration rights restoration were replaced with automatic restoration for all persons after sentence completion, resulting in an expansion of voting rights for more than 52,000 residents.14

Maryland lawmakers expanded voting rights to people completing their sentence on felony probation and parole in 2016 through House Bill 980, overriding Governor Lary Hogan’s veto.54 The reform expanded voting rights to an estimated 40,000 people.55

Minnesota: Voting Rights Restored to 46,351 People, 2023

In Minnesota, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Minnesota Disenfranchised Population | 55,192 | 1.3% |

| Black | 11,532 | 5.9% |

| Latinx | 3,281 | 2.6% |

* This table does not include 2023 reform

State lawmakers enacted legislation expanding voting rights to citizens completing their felony probation or parole sentence in 2023. About 84%, or 46,351, disenfranchised Minnesotans were completing their sentence outside of prison and thus affected by the reform.4

Nebraska: Rights Restored to 50,276 People, 2005-2022

Nebraska requires residents to wait two years after completing their prison, felony probation, or parole sentence to have their voting rights automatically restored.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Nebraska Disenfranchised Population | 17,960 | 1.3% |

| Black | 3,377 | 5.9% |

| Latinx | 4,701 | 5.5% |

In 2004, the Vote Nebraska Initiative issued a report with 16 recommendations designed to avoid electoral controversies like those that arose during the 2000 election in Florida. At the time, Nebraska imposed a lifetime voting ban for citizens with a felony conviction. While the report recommended automatic restoration of voting rights to people after completion of sentence, the 2005 policy change that followed imposed the two-year waiting period after sentence completion. Nonetheless, the 2005 change restored voting rights to an estimated 50,000 Nebraskans.14 Officials reported 44 Nebraskans had their voting rights restored from 2016 to 202029 and reported 232 individuals had their rights restored from 2020 through 2022.4

I was released from prison in 2018. Nevertheless, I will not be allowed to vote until I have been off supervision for two years. That means I will not have my voting rights restored until the year 2030...It gives me hope to see so many people across the country fighting to expand and protect the right to vote for people who have been impacted by the criminal legal system.

Nevada: Rights Restored to 77,000 People, 2016-2019

In Nevada, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Nevada Disenfranchised Population | 12,188 | 0.6% |

| Black | 3,785 | 1.9% |

| Latinx | 2,599 | 0.6% |

Prior to 2001, Nevada imposed a lifetime voting ban for all persons convicted of a felony offense unless their voting rights were restored by the Board of Pardons Commissioners or the sentencing court for those on felony probation. Individuals released from felony probation were required to wait six months to petition the board, and others had to wait five years after completing their sentence before applying for rights restoration. In 2001, the state eliminated this two-tiered waiting period and simplified the application process.4

During the 2003 legislative session, Nevada lawmakers adopted a measure automatically restoring the right to vote to any person convicted of a first-time nonviolent offense after completing their sentence.4

In 2017, Nevada policymakers adopted Assembly Bill 181, which restored voting rights to people who receive a “dishonorable discharge” from felony probation or parole. Previously residents who were dishonorably discharged from community supervision were banned from voting. The law also allowed people convicted of certain “category B” crimes (offenses that carry a minimum of 1 year to a maximum of 20 years in prison) to have their rights restored after a two-year waiting period.62 The number of people impacted is not known.

In 2019, Nevada lawmakers enacted legislation that automatically restored voting rights to people convicted of felonies but released from prison.63 Under the previous process, individuals released from prison had to petition the court to regain the right to vote through a cumbersome process. One analysis estimated 281 Nevadans had their rights restored over a 20-year period.64 The 2019 legislative change has led to the restoration of rights to 77,000 Nevadans.65

New Jersey: Rights Restored to 80,000 People, 2019

In New Jersey, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| New Jersey Disenfranchised Population | 13,999 | 0.2% |

| Black | 8,281 | 1.0% |

| Latinx | 2,341 | 0.3% |

The New Jersey Assembly enacted a comprehensive package of criminal legal reforms in 2010 that included a requirement that state criminal justice agencies provide individuals exiting prison with general information regarding state law and their eligibility to vote.14 People on felony probation and parole had their voting rights restored in 2019 by a law signed by Governor Phil Murphy. The change affected more than 80,000 people.67

New Mexico: Rights Restored to 80,000 People, 2001-2023

In New Mexico, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| New Mexico Disenfranchised Population | 17,572 | 1.2% |

| Black | 1,004 | 3.2% |

| Latinx | 9,949 | 1.5% |

* This table does not include 2023 reform

State lawmakers repealed the lifetime felony disenfranchisement ban in 2001 by restoring the right to vote to all citizens convicted of a felony upon completion of their sentence. The reform expanded voting rights to nearly 69,000 residents. To streamline the rights restoration process in 2005, policymakers implemented a notification process requiring the Department of Corrections to issue a certificate of completion of sentence to individuals who satisfactorily met obligations and to notify the Secretary of State when such persons become eligible to vote.14

The New Mexico Legislature adopted voting rights legislation that included a provision restoring voting rights to more than 11,000 residents on felony probation and parole in 2023.69

New York: Rights Restored to 35,000 People, 2018

In New York, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| New York Disenfranchised Population | 36,553 | 0.3% |

| Black | 18,115 | 0.9% |

| Latinx | 8,748 | 0.4% |

In 2010, the legislature required criminal justice agencies to notify people exiting felony probation or parole supervision of their right to vote. A formal notification was necessary because, according to reports, New York election officials regularly misapplied the law and some reportedly insisted persons provide unnecessary paperwork to prove their eligibility to vote.70

In 2021, the New York Legislature passed legislation that automatically restored voting rights to people on parole. The measure codified the voting rights expansion established via executive order in 2018 by Governor Andrew Cuomo. The executive order granted voting rights to 35,000 people under parole supervision by issuing conditional pardons to people on parole.71 The underlying law did not change, necessitating the legislature to enact subsequent statutory change.

North Carolina: No Estimate on Voting Rights Restoration Is Available

North Carolina prohibits all citizens convicted of a felony conviction in prison, on probation, or parole from voting.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| North Carolina Disenfranchised Population | 29,461 | 0.4% |

| Black | 15,148 | 0.9% |

| Latinx | 1,728 | 0.5% |

Voting rights are automatically restored upon completion of sentence and individuals can register to vote after filing a certificate demonstrating unconditional discharge with the county of conviction or residence. As in many other states, there has been concern that confusion about eligibility requirements and restoration procedures may prevent people from registering to vote in North Carolina. In 2007, the legislature passed a bill requiring the State Board of Elections, the Department of Corrections, and the Administrative Office of the Courts to establish and implement a program where individuals are informed of their eligibility to vote and given instructions on what steps to take to register.14

In 2019, a lawsuit was filed challenging the constitutionality of North Carolina’s felony disenfranchisement law, arguing that the law, which disproportionately impacts Black residents, restricts people from voting “based on impermissible race and class-based classifications.”73 Following a series of court rulings, people who were not serving felony sentences in jail or prison were authorized to vote through 2023. The legal battle concluded in April 2023 when the North Carolina State Supreme Court ruled to uphold the state’s disenfranchisement law.74

Rhode Island: Restoration of Rights to 17,000 People, 2006

In Rhode Island, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Rhode Island Disenfranchised Population | 1,606 | 0.2% |

| Black | 477 | 1.1% |

| Latinx | 447 | 0.5% |

Prior to 2006, Rhode Island was the only state in New England with felony disenfranchisement laws extending to persons on both felony probation and parole. Rhode Island voters approved a ballot referendum to amend the state constitution to expand voting rights to people on felony probation and parole in November 2006. The law restored the right to vote to more than 17,000 residents.14

Tennessee: Restoration of Rights to 5,449 People, 2016-2022

Tennessee bans people from voting who are in prison or on felony probation or parole, as well as individuals post-sentence who were convicted of a felony offense after 1981 and those convicted of select offenses prior to 1973. Individuals convicted of a felony in 1973-1981 never lost their voting rights.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Tennessee Disenfranchised Population | 471,592 | 9.3% |

| Black | 174,203 | 21.0% |

| Latinx | 10,531 | 8.2% |

Prior to 2006, eligibility and the restoration of voting rights varied based on offense type and conviction date. At that time Tennessee lawmakers enacted legislation simplifying the policy. Persons convicted of certain offenses after 1981 gained the right to apply for voting rights restoration with the Board of Probation and Parole following sentence completion. The 2006 law requires all outstanding legal financial obligations, including child support, to be paid before a person’s voting rights are restored.14 Officials reported 5,449 Tenneseans had their rights restored from 2016 through 2022.77

Now that I am out of jail, I continue to confront social, political, and economic discrimination because I have been convicted of a felony. After 50 years of mass incarceration and harsh sentencing policies, it’s time to remove this discrimination from our society and chart a better path forward.

Texas: Rights Restored to 317,000, 1997

In Texas, citizens can vote after sentence completion of their prison, felony probation, or parole term.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Texas Disenfranchised Population | 455,160 | 2.5% |

| Black | 126,388 | 5.2% |

| Latinx | 159,011 | 2.8% |

Texas has incrementally expanded voting rights to people with felony convictions since 1983. In that year the state repealed its lifetime voting ban for persons with felony convictions, replacing it with a five-year post-sentence waiting period.78, 79-94.)) In 1985 the waiting period was reduced to two years. In 1997, under Republican Governor George W. Bush, state lawmakers eliminated the waiting period and authorized automatic voting rights restoration after an individual’s sentence. The legislation expanded voting rights to an estimated 317,000 people.79

Utah: No Estimate Available

In Utah, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Utah Disenfranchised Population | 6,238 | 0.3% |

| Black | 450 | 2.2% |

| Latinx | 1,183 | 0.6% |

Utah allowed voting for citizens sentenced to prison with a felony conviction until 1998. A public referendum then amended Utah’s constitution to impose a voting ban for persons sentenced to a felony prison term. Those convicted in Utah had voting rights automatically restored after release from prison, but Utah residents convicted out of state were subjected to a lifetime voting ban. In 2006, this changed: the Utah General Assembly allowed automatic voting eligibility to all Utah residents after incarceration.14

Virginia: Voting Rights Restoration to 317,300 People, 2002-2023

Virginia disenfranchises all individuals with felony convictions for life unless the governor approves individual rights restoration.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Virginia Disenfranchised Population | 312,540 | 5.0% |

| Black | 147,164 | 12.2% |

| Latinx | 6,550 | 1.9% |

State lawmakers enacted several policy developments since 2000 to expand voting rights to Virginia residents and improve ballot access. In 2000, Virginia enacted legislation requiring the department of corrections to notify individuals under its jurisdiction about the state’s voting ban and the application process for rights restoration for those eligible.

Upon taking office in 2002, Governor Mark Warner streamlined the process of applying to the governor for voting rights restoration. He reduced the required paperwork from 13 pages to 1 for most people convicted of a nonviolent offense and decreased the waiting period to apply to three years following sentence completion. He also eliminated the requirement to submit three reference letters. During his administration, Gov. Warner restored voting rights to 3,500 Virginians, exceeding the combined total of all governors between 1982 and 2002. His successor, Governor Tim Kaine, continued this commitment to rights restoration, restoring voting rights to more than 4,300 persons while in office.81

In 2010, Governor Bob McDonnell streamlined the voter restoration process for individuals with felony convictions by decreasing the waiting period from three to two years. He also established a 60-day deadline for processing civil rights restoration applications after receiving corroborating information from courts and other agencies. These reforms reversed McDonnell’s initial restoration policy which required applicants to write a letter explaining why they wanted their voting rights restored.14 In 2013, Gov. McDonnell issued an executive order establishing an automatic rights restoration process for residents with nonviolent convictions who completed their sentence and paid all fines and restitution.83 The change both removed the waiting period and eliminated the application process. During his four years in office, Gov. McDonnell restored voting rights to nearly 7,000 Virginians.84

In 2016, Governor Terry McAuliffe leveraged his clemency authority to restore voting rights to approximately 200,000 Virginians who had completed their sentence. Opponents challenged the action in the state Supreme Court, which ruled rights restoration needed to be applied on an individual basis. Gov. McAuliffe subsequently restored voting rights to over 173,000 people.85

In 2021, Governor Ralph Northam issued an executive order to automatically restore voting rights to individuals upon completion of their sentence of incarceration.86 The change immediately affected more than 69,000 Virginians, and ultimately Gov. Northam restored voting rights to an estimated 126,000 Virginia residents during this term.87

Governor Glenn Youngking initially continued former Gov. Northam’s practice of automatically restoring the right to vote to all Virginians who are not currently incarcerated. However, he ended that practice sometime after May 2022. Nonetheless, an estimated 3,500 Virginians have had their rights restored during Gov. Youngkin’s administration.88

Washington: Voting Rights Restored to 20,000 People, 2021

In Washington, a person convicted of a felony loses their right to vote during imprisonment.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Washington Disenfranchised Population | 17,001 | 0.3% |

| Black | 2,976 | 1.6% |

| Latinx | 2,547 | 0.6% |

In 2009, Governor Christine Gregoire signed legislation that eliminated the requirement to pay all fines, fees, and restoration before regaining the right to vote. Previously, persons who completed their term of probation or parole but had not paid their legal debt were banned from voting. Further exacerbating the problem, legal system debts accrued 12% interest per year. Many individuals with felony convictions found it challenging to fully pay off their legal debts and subsequently were never able to receive rights restoration. Under the law change, individuals were still obligated to pay their criminal legal system debt, but not denied their voting rights.

Until 2021, people on felony probation or parole could not vote. Washington state lawmakers enacted legislation automatically restoring these rights to more than 20,000 on felony probation or parole.89

Wyoming: Voting Rights Restored to 4,282 People, 2003-2023

Wyoming restores voting rights only to those convicted of nonviolent felony offenses who have completed their sentence.

| Total | % Voting Age Population Disenfranchised | |

|---|---|---|

| Wyoming Disenfranchised Population | 10,306 | 2.4% |

| Black | 287 | 7.6% |

| Latinx | 1,040 | 3.3% |

In 2003, Wyoming authorized persons convicted of first-time, nonviolent felony offenses to apply to the Wyoming Board of Parole for a certificate to restore their voting rights following sentence completion after a five-year waiting period.90 Between 2003 and 2014, 82 people applied and had their voting rights restored.91

In 2015, Wyoming authorized automatic rights restoration for citizens convicted of first-time, nonviolent felony convictions who completed their sentence and subsequently eliminated the application process and the five-year waiting period for residents with qualifying conviction histories. Individuals convicted prior to 2016 and those with out-of-state and federal convictions were still required to apply for their voting rights following completion of sentence. An estimated 4,200 persons were eligible to apply for rights restoration at the time of the bill’s passage.92

Lawmakers passed House Bill 75 in 2017 to expand voting rights to individuals convicted of any nonviolent offense.93 Under this law, the Wyoming Department of Corrections automatically issues certificates of restoration of voting rights for any individuals who completed a qualifying sentence on or after January 1, 2010. Individuals with qualifying convictions outside of Wyoming or under federal law are required to submit a written request to the department, which issues voting rights restoration if it can confirm the individual’s eligibility. Although the total impact of the voting rights expansion is unknown, the Department of Corrections reports 3,708 Wyomians had their voting rights restored between 2014 and 2023.94

Executive Orders

While executive orders do not permanently reform state disenfranchisement policies, governors nationwide have issued orders to restore voting rights to hundreds of thousands of people. Listed below are examples of executive actions’ impact on restoring the right to vote. Subsequent governors revoked several of these orders.

| State | Governor | Year(s) | Rights Restored |

|---|---|---|---|

| Florida | Gov. Charlie Crist | 2007-2011 | 150,000 |

| Iowa | Gov. Tom Vislack | 2005 | 100,000 |

| Iowa | Gov. Kim Reynolds | 2020 | 20,000 |

| Kentucky | Gov. Steve Beshear | 2015 | 100,000 |

| Kentucky | Gov. Andy Beshear | 2019 | 140,000 |

| New York | Gov. Andrew Cuomo | 2018 | 35,000 |

| Virginia | Gov. Terry McAuliffe | 2016-2018 | 173,000 |

| Viginia | Gov. Ralph Northam | 2021 | 69,000 |

| Virginia | Gov. Glen Youngkin | 2023 | 3,500 |

Momentum for Reform

The right to vote in prison is recognized as an essential democratic practice both inside and outside of the United States. Indeed, the European Court of Human Rights affirmed in 2005 that bans on voting in prison violate the European Convention on Human Rights. Nearly half of European countries allow incarcerated people to vote, and Canada, Israel, and South Africa have ruled it unconstitutional to ban voting based on conviction status.95 There is no organized opposition to felony enfranchisement in any of these localities; nor is there such opposition in Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and the District of Columbia, where people convicted of felonies never lose their right to vote. In these jurisdictions, people in prisons can register (and remain registered) at their pre-incarceration address and can request absentee ballots by mail.96 Public opinion polls show that a majority – 56% of likely American voters – support voting rights for people completing their sentence inside and outside of prison.97

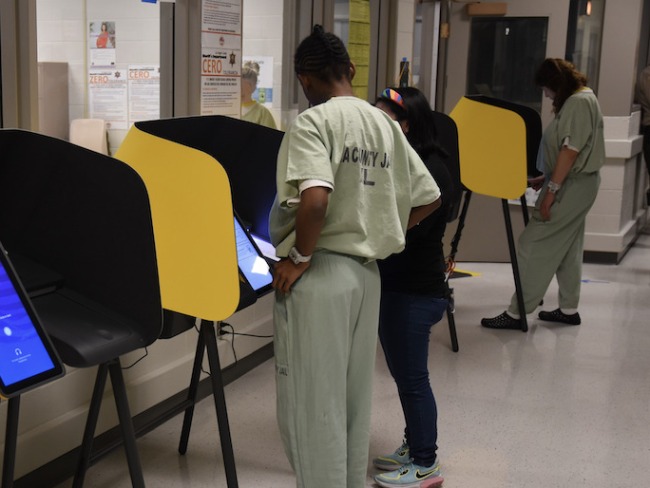

In recent years, various U.S. states and localities have worked to facilitate voting access by allowing in-person voting via polling stations at prisons or jails. In Puerto Rico, more than 6,100 people in prison voted in the 2016 Republican primary (the last known data available) where they comprised one-sixth of voters who cast their ballots.98 Officials in California, Colorado, Illinois, Texas, and Washington, DC have authorized polling stations at local jails while federal officials facilitated absentee voting for eligible voters in Bureau of Prison facilities.99

While the reforms that occurred in 1997-2023 are encouraging, much work remains to be done to end felony disenfranchisement and guarantee the right to vote for all Americans.

Appendix: progress advancing voting in jails

In local jails, the vast majority of citizens are eligible to vote because they are not currently serving a sentence for a felony conviction. Generally, people incarcerated in jail are unconvicted, sentenced to misdemeanor offenses, or sentenced and awaiting transfer to state prison. Of the more than 636,000 individuals incarcerated in jail as of 2021, over 451,000 were unconvicted. Of the 185,000 who were serving a sentence, nearly 20% were serving a misdemeanor sentence.100 In recent years, state and local officials along with civil rights, democracy advocates, and criminal legal reform groups have worked to guarantee ballot access for eligible voters in local jails.

- Colorado – Colorado law authorizes voting for persons held pretrial or sentenced to a misdemeanor. Colorado’s Secretary of State requires county clerks to submit a plan developed with county sheriffs on how eligible incarcerated people can register and vote from jail. In 2019, amendments were made to the Colorado Election Rules requiring county clerks to document ballot access for incarcerated residents.101

- Maryland – Incarcerated people in Maryland can vote in jail if they are pretrial or completing a misdemeanor sentence. In 2021, state lawmakers enacted measures to guarantee voting rights for persons incarcerated in local jails. House Bill 222, the Value My Vote Act, contains several provisions such as requiring the Maryland Department of Public Safety and Correctional Services to provide a voter registration application to eligible incarcerated persons.102 Lawmakers also passed Senate Bill 525, guaranteeing ballot access at the Baltimore City centralized booking facility by providing a secure, designated ballot drop box for people eligible to vote.103

- Massachusetts – In 2022, Republican Governor Charlie Baker signed Senate Bill 2554, the VOTES Act, into law. The comprehensive voting rights bill included provisions expanding ballot access in jails such as displaying posters explaining voting rights and procedures and written forms to distribute to everyone who may be eligible to vote. The law also directs jails to “ensure the receipt, private voting, where possible, and return of mail ballots.” It also requires sheriffs to track the number of people incarcerated in their jails who sought to vote, any complaints related to voting issues, and the outcome of those requests.104

- Nevada – In 2023, Nevada lawmakers passed Assembly Bill 286 to make an electronic absentee ballot system (currently used by individuals who are disabled or overseas) available to people who are pretrial in county and city jails. The bill also establishes a statewide process for same-day voter registration for those eligible to vote while incarcerated.105

| 1. | Nellis, A. (2023). Mass Incarceration Trends. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | All felony disenfranchisement estimates throughout the report come from Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022). Locked out 2022: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. Although data on ethnicity in correctional populations are unevenly reported and undercounted in some states, a conservative estimate is that at least 506,000 Latinx Americans or 1.7% of the voting eligible population are disenfranchised. |

| 3. | In 1973, the U.S. prison population began its unprecedented surge. By year end 2021, the prison population had declined 25% since reaching its peak in 2009. Nellis, A. (2023), see note 1. |

| 4. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 5. | This report is an update to The Sentencing Project’s report series, Expanding the Vote: 2008 thru 2018 which provided estimates of the number of people with felony convictions who have had their voting rights restored. |

| 6. | Porter, N. (2010). Expanding the Vote State Felony Disenfranchisement Reform, 1997-2010. The Sentencing Project; Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Pulido-Nava, A.. (2020). Locked out 2020: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project; Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 7. | Astor, M. (2018). Seven Ways Alabama Has Made It Harder to Vote. New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/23/us/politics/voting-rights-alabama.html |

| 8. | St. John, P. (2015). California could allow more felons to vote, in a major shift. Los Angeles Times. http://www. latimes.com/local/political/la-me-ff-elections-felons-vote-20150804-story.html |

| 9. | CBS SF Bay Area. (2016). Gov. Brown Signs Bill Giving Right To Vote To Thousands Of Felons. https://sanfrancisco.cbslocal.com/2016/09/28/gov-brown-signs-bill-giving-right-to-vote-to-felons-who-are-not-in-prison/ |

| 10. | Secretary of State Alex Padilla. (2020). Statement of Vote: General Election November 3, 2020. https://elections.cdn.sos.ca.gov/sov/2020-general/sov/complete-sov.pdf |

| 11. | McGreevy, P. (2020). Prop. 17, which will let parolees vote in California, is approved by voters. Los Angeles Times. https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-11-03/2020-california-election-prop-17-results |

| 12. | Pampuro, A. (2018). Colorado Bill Aims to Register 10,000 Parolees to Vote. Courthouse News Service. https://www.courthousenews.com/colorado-bill-aims-to-register-10000-parolees-to-vote/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId=46623c55-4c33-4499-b776-9d907a2244a6 |

| 13. | Paul, J. (2019). 11,467 Colorado parolees can now vote after the new law goes into effect. The Colorado Sun. https://coloradosun.com/2019/07/01/parole-felon-voting-colorado-laws/ |

| 14. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 15. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 16. | Senate Bill No. 1202. State of Connecticut June Special Session, Public Act No. 21-2. https://www.cga.ct.gov/2021/ACT/PA/PDF/2021PA-00002-R00SB-01202SS1-PA.PDF#page=125 |

| 17. | M, Vasilogambros. (2021). Connecticut Restores Voting Rights to People with Felony Convictions on Parole. Stateline. https://stateline.org/2021/06/25/connecticut-restores-voting-rights-to-people-with-felony-convictions-on-parole/ |

| 18. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 19. | House Bill 10. Delaware General Assembly. http://legis.delaware.gov/BillDetail?LegislationId=22921. |

| 20. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 21. | D.C. Law 23-277. Restore the Vote Amendment Act of 2020. Council of the District of Columbia. Retrieved here https://code.dccouncil.gov/us/dc/council/laws/23-277 |

| 22. | Austermuhle, M. (2020). For The First Time, D.C. Sends Voter Registration Forms To Residents Incarcerated For Felonies. The DCist https://dcist.com/story/20/09/03/dc-voting-rights-felony-enfranchisement-prisons-elections/ |

| 23. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 24. | Orlando Sentinel Editorial Board. (2018). Editorial: Reforming Florida’s unconstitutional process for restoring voting rights: Get on with it, Gov. Scott. https://www.orlandosentinel.com/opinion/os-ed-rick-scott-restore-felons-rights-20180329- story.html. |

| 25. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 26. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 27. | Hammerschlag, A. (2016). Estimated 1.7 million Floridians lost right to vote. Naples Daily News. https://www. naplesnews.com/story/news/politics/elections/2016/11/04/suppression-floridas-felon-vote-might-have-huge-impact-tuesdayselection/93136996/ |

| 28. | Committee Substitute Senate Bill 7066. Florida Legislature. http://laws.flrules.org/2019/162 |

| 29. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Pulido-Nava, A.. (2020), see note 6. |

| 30. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 31. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 32. | Niesse, Mark. 2020. “Georgia Election Officials Say Ex-Felons Can Vote While Paying Debts.” Atlanta Journal-Constitution, September 17, 2020. |

| 33. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 34. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2; Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Pulido-Nava, A.. (2020), see note 6. |

| 35. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 36. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 37. | Foley, R. (2012). Few Iowa felons win restoration of voting rights. The Gazette. https://www.thegazette. com/2012/06/25/few-iowa-felons-win-restoration-of-voting-rights. |

| 38. | Rodgers, G. (2016). Process to restore felon voting rights to be streamlined. Des Moines Register. https://www. desmoinesregister.com/story/news/crime-and-courts/2016/04/27/process-restore-felon-voting-rights-streamlined/83598488/. |

| 39. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., and Shannon, S. (2016). 6 Million Lost Voters: State-Level Estimates of Felony Disenfranchisement, 2016. The Sentencing Project. |

| 40. | Gruber-Miller, S. and Richardson, I. (2020). Gov. Kim Reynolds signs executive order restoring felon voting rights, removing Iowa’s last-in-the-nation status. Des Moines Register. https://www.desmoinesregister.com/story/news/politics/2020/08/05/iowa-governor-kim-reynolds-signs-felon-voting-rights-executive-order-before-november-election/5573994002/ |

| 41. | Philo, K. (2021). A GOP Governor and BLM Activists Agreed on Restoring Voting Rights to Felons. Will it Last? Politico Magazine. |

| 42. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 43. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 44. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 45. | Lopez, G. (2015). Kentucky’s old governor gave thousands the right to vote. The new governor took it back. Vox. https://www.vox.com/policy-and-politics/2015/11/25/9799148/kentucky-felons-voting-rights |

| 46. | Email with Damon Preston, Kentucky Department of Public Advocacy, on October 1, 2018. |

| 47. | Kenning, C. (2023). Kentucky restored voting rights to 178,000 with felonies. That’s not far enough, advocates say. Louisville Courier Journal. https://www.courier-journal.com/story/news/2021/01/28/kentucky-felon-voting-rights-must-go-farther-advocates-say/4258930001/ |

| 48. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 49. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 50. | Louisiana House Bill 265. (2018). https://legiscan.com/LA/bill/HB265/2018 |

| 51. | Voice of the Experienced. (2018). HB 265 is now a law! Find out who can now vote. https://www.vote-nola.org/ blog/hb-265-is-now-a-law-find-out-who-can-now-vote. |

| 52. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 53. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 54. | House Bill 980. General Assembly of Maryland. http://mgaleg.maryland.gov/webmga/frmMain. aspx?id=hb0980&stab=01&pid=billpage&tab=subject3&ys=2015rs |

| 55. | Ford, M. (2016). Restoring Voting Rights for Felons in Maryland. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/ politics/archive/2016/02/maryland-felon-voting/462000/ |

| 56. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 57. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 58. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Pulido-Nava, A.. (2020), see note 6. |

| 59. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 60. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 61. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 62. | Brennan Center for Justice. (2018). Voting Rights Restoration Efforts in Nevada. https://www.brennancenter.org/ analysis/voting-rights-restoration-efforts-nevada |

| 63. | Jackson, H. (2019). Nevada restores voting rights to formerly incarcerated. Nevada Current. https://www.nevadacurrent.com/blog/nevada-restores-voting-rights-to-formerly-incarcerated/ |

| 64. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., and Shannon, S. (2016), see note 39. |

| 65. | Jackson, H. (2019), see note 63. |

| 66. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 67. | Romo, V. (2019). New Jersey Governor Signs Bills Restoring Voting Rights To More Than 80,000 People. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2019/12/18/789538148/new-jersey-governor-signs-bills-restoring-voting-rights-to-more-than-80-000-peop |

| 68. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 69. | Gleason, M. (2023). Voting rights expansion bill heads to governor. Source NM. https://sourcenm.com/briefs/voting-rights-expansion-bill-heads-to-governor/ |

| 70. | Abramsky, S. (2018). At Long Last, Andrew Cuomo Restores the Vote for New York Parolees. The Nation. https:// www.thenation.com/article/at-long-last-andrew-cuomo-restores-the-vote-for-new-york-parolees/?eType=EmailBlastContent&eId= 745ee8e1-04c5-4d91-a8a9-4534e6078d72 |

| 71. | Abramsky, S. (2018), see note 70. |

| 72. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 73. | CSI v Moore. Brief amicus curiae of The Sentencing Project. 2022. https://www.sentencingproject.org/app/uploads/2022/10/CSI-v.-Moore-Amicus-Brief.pdf |

| 74. | Community Success Initiative v. Moore (N.C. Sup. Ct. No. 331PA21) https://appellate.nccourts.org/opinions/?c=1&pdf=42282 |

| 75. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 76. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 77. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Pulido-Nava, A.. (2020), see note 6.; Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022), see note 2. |

| 78. | Sennott, C., & Galliher, J. (2006). Lifetime Felony Disenfranchisement in Florida, Texas, and Iowa: Symbolic and Instrumental Law. Social Justice, 33(1 (103 |

| 79. | Uggen, C., Manza, J., Thompson, M., & Wakefield, S. (2003). Impact of Recent Legal Changes in Felon Voting Rights in Five States. The Sentencing Project. |

| 80. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 81. | McLeod, M. (2018). Expanding the Vote: Two Decades of Felony Disenfranchisement Reforms. The Sentencing Project. |

| 82. | Porter, N. (2010), see note 6. |

| 83. | Israel, J. (2013). Virginia Governor Automatically Restores Voting Rights To Nonviolent Felons. ThinkProgress. https://thinkprogress.org/virginia-governor-automatically-restores-voting-rights-to-nonviolent-felons-bfa4baa3ce5a/ |

| 84. | Richmond Times-Dispatch. (2013). McDonnell says state has restored rights of record 6,800 felons. https://www.richmond.com/news/latest-news/mcdonnell-says-state-has-restored-rights-of-record-felons/article_989ed33e-3759-11e3-b34e0019bb30f31a.html |

| 85. | Associated Press. (2018). Outgoing Va. Gov. McAuliffe says rights restoration his proudest achievement. https:// wtop.com/virginia/2018/01/gov-terry-mcauliffe-final-state-commonwealth/ |

| 86. | Office of the Governor. (2021). Governor Northam Restores Civil Rights to Over 69, 000 Virginians. https://www.governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/all-releases/2021/march/headline-893864-en.html |

| 87. | Schneider, G. (2022). Northam issues pardons in flurry of actions before leaving office. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2022/01/14/northam-pardons-virginia-governor/ |

| 88. | Schneider, G. (2023). Youngkin requires people convicted of felonies to apply for voting rights. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/dc-md-va/2023/03/22/youngkin-virginia-felon-rights-restoration/ |

| 89. | Associated Press. (2021). Gov. Inslee signs bill to restore voting rights to Washington parolees. NBC News. https://www.nbcnews.com/politics/elections/gov-inslee-signs-bill-restore-voting-rights-washington-parolees-n1263387 |

| 90. | Hancock, L. (2014). Wyoming committee studies restoring voting rights to felons. Star-Tribune. https://trib.com/ news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/wyoming-committee-studies-restoring-voting-rights-to-felons/article_3adc54b2-08ba58cb-854f-0ec689d40d14.html |

| 91. | Porter, N. (2016). The State of Sentencing 2015: Developments in Policy and Practice. The Sentencing Project, Washington DC. |

| 92. | Neary, B. (2014). Wyoming considers allowing some felons to vote. Associated Press. https://trib.com/news/state-and-regional/govt-and-politics/wyoming-considers-allowing-some-felons-to-vote/article_5e010552-171a-54e8-aef3-4298bc091201.html |

| 93. | Wyoming House Bill 75. (2017). https://legiscan.com/WY/text/HB0075/2017. |

| 94. | Wyoming Department of Corrections. (2023).See note 67 and Kiger, Stephanie. (Wyoming Department of Corrections) Email to Porter, Nicole D. (The Sentencing Project). 26 July 2023. |

| 95. | Chung, J. (2021). Voting Rights in the era of mass incarceration: A primer. The Sentencing Project. |

| 96. | White, A. & Nguyen, A. (2020). Locking up the vote? Evidence from Maine and Vermont on voting from prison. Massachusetts Institute of Technology. |

| 97. | The Sentencing Project. (2022). New National Poll shows Majority Favor Guaranteed Right to Vote for All. https://www.sentencingproject.org/fact-sheet/new-national-poll-shows-majority-favor-guaranteed-right-to-vote-for-all/ |

| 98. | Newkirk II, V. (2016). Polls for Prisons. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2016/03/inmates-voting-primary/473016/ |

| 99. | Awan, N. & Bertram, W. (2023). Jail-Based Polling Places Are Key To Expanding Ballot Access. Law 3600. https://www.law360.com/access-to-justice/articles/1690482/jail-based-polling-places-are-key-to-expanding-ballot-access; Department of Justice. (2022). BOP Voting Handout: Voting Rights for Incarcerated People. https://www.justice.gov/d9/fieldable-panel-panes/basic-panes/attachments/2022/03/23/bop_voting_handout.pdf |

| 100. | Zeng, Z. (2022). Jail Inmates in 2021 – Statistical Tables. The Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 101. | Porter, N. (2020). Voting in Jails. The Sentencing Project;. Clark, M. (2020). Most inmates in Colorado jails are eligible to vote, but access varies. Colorado Newsline. https://coloradonewsline.com/2020/10/30/most-inmates-in-colorado-jails-are-eligible-to-vote-but-access-varies/ |

| 102. | Legislation HB0222. (2021). Maryland General Assembly https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/HB0222?ys=2021RS&search=True |

| 103. | Legislation HB0222. (2021). Maryland General Assembly. https://mgaleg.maryland.gov/mgawebsite/Legislation/Details/sb0525?ys=2021RS&search=True |

| 104. | Nakua, K. (2022). New Massachusetts Law Requires Jails to Expand Ballot Access. Bolts Magazine. https://boltsmag.org/massachusetts-law-expands-voting-access-in-jails/ |

| 105. | Nevada Assembly Bill No. 286. (2023). https://s3.amazonaws.com/fn-document-service/file-by-sha384/47b41db655d0bda053c9280e8416f3cda504ed0ea43fabf454b299251a0f1cc7c352938ec9a56936276085028dba2505 |