Voting From Prison: Lessons From Maine and Vermont

Incarcerated citizens in Maine and Vermont still face significant barriers to casting a ballot. With an estimated one million eligible voters currently completing a felony-level sentence in prisons or jails across the U.S., the findings underscore the urgent need to remove systemic barriers to voting in correctional facilities.

Related to: Voting Rights

Executive Summary

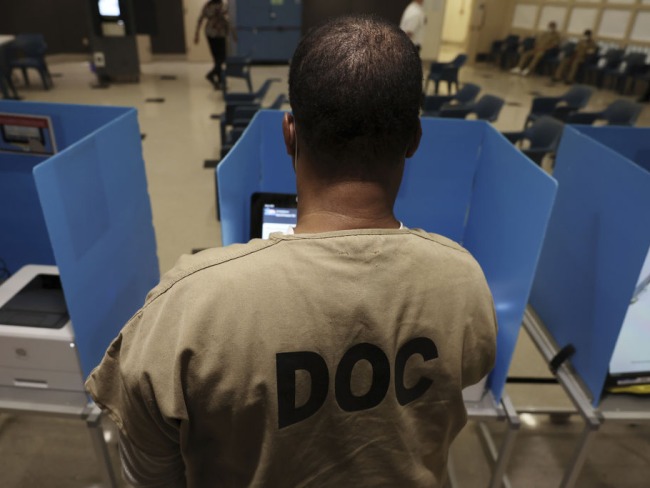

Only two U.S. states – Maine and Vermont – do not disrupt the voting rights of their citizens who are completing a felony-level prison sentence.1 Incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters retain their right to cast absentee ballots in elections. Because of the states’ unique place in the voting rights landscape, The Sentencing Project examined how their Departments of Corrections facilitate voting. We sought to determine experiences and lessons to share nationally as momentum builds in states, such as Illinois, Maryland, and Oregon, to expand voting rights to people completing a felony-level sentence in prison or jail.2

Voting is one prosocial way to maintain a connection to the community, which is particularly important during incarceration, and it helps to build a positive identity as a community member.3 The right to vote is also an internationally recognized human right.4 While voting is a cornerstone of American democracy, an estimated 1 million citizens cannot vote because they are completing a felony-level sentence in prison.5 Given racial disparities in incarceration, people of color are disproportionately blocked from the ballot box due to voting bans for people with a felony-level conviction.6

This first-of-its-kind research is a culmination of a multi-year inquiry in Maine and Vermont about how voting rights are implemented in prisons. The Sentencing Project sought to answer two interrelated questions:

- What are incarcerated residents’ views about voting and the voting process?

- What are the facilitators and barriers to implementing voting rights within the Department of Corrections, according to Department of Corrections staff and other stakeholders?7

Past research has found low voter turnout among people incarcerated in these states, despite incarcerated residents retaining their voting rights while completing a felony-level sentence.8 This suggests that, in practice, the absentee ballot voting process may be more complex in correctional settings.9

Our findings are based on 21 interviews with staff from the Maine and Vermont Departments of Corrections and other stakeholders who collaborated with these agencies in voting rights work, as well as our survey of incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters in which 132 incarcerated people participated. This investigation revealed:

- Nearly three quarters (73%) of incarcerated survey respondents said that voting during incarceration is important to them.

- Almost half (49%) of incarcerated respondents said that they did not know how to vote at their facility.

- Facilitators that supported voting within the Departments of Corrections included:

- Involvement of the Secretary of State’s Office, non-profit groups, and individual volunteers.

- Cooperation from the Departments of Corrections’ administration and staff.

- Coordination of in-person voter registration drives to assist incarcerated residents with the voter registration process.

- Barriers that hindered voting within the Departments of Corrections included:

- Incarcerated residents’ lack of knowledge about their voting rights and how to navigate the multiple-step process to vote absentee.

- Limited information about candidates to inform voters and a lack of guidance on voting dates and deadlines.

- A lack of staff training on incarcerated residents’ voting rights and how to assist incarcerated residents with voting.

- Additional logistical challenges included:

- Limited access to the paperwork needed to vote (e.g., registration forms, ballot requests).

- Delays caused by prison mail and mail external to the facility.

- A lack of person-power or capacity by corrections staff and other stakeholders to conduct voting rights work across all facilities.

Based on these findings, The Sentencing Project recommends providing more equitable access to voting and democracy during imprisonment by:

- Establishing on-site polling locations in all correctional facilities that have eligible voters.

- Expanding education for incarcerated residents about their voting rights and how to vote using an absentee ballot method.

- Training corrections staff on incarcerated residents’ voting rights and on the process of assisting residents who are voting from prison.

- Increasing access to candidates and candidate information, including hosting candidate forums within the prison.

- Permitting and providing access to official government websites as additional avenues to register to vote, request ballots, track ballots, and learn about state and local ballot initiatives.

Such a vision for voting in prisons is attainable. A movement is already underway to increase access to the ballot in jails.10 Due to the fluidity of jail populations – where an average stay is 32 days – coordinating voting efforts in jails can be even more complex.11 Yet, even with such hurdles, turnout in jails with on-site polling locations has surpassed citywide turnout rates in places like Cook County, Illinois and Washington, DC.12 The successful implementation of jail-based voting demonstrates that prison-based voting is possible. Every eligible American citizen should be able to cast a ballot in elections regardless of conviction or incarceration status. In the words of one incarcerated resident in Maine, “I believe strongly [that] voting is a fundamental right for every American citizen. Being incarcerated does not mean you forfeit that right so I voted in here and will most definitely vote out of here.”

Introduction

Based on 2024 estimates, over 1 million voting age citizens cannot vote because they are in prison completing a felony-level sentence.13 This banishment from participation in democracy falls heavily on people of color as a result of the disproportionate incarceration of Black and Latino citizens in our nation’s prisons.14 Voting bans run counter to research that supports the benefits of voting for justice-impacted people, most of whom will return to their communities.15 It also silences American citizens with diverse political views. A survey of over 54,000 incarcerated people in 45 states found that a substantial minority of incarcerated people identified as an independent (35%) followed by Republican (22%) or Democrat (18%).16 Blocking access to voting due to incarceration status weakens our democracy.

Today, very few jurisdictions in the United States can claim to have an inclusive democracy where every voting age citizen, regardless of conviction or incarceration status, has the right to vote. Yet, momentum continues to build in the movement to restore voting rights to people in prison.17 In 2020, Washington, DC expanded the right to vote to DC residents who are completing a sentence for a felony-level conviction.18 DC’s Restore the Vote Amendment Act of 2020 allowed it to join Maine, Vermont, and Puerto Rico in ensuring that every eligible voter – regardless of incarceration status or conviction offense – can vote.19 Advocacy in other states, such as Illinois, Maryland, and Oregon, also seeks this criminal legal reform – to expand the vote to people in prisons.20

Given this ongoing work in jurisdictions to restore voting rights to people in prison, now is the time to better understand what helps or hinders the voting process during imprisonment. Maine and Vermont are the only two states that have not stripped voting age citizens of their right to vote when they are completing a felony-level sentence. Their work can act as one of the important guides as the movement to unlock the vote for justice-impacted people continues. To that end, The Sentencing Project undertook a multi-year research endeavor to understand how voting unfolds in Maine and Vermont prisons. Our investigation encompassed two broad areas of inquiry:

- What are incarcerated residents’ views about voting and the voting process?

- What are the facilitators and barriers to implementing voting rights within the Department of Corrections, according to Department of Corrections staff and other stakeholders?

To answer these questions, we took a multi-faceted approach. In addition to our survey of 132 incarcerated residents in Maine and Vermont, we interviewed 10 corrections staff and 11 other stakeholders.21 Stakeholders provided insights on how they collaborated with their Department of Corrections on voting rights implementation. From these discussions, we identified several universal facilitators and barriers to voting rights work that existed in both Maine and Vermont. This report also highlights facilitators and barriers unique to each state.

Our hope is that the findings herein will help inform best practices for ensuring voting access for incarcerated people nationwide.

…all elections ought to be free and without corruption, and that all voters, having a sufficient, evident, common interest with, and attachment to the community, have a right to elect officers, and be elected to office, agreeably to the regulations made in this constitution.”

VT. CONST. Ch. I, art. VIII.

Established July 9, 1793, amended through December 14, 2010

Voting Rights, Constitutions, and Felony-Level Convictions in Maine and Vermont

Historical Context

During early statehood, Maine and Vermont individually debated instituting voter disenfranchisement for felony-level convictions. In Maine, this proposal was met with strong resistance during the state’s constitutional convention.22 Critics of these laws said they left no room for rehabilitation and the capacity for change.23 According to historical accounts, only one person – the person who brought forth the proposal – supported disenfranchisement on the rationale it would deter criminal behavior. In Vermont, a 1797 law allowed the state supreme court to strip voting rights for convictions “of bribery, corruption, or any ‘evil practice’ that rendered him ‘notoriously scandalous.’”24 By 1800, the Third Council of Censors recommended disenfranchisement be tailored narrowly to election-related offenses.25 The Vermont legislature adopted this recommendation in 1832. Today Maine’s and Vermont’s constitutions permit disenfranchisement for very narrow election-related offenses (e.g., bribery), but they have been steadfast in not stripping citizens of their voting rights as a form of punishment.26

Contemporary Practice

In both states, incarcerated residents who established residency in the state prior to their incarceration may vote by absentee ballot. Those who have not yet registered to vote are required to complete a registration form using their last known community address (not the prison address).27 Once the voter registration form, and any other required forms (e.g., proof of identification, proof of residency), is mailed, reviewed, and accepted by the Town Clerk, incarcerated voters can request an absentee ballot by mail. Once the absentee ballot is mailed to the facility, incarcerated voters can make their selections and return their ballot, again using the mail. When taken at face value, this seems like a straightforward and simple process. However, researchers have found low voter turnout rates in Maine and Vermont correctional facilities – suggesting that, in practice, the process may not be so simple after all.28

Part 1: Incarcerated Mainers’ and Vermonters’ Views on the Importance of Voting and the Gaps in Their Voting Knowledge

Most of the incarcerated survey respondents thought voting is important. Yet a substantial number reported that they had not voted in an election during their incarceration. The survey responses tell us that there is a lack of understanding about how to vote from prison. Incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters were learning that they can still vote from each other instead of learning from their Department of Corrections. They also identified numerous supports that would be helpful with voting.

Being able to vote both as a felon and incarcerated is extremely important…voting returns a sense of humanity to us in a place where that rarely happens. Personally, it also returns the feeling that I’m still part of society, this nation, and the community.”

– Incarcerated resident, Maine29

Most of the incarcerated survey respondents thought voting is important. Yet a substantial number reported that they had not voted in an election during their incarceration. The survey responses tell us that there is a lack of understanding about how to vote from prison. Incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters were learning that they can still vote from each other instead of learning from their Department of Corrections. They also identified numerous supports that would be helpful with voting.

Having the right to vote is important during incarceration. Over 73% of survey respondents answered affirmatively that voting while they were incarcerated is important to them.30 Here are some of the reasons they gave about the importance of being able to vote during incarceration:

- Voting is an inalienable right and part of American citizenship.

- Voting is a right of citizenship and citizenship is not lost due to a felony-level conviction nor incarceration.

- Voting is a way for their voice to be heard on laws and policies that affect them and their families.

Incarcerated residents also touched on voting in relation to democracy and having representation that reflects their views and values. Others pointed to voting’s general importance and that it was the right thing to do. In the words of one incarcerated resident from Vermont who strongly disagreed that individuals should lose their right to vote if convicted of a felony, “Just because you commit a crime does not mean that you are no longer a citizen. You are still a member of society and should have a say in how you are governed.”

Of the 107 survey respondents who were incarcerated during an election, roughly 39% reported that they had voted during their imprisonment.

Many incarcerated residents do not know how to vote at their facility. While voting during incarceration was viewed by many as important, almost half (49%) of the respondents said they did not understand how to vote at their facility.31 Among residents who had been incarcerated during an election, those who voted were significantly more likely to understand the voting process compared to residents who did not vote.32 This relationship makes sense and should not come as a surprise — understanding the process of how to vote at the facility and whether one does actually vote.

Incarcerated residents mostly learn from other incarcerated people that they can still vote. When we asked, “When you entered the facility, when did you learn you could vote in elections?,” nearly a quarter (22%) of respondents answered “never.”33 For another 19%, it took more than six months until they learned about their right to vote. Only 11% of respondents recalled learning they could vote on the day they arrived at the facility.34

When we asked how they were informed about their voting rights, half of the respondents reported that they found out they could vote from other incarcerated individuals.

| Options: | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Other incarcerated resident | 50% |

| Department of Corrections staff member | 11% |

| Case manager | 10% |

| Other | 36% |

Note: n=127 respondents. Respondents could choose more than one response option; therefore, percentages do not add up to 100%.

Respondents wrote about “other” ways they learned they could still vote, the next highest response category, including previous knowledge prior to incarceration, when they took our survey, Department of Corrections announcements, volunteer or civic groups, and various other outlets (e.g., television). Learning about one’s voting rights from Department of Corrections personnel – such as staff members or case managers – was not the norm.

What would help incarcerated residents with voting? To uncover what incarcerated residents would find most helpful when it comes to voting, we asked them to rate possible resources from “not at all helpful” to “very helpful.”

| Options: | Very helpful, percentage |

|---|---|

| Information about candidates | 77% |

| Election cycle calendar with important dates | 72% |

| Class or program on voting, elections, and government | 54% |

| A peer or mentor to help with voting | 47% |

| A staff member to help with voting | 41% |

Note: Not all survey takers ranked all items. Sample sizes: Candidate information, n=126 respondents; calendar/dates and class or program, n=125 respondents; and peer or staff mentor, n=124 respondents.

Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that information about candidates would be very helpful, and elections calendars listing important dates would also be very helpful. Our report will provide context for these findings.

Part 2: Universal Facilitators that Support Voting – Partnerships, Cooperation, and In-Person Registration Drives

Universal facilitators are factors we identified in Maine and Vermont that supported incarcerated residents with voting or, in general, the facilitation of voting rights work within the prisons. Universal facilitators included the involvement of stakeholders in facilitating voting rights work, the Department of Corrections level of support and cooperation, and the availability of in-person voter registration drives.

Key external stakeholders play a pivotal role in supporting voting rights work. In both Maine and Vermont, it was clear that external stakeholders played a pivotal role in voting rights work, particularly with regard to in-person registration. While collaborations varied by state, external stakeholders included a wide variety of people ranging from staff from the Secretary of State’s Office, staff from Disability Rights Vermont,35 volunteers from the League of Women Voters, as well as representatives or other organized civic and nonprofit groups and individual volunteers. In Vermont, a corrections staff member said that the organizations and volunteers that assist with voting are “the glue that keeps the whole voting thing together.” Another Vermont staff member expressed “we really appreciate that they do [help us], and we really value the efforts they give us because it is something that is a big help to the department in regards to the voting.”

The Secretary of State’s Office was an important asset discussed by staff in Maine. The Maine Department of Corrections Administration permitted staff from the Secretary of State to bring in computer equipment so that they could hardwire into their central voter registration system. This allowed voter registration to be accomplished in real time. Their presence within the facilities was often talked about in terms of efficiency, and included things such as:

- identifying new registrants, or the need for updated registration or an absentee ballot request form;

- addressing real-time discrepancies on voter registration forms or ballot requests;

- providing required notarization of the Proof of Residency/ID form; and

- acting as a liaison between the corrections staff and Town Clerk’s office to make corrections on voting forms, when necessary.

During the 2022 election cycle, the paperwork was then physically transported and managed by the Secretary of State’s Office instead of making incarcerated residents mail it to their corresponding Town Clerk. It is unknown if the Secretary of State’s Office continued this level of support during the 2024 presidential election cycle.

Departments of Corrections support and cooperation make voting rights work a feasible reality. The Department of Corrections is the gatekeeper to “if and how” the voting work unfolds, including who has access to do this work. One Maine stakeholder commented “I think the fact that the Department of Corrections is a willing participant and willing partner…to do voter registration education, I think that makes everything a lot easier.” This included being a critical liaison for external partners to come in and conduct voter registration drives, which included background checks, equipment approvals, logistics and security. In Vermont, stakeholders made numerous positive comments about the facility staff, such as “One thing they do well is they welcome volunteers.” Others relayed how staff were helpful with logistics, including distributing sign-up sheets, arranging locations within the facility to conduct the voting rights work, and bringing incarcerated residents or units to the designated area(s) in line with security protocols. This left stakeholders in Vermont with the feeling that the “…department’s very helpful and committed to making sure that [voter registration] can happen.”

In-person voter registration drives are at the heart of implementing voting rights. Staff and stakeholders note that they observe the highest level of interest from incarcerated people about voting during the in-person registration events. It is an opportunity for incarcerated residents to easily seek help with filling out their voter forms and any other required documents. It also presents an opportunity to catch errors on forms in real time. The high level of interest corresponds to a finding from our survey – incarcerated voters want access to in-person voter registration events.

| Options: | Very helpful, percentage |

|---|---|

| In-person voter registration event | 64% |

| Staff give you voter registration information | 47% |

| Voter registration forms are put in the common area | 40% |

Note: n=126 respondents. Respondents could choose more than one response option; therefore, percentages do not add up to 100%.

Each state takes its own approach to voter registration drives. In Vermont, in line with their guidance document, staff are tasked with holding one event at least 90 days in advance of an election. They often partner with stakeholders to accomplish this work. In Maine, the NAACP prison branch does the work to organize the voter drive with approval from the Department of Corrections. During our research, some corrections staff also reached out to the Secretary of State’s Office to inquire about registration drive support.

Unique facilitator in Maine: The NAACP Prison Branch

The backbone of the voting rights work in Maine is facilitated by the on-site NAACP prison branch, an internal stakeholder. Incarcerated residents founded the NAACP prison branch in the early 2000s and continue to lead the branch today. They work to inform other incarcerated residents about their right to vote. The prison branch organizes and runs in-person voter registration drives, provides voter education opportunities, and brings in guests and state legislators. They work with incarcerated residents who may not be able to read or write, and recruit key Department of Corrections staff members to assist them with their efforts. There is recognition both inside and outside the prison in regard to the importance of the NAACP prison branch’s voting rights work:

“…I asked the administration [about voter registration]. They [the administration] hadn’t done anything yet or heard anything regarding it. And they referenced me to the NAACP chapter as being the driving force behind it.”

– Staff member, Department of Corrections

“…the Maine Chapter of the NAACP…they have historically been the ones leading the charge and ensuring that voters who are incarcerated get registered and then get absentee ballot requests.”

– Stakeholder

Unique facilitator in Vermont: The voting rights policy and staff guidance document

In 1980, Vermont’s Voting Policy 969 went into effect stating that all correctional facilities are to “protect the voting rights of inmates in correctional institutions, and to mandate development of facility procedures for inmate voting.”36 The most current policy’s philosophy is “to ensure that inmates are made aware of their right to vote while incarcerated, and to encourage inmates to vote.”37 To clarify staff roles and responsibilities, Vermont has a corresponding staff guidance document that specifies voter qualifications, how to inform incarcerated residents of their right to vote, including holding “voter informational and registration clinics” biannually, and details staff responsibilities for this work.38 Staff doing the voting rights work viewed this guidance document as a critical tool.

Part 3: Universal Barriers that Impede Voting – Lack of Information and Lack of Staff Training

Universal barriers are factors we identified in Maine and Vermont that make it more difficult to vote during incarceration. Universal barriers included incarcerated residents’ lack of knowledge about voting and voting related issues. Another barrier was the lack of staff training to facilitate voting.

Incarcerated residents lack sufficient voter information. Conversations with corrections staff, stakeholders, and the insights from the resident survey make it clear that incarcerated residents had many gaps in their knowledge surrounding voting. These included:

- Being unaware that they can still vote;

- Lacking information about candidates running for office to be well-informed voters; and

- Scant information regarding important voting dates and deadlines.

Incarcerated residents can still vote?

I was told with being a felon, I have lost the right to vote.”

– Incarcerated resident, Maine39

I was unaware that a felon can vote!!”

– Incarcerated resident, Vermont40

There was consensus from our interviewees, both staff and stakeholders, that many incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters held the misperception that they could not vote. In our surveys, some residents used their written responses to tell us that they did not realize they had retained their right to vote during incarceration. Through our discussions with Maine and Vermont corrections staff, it became apparent there were no clear answers about who was supposed to tell incarcerated residents about their voting rights – a clear indicator for why incarcerated residents may not understand that they can still vote. There was also a lack of consistency about how this information was relayed across all of the facilities. In Vermont, a staff member explained “So really the [facility] handbook and if they happen to stumble upon it in the law library or [during other] education. Those are really the only places that I can think of that they’d initially find out [about their right to vote].” In Maine, similar patterns emerged as staff hypothesized about the ways they thought incarcerated residents learned about their right to vote: at intake or orientation, from TV/screen monitors in units, or when it is time to sign people up to register to vote. To illustrate the inconsistency in how such information is (or is not) shared, a Maine staff member noted that “one of the facilities mentions it in their handout, their intake orientation. We don’t.”

How do incarcerated residents decide who to vote for?

Just because you go to prison doesn’t mean you have to go to a black hole of information. You should have the right to learn what’s happening outside and the social issues or the political issues that are going on outside of the place where you’re incarcerated.”

– Stakeholder, Maine

Our survey asked incarcerated residents if they were able to access information about candidates running for office. Over half of the respondents said they could not.

| Options: | Percentage |

|---|---|

| No | 55% |

| Yes, for all the candidates | 26% |

| Yes, but only for some of the candidates | 19% |

In response to multiple open-ended questions, incarcerated residents reiterated concerns about the lack of voter information. Their answers illustrate the essential nature of this information and how lacking candidate information may influence their decision to vote or not:

Have you voted since being incarcerated?

- “No, don’t have enough information on candidates” – Vermont

- “No…it is hard to listen and read about what each candidate is saying and doing other than television” – Vermont

What would make it easier to vote while you’re incarcerated?

- “Better access to political information…” – Maine

- “More information about candidate opinions” – Maine

- “Have the people running come in” – Maine

- “Learn about process and candidates” – Vermont

“Information about candidates” – Vermont

What makes it harder to vote while you’re incarcerated?

- “Lack of info about candidates” – Maine

- “Not having candidates come in and talk about their agenda” – Maine

- “No candidates to come speak or care about winning our vote” – Vermont

- “They don’t provide enough info on how to vote and on the candidates” – Vermont

When we asked corrections staff in Maine and Vermont how incarcerated residents were able to access information they needed to be informed voters, there was consensus that “it’s a very limited information stream,” as one Maine staff member put it. The majority of staff all commented on access to television in a common area, but it is more likely than not national rather than state or local news. Therefore, residents would still need to have other sources of information for state and local issues and candidates. Staff also mentioned newspaper or magazine subscriptions, but much of these must be purchased by residents, may not be region specific, and are limited in quantity (although some staff mentioned incarcerated residents may pass on hardcopy publications, like newspapers and magazines, to other incarcerated residents). In Maine, staff noted that incarcerated college students may have access to the internet. External stakeholders in both states stressed the importance of providing incarcerated residents access to media so that they could learn about who is running; ensuring that information, such as newspapers (subscriptions or otherwise) and voter information packets, are available on residents’ tablets; and hosting live-stream debates or bringing candidates into the facilities to discuss their positions and platforms.

I think it would be extremely helpful for all residents to receive all the information about candidates and maybe they would like to vote. Every vote counts, every person matters.”

– Incarcerated resident, Maine

What are the dates and deadlines? How do incarcerated residents know when to mail their voter registration forms, absentee ballot requests, and ballots?

I never know when it’s time to vote. I’m in closed custody most of the time, and [they] never tell me how or when to vote.”41

– Incarcerated resident in high-security closed custodial confinement,

Vermont

Only 14% of survey respondents said they were reminded by facility staff about important voting dates and deadlines.42 In Maine, when we asked staff members if they provided due date and deadline reminders for voting activities, such as voter registration or requesting ballots by mail, one staff member said that this was done on a “case-by-case individualized basis” or only if staff members took it upon themselves to write something to post. Another staff member reminded incarcerated residents about mail speed, which was a somewhat indirect way of highlighting deadlines. In Vermont, most staff said they put flyers and posters in the units or in the facility which included relevant dates and deadlines. Two staff members noted that they also leveraged tablets to send information and reminders. Nevertheless, a vast majority of incarcerated residents said they were not getting reminders, which may be why 90% of surveyed incarcerated residents reported that an election cycle calendar with important dates would be “very helpful” or “somewhat helpful” to them.43

A Consensus on the Need for More Voter Education for Incarcerated Residents

“I think if we educated the folks, the incarcerated individuals, a little more thoroughly on voting and things, that would also help to increase [the number] of people actually participating in voting.”

– Staff member, Vermont Department of Corrections

“It’s important that people know what they’re voting for, know who they’re voting for, know what some of the terminology and initiatives and proposed policies mean.”

– Staff member, Maine Department of Corrections

Corrections staff and stakeholders who were interviewed recognize that incarcerated Mainers and Vermonters need more voter education, which would include the “nuts and bolts” of how to vote, including the separate processes of registering and then requesting a ballot. Voter education was also more broadly defined (e.g., why voting matters, explaining the difference between political parties, learning about state and local politics). Interviewees’ specific suggestions for voter education included:

-

- Creating a culture of awareness so incarcerated residents know they maintain their right to vote;

- Educating incarcerated residents on how to vote – starting with the initial two-step process (registration + ballot request);

- Offering all incarcerated residents a variety of voter education and civic education opportunities, such as workshops on voter education and the basics of government, as well as institution-wide civics classes (perhaps for credit or a certificate);

- Uploading voting resources to tablets for free;

- Distributing election-specific information, particularly at the state and local levels on candidates and voter referendums; and,

- Providing access to qualified people or resources that can explain proposed voter initiatives and referendums.

The survey results from our incarcerated residents mirrored these findings – 80% of surveyed residents responded that a class or program on voting, elections, and government would be “very helpful” or “somewhat helpful” when it comes to voting.44

Unique barrier in Maine: Lack of voting rights infrastructure

Maine has neither an official voting rights policy nor a formal write-up for staff guidance on how to guide incarcerated residents to exercise their voting rights. Our interviewees said that at least some staff – especially new staff – are unaware that voting rights are retained during incarceration. Other staff members encountered a lack of guidance on how to execute their job duties related to voting rights. Moreover, staff members wondered, what if the work of the NAACP prison branch or Secretary of State’s Office ceased? One staff member relayed: “…we have [incarcerated] individuals that are mainstays here that either move to a lower security facility or get released, and all of a sudden, all that knowledge and helpfulness goes with them, unless there’s somebody else to follow in their footsteps” (our emphasis added). Creating a written policy would define the rights of incarcerated residents clearly, help to develop effective voting rights practices, and also establish a way for the processes and protocols to be retained as institutional knowledge within the Maine Department of Corrections.

Unique barrier in Vermont: Underuse of online voter registration

The internal guidance document, outlining Vermont staff’s roles and responsibilities, states that the “Volunteer Services Coordinator or designee may also access the online voter registration webpage and work with the inmate to fill out the online registration.”45 Because incarcerated residents cannot go online, a staff member must fill out the form using information provided by the resident. The guidance document clarifies that “online registration does not require individuals to provide a hard copy of the required documentation, and therefore may be an easier option for many inmates.”46 However, to our knowledge, no staff member has used this option. Staff expressed concerns about staffing capacity to do the work as well as staff’s level of comfort in using the online portal. External stakeholders noted it would save time and avoid problems caused by mail delays if online registration were used more readily.

Staff lack sufficient education on incarcerated residents’ voting rights and how to assist with voting. In each facility in Maine, the Volunteer Services Coordinator or a designee is assigned to implement the voting rights policy. In Vermont, we did not find a consistent staff voting rights designee across facilities. To illustrate, some staff were recruited for this role by incarcerated residents and others found out during the course of performing their duties that their job also included voting rights work. Regardless of how staff are assigned or assume these roles, the staff we spoke with in both states were doing their best to learn on the job about how to approach voting rights work and assist incarcerated residents with voting. They agreed that formalized training would be beneficial, including important foundational information for all staff (e.g., incarcerated residents maintain the right to vote). They noted the need for flexibility within written policies, because voting rights work is one of their many job duties and this work may vary by the type of facility and population they serve (e.g., shorter-term versus longer-term incarcerated residents). Training and formal guidance on voting rights work would also address staffing changes or turnover.

I’m having a tough time understanding everything that I’m supposed to be doing [with voter registration]…It was handled by somebody else, so it’s fallen to me and so I am a little ignorant about all of the steps that I need to take to get this done.”

– Staff member, Maine Department of Corrections

So, would I like to attend a training regarding voting? I would. Is there any offered? I don’t believe there is.”

– Staff member, Vermont Department of Corrections

Part 4: Additional Logistical Challenges in Voting Rights Implementation – Accessibility, Mail, and Capacity

Everything in prison is 100 times harder than it is on the streets.”

– Staff member, Maine Department of Corrections

Accessibility of voter registration forms and the logistics of absentee ballots in prison need improvement. In both Maine and Vermont, incarcerated residents expressed a desire for more access – “better access to the paperwork needed to vote” (Vermont) and also brought up the “limited avenues to register to vote” (Maine). As noted, while 64% of respondents desired in-person registration events, a critical access point for incarcerated people, a substantial number of respondents indicated they would like other ways to register as well. This included having staff distribute voter registration forms (47%) and having access to forms in a common area (40%).

Incarcerated residents also noted many obstacles they faced when trying to obtain an absentee ballot. These challenges included the logistical steps to request a ballot (e.g., writing to the Town Clerk, finding the address for the correct Town Clerk), the time it takes for ballots to be mailed to the facility, or what to do after requesting a ballot but not receiving it, among other dilemmas. Here are some illustrative examples:

What would make it easier to vote while you’re incarcerated?

- “The time it takes to get the ballot to and from me – time constraints” – Maine

- “If I got my absentee ballot without having to write for them” – Maine

- “If the ballots showed up. Mine did not, twice” – Maine

- “To have the ballots of/for the registered voters sent to the prison/facility to lessen the burden of trying to get them from the Town Hall or City Hall” – Maine

- “How to get absentee ballots, a list of the town hall addresses, etc.” – Maine

- “Getting a ballot” – Vermont

- “Ballots being readily available” – Vermont

- “Passing out the ballots…during the time of year or make available on our canteen list to order for ourselves” – Vermont

Staff recognize this is a laborious process for the residents who want to vote. A Vermont staff member offered this thought: “One barrier that our incarcerated individuals have is that it is a significant amount of work, the absentee ballot process. You got to find your Town Clerk, you got to send in the ballot [request], you got to wait for it to come back, you got to fill it [the ballot] out, you got to send it back.”

The unpredictable nature of prison mail is an impediment to absentee ballot voting. The prison mail system is directly related to access issues. Interviewees all grasped the importance of the mail system, and because of how it functions, they understand the necessity of more lead-time for receiving and sending important voting documents. While Vermont staff were less concerned with the processing speed of internal mail, in general, staff members and stakeholders did note that the mail process external to the facility could cause delays. This includes things that are out of the Departments of Corrections’ control, such as Town Clerks’ days or hours of operation, how mail is routed for delivery, the back-and-forth mailing of documentation that is sometimes necessary to resolve registration issues or ballot address disputes. As noted by one Vermont stakeholder, incarcerated residents “move around so much and their mail does not necessarily follow them, and ballots won’t follow them.”

…those extra extra hoops to jump through with mailing and making sure it’s mailed on time and getting it back and getting it mailed again on time. So I think that’s one of the biggest barriers we have. There are several steps to go through.”

– Staff member, Vermont Department of Corrections

In Maine, it is policy to treat outgoing absentee ballots as “privileged mail” or “legal mail.”47 The legal mail designation is important so that documents, like ballots, are handled appropriately (e.g., residents receive all original documents and the full contents of the mailing) and, theoretically, that should ensure timely delivery.48 Based on our discussions with staff and stakeholders, it appears that the mail room also treats incoming absentee ballots as legal mail. While some staff and stakeholders commented that this designation was helpful, one Maine staff member detailed how the legal mail designation might also cause delays:

“If it’s legal mail, which I think the actual ballot counts as, then it’s going to wait until somebody from the mailroom can come stand in front of the resident, open it in front of the resident so they can see it being opened because they still have to check for contraband…go through it without reading it, and then give to the resident. And that’s not something that necessarily can get done every day. But everything has to get processed here…so everything is taking a little bit longer in here.”

A lack of clarity about classification of incoming voter mail raises concerns for the potential of staff to mishandle certain incoming voter forms. For example, one Maine incarcerated resident noted that, “I’ve been given my ballot but not the envelope it’s supposed to be mailed back in. Some training for prison staff would help.”

Anything that it takes on the outside mail-wise, it’s going to take at least twice as long for somebody who’s incarcerated.”

– Staff member, Maine Department of Corrections

Each step of the process adds additional time. Mail delays and the mishandling of mail mean an incarcerated resident may ultimately not be able to vote, or have their vote counted, if their ballot arrives after the prescribed deadline.

Capacity limitations influence the implementation of voting in prisons. Both Departments of Corrections are certainly not immune to staffing shortages.49 In our discussions with staff and stakeholders, a consistent throughline in both states was the level of capacity and person-power – there never seemed to be enough. Demands on government agencies, such as the Secretary of State’s Office, ebb and flow. Civic and non-profit organizations, as well as individual volunteers, also face capacity issues. For voting rights work, and especially time-sensitive in-person registration events and voter educational outreach, this means that capacity issues matter. Due to the sheer number of incarcerated people and the number of facilities in each state, there is not enough person-power to ensure all incarcerated residents have the same access to services that support their right to vote.

- External partners may not be able to assist with in-person registration events for every election cycle; if they are able to do so it may be only for a limited number of facilities. Voter registration events may also be limited in size and scope, depending on security needs and the number of personnel (internal or external) available to assist.

- Staff and stakeholders may have limited capacity to liaison between Town Clerks and incarcerated voters to address any registration or ballot issues (e.g., use of full legal names, such as including Jr. or II, verifying last known addresses, paperwork to forward resident’s ballots if they change location).

All of these constraints may inadvertently create inequity in voting rights access across different facilities. While some incarcerated residents may potentially receive the help they need, other incarcerated residents may not receive the same opportunities and access to voting as their peers.

Part 5: Recommendations

The United States continues to be an international outlier due to the sheer number of people stripped of their voting rights as a result of a felony-level conviction.50 The states of Maine and Vermont should be applauded for their historic enshrinement of voting rights for all its citizens.

For incarcerated citizens who can vote – those with misdemeanor convictions or awaiting resolution of their charges but also those completing felony-level sentences as in Maine and Vermont – the United States also lags behind other countries in providing access to voting. Many countries, such as Chile, Croatia, and the Netherlands, have removed logistical barriers to voting by including polling stations within their prison system.51 In the United States, Cook County (Chicago, Illinois), the District of Columbia, and Harris County (Houston, Texas) have been successful in establishing polling stations inside jails – facilities where transitions from incarceration to release happen much more quickly compared to prisons.52 Given the extent of mass incarceration in the United States, it is especially important to protect democratic rights by disentangling voting rights from criminal sanctions.

The logistical complexities of voting while in a prison environment are significant, but upholding our democratic commitment to an inclusive and representative government is worth the investment to improve voter education and voting access for everyone. Based on what we have learned from our study of Maine and Vermont, The Sentencing Project offers the following recommendations to advance voting access in our nation’s correctional facilities:

Universal Recommendation: Implement In-Person Voting in Prisons

To truly provide equitable access to voting and democracy, The Sentencing Project advocates for the implementation of on-site polling locations in all prisons and jails where there are eligible voters. Based on our interviews with corrections staff who work in Maine and Vermont, as well as the vast majority of stakeholders who support voting rights work, there is support to reimagine how incarcerated residents vote – to make in-person voting a reality within the facilities.53

- “If we wanted to reduce barriers, [by] having in-person polling stations I think we would increase our turnout dramatically…There wouldn’t be those extra extra hoops to jump through…” – Staff member, Vermont Department of Corrections

- “I think on voting days, somebody should be running a voting station in here. This is a community, right?” – Staff member, Maine Department of Corrections

In Maine and Vermont, the majority (65%) of survey respondents stated they would like the option to vote in person.54 Incarcerated residents commented on how having on-site voting would make it easier for them to vote.

All Departments of Corrections should consider affirmatively supporting legislation and any policy that permits on-site polling locations at correctional facilities. Incarcerated people should have the opportunity to vote in person.

Recommendations for Developing Institutional Policies and Practices for Departments of Corrections Leadership and Staff

(1) Create an official voting rights policy and a corresponding staff guidance document on voting rights work in all Departments of Corrections.

Create a stand-alone institutional-wide voting rights policy that affirms, or reaffirms, incarcerated residents’ right to vote, making clear that they do not lose their right to vote upon incarceration. A voting rights policy should also be included in all facility-level handbooks and orientation packets distributed to incarcerated residents.

A staff guidance document should formally outline staff roles and responsibilities in relation to voting rights work, increase efficiency of time that staff allocate to duties, create staff understanding of when and how voting rights work is to be conducted throughout the year and during election cycles, inform decision-making resulting in improvements to the voting rights work, and increase consistency across facilities.

Policies and guidance help create institutional knowledge, assist when training new staff, and guide supervisor and staff decision-making.

(2) Create opportunities for all-staff education on incarcerated residents’ voting rights and the basic process of assisting incarcerated residents who are voting from correctional facilities.

While particularly relevant for corrections staff tasked to execute this duty, all staff can benefit from learning how to assist incarcerated residents exercise their right to vote. These learning opportunities can be merged with events for incarcerated residents (e.g., orientation, voter education opportunities), but also included in new hire training and continuing education programs so that all staff have baseline knowledge. In Maine and Vermont, the imperative, baseline knowledge for all staff starts with a firm understanding that incarcerated residents retain their right to vote. Their training should go on to include an overview of voting policies and guidance documents, as well as how to help incarcerated residents when they inquire about voting. Such continuing education would also increase the number of staff who can serve as points of contacts for partner agencies and volunteers who help facilitate registration and ballot access.

Tailored training opportunities should be given to staff with voting rights duties. This training can be offered by a partner agency (e.g., Secretary of State) with expertise. This will result in designated staff (e.g., volunteer services coordinators, case managers) having the knowledge on how to assist incarcerated residents to register, update their voter registration, request absentee ballots, and return completed ballots. This is particularly relevant if staff are allowed to help incarcerated residents register online using state-run online registration websites.

(3) Create, formalize, and strengthen working relationships with voting rights partners across government agencies and other organizations.

Voting rights staff or designees should take an active role in cultivating and maintaining relationships with helpful external and internal partners. The Secretary of State’s Office, local chapters or branches of the League of Women Voters and the NAACP, Disability Rights offices, incarcerated resident-led groups, and other non-profit groups and volunteers, can assist with in-person voter registration drives and other processes, including innovations related to voting while incarcerated. These working relationships can help to streamline workflows that would help incarcerated residents and external partners address errors and corrections on voting rights forms. As suggested by one stakeholder, having more than one staff member as a point of contact speeds up the efficiency in correcting any errors on voting forms.

External agencies are not always aware of incarcerated residents’ limited access to the internet or the additional steps needed to navigate the voting process. Through better information-sharing among corrections staff and other agencies and partners, innovations may evolve that streamline the voting process during incarceration. It may also help to ease the workload (e.g., automatically being sent registration forms during election years without the need to request them).

Recommendations to Assist Incarcerated Voters with the Voting Process

(1) Increase education for incarcerated residents about their voting rights and how to vote.

We recommend leveraging partnerships with external and internal stakeholders who work with justice-impacted individuals and understand the many complexities of voting while incarcerated.

- Provide information about the residents’ right to vote at multiple touchpoints. For consistency, require informing all incarcerated residents about their voting rights during their intake process and orientation. Add additional touchpoints during case management sessions to remind incarcerated residents they can vote while they are incarcerated. Be sure to include information about voting rights in written policy and other documentation, like residents’ handbooks.

- Conduct quarterly voting rights informational sessions while concurrently providing more registration opportunities.55 Offering these general information sessions about voting and how to vote in one’s jurisdiction would give staff and voting rights partners four touchpoints throughout the year to register interested voters. As well as discrediting the misperception that incarcerated residents cannot vote, the goal would be to increase overall understanding of the voting process. Because in-person registration drives close to an election may not have the capacity to serve all interested incarcerated residents, distributing this work throughout the year may alleviate capacity and access concerns.

- Introduce “absentee ballot clinics” during election cycles. Following in-person registration drives, these clinics would help incarcerated residents learn what to do after they register to vote and receive help, if needed, to request their ballot. This will assist with closing any information gaps about the steps that must be taken between registering and casting a ballot (e.g., completing a ballot request form, addressing any Town Clerk challenge letters, etc.). Consider updating voting guidance documents to reflect this requirement.

- Introduce more opportunities for education about subjects like government and voting. Incarcerated residents who responded to the survey indicated that classes or other programming would be very helpful. A corrections staff member suggested using recordings that could be uploaded to tablets and made freely available to incarcerated residents. To this end, one might inquire if the in-state League of Women Voters or another partner organization would be able to make one or more such videos for incarcerated residents.

- Train incarcerated residents to be peer mentors so that they can offer assistance to other incarcerated residents who would like to vote, or learn about voting. As suggested by a staff member, incarcerated residents who are peer mentors could be a good resource to assist incarcerated residents with voter education. Peer-to-peer mentoring could play a crucial role in helping first-time voters navigate the voting process.

(2) Increase access to candidate information and voter referendum information.

- Aim to host one candidate forum each election cycle. Incarcerated residents’ survey responses strongly indicate there are not enough avenues for them to learn about candidates. Hosting a candidate forum would be a powerful way to increase education about an upcoming election.56 If permissible, these could be recorded and shared on tablets.

- Ensure access to permissible media without additional fees. National newspapers, regional and local newspapers, and other permissible publications should be widely available, and available electronically. Incarcerated residents should be able to access news media on their tablets without incurring surcharges.

- Allow nonpartisan candidate guides created by external partners to be available as hardcopy and on tablets during election cycles. While state-dependent, various organizations create voter guides for residents. In our work, we have come across such guides created by the Secretary of State’s Office and Disability Rights Vermont. These should be easily accessible to incarcerated residents.

Recommendations to Minimize Additional Logistical Challenges to Voting from Correctional Facilities

(1) Increase access to voting forms.

- Make more widely accessible the forms needed to register to vote. Staff members should stock an easily accessible supply of blank voter registration forms at each facility. Forms can be provided in shared communal spaces, including in any existing libraries and classrooms. New residents should receive a voter registration form in their orientation materials.

- During in-person voter registration drives, permit approved external partners – such as representatives from the in-state Disability Rights office or the Secretary of State’s Office – to use their work laptops or an assigned Department of Corrections computer to register voters online and request ballots if such services are available. This would help alleviate some of the logistical barriers and steps for incarcerated residents (i.e., the back-and-forth of mail). It also permits stakeholders to check on voter registration status, mailing addresses, and so on, in real time.

(2) Create a simplified calendar that clarifies timelines and due dates.

This is relevant for requesting or submitting registration forms, requesting an absentee ballot, and guidance on when completed absentee ballots are required to be received by the Board of Elections or Town Clerk’s office.

(3) Leverage the use of tablets at no cost to incarcerated residents.

Within policies and staff guidance documents, in addition to hard copies, permit and encourage staff to use tablets for sharing information on voting rights and voting events with incarcerated residents. Make available electronically any voting materials provided by external organizations (e.g., Disability Rights offices, Secretary of State’s Office, League of Women Voters). Tablets can also be used to send incarcerated residents reminders about deadlines and due dates for voter forms and ballots. Incarcerated residents should not have to pay to access voting rights information on their tablets.

(4) To address mail delays and the unpredictability of the mail system, if such services are available, allow incarcerated residents the option to register to vote online, and also to request and track their ballot online.57

Access could be permitted through tablets with appropriate security settings, as well as implementing security settings on any other computers permitted for use (e.g., for education, law library). As an example, in Maine, the Department of the Secretary of State has valuable and relevant information on their website, including pages such as a voter lookup service, an absentee ballot request status tracker, and the listing of municipal clerks and registrars that helps incarcerated residents find their Town Clerk.58 Allowing incarcerated residents to use an official government website for voter-related tasks like registration mirrors what one would do if they were living in the community. Such normalizing prosocial behavior is a core principle of the Maine Department of Corrections.59 Assistance with online registration and other voting-related tasks could occur during in-person registration drives, absentee ballot clinics, and other informational voting rights events.

(5) Design internal mail policies for voting rights materials that ensure speed of delivery, have the status of legal or privileged mail, and outline proper staff handling of voting rights/legal mail.

Ensuring residents get their voting-related materials in a timely manner is of utmost importance. Establishing policy that directs staff to prioritize distribution of voter materials during election cycles would help speed up the traditional absentee voter process. The policy should make clear for both staff and incarcerated residents which voting materials are classified as legal mail. We advocate for registration forms, ballot requests, and ballots to be designated as legal mail. At minimum, ballots should be considered legal mail. The documents should not be photocopied. Staff working in the mail room must be kept up-to-date on the legal mail classification for voting forms, as well as how to handle those documents in line with security protocols and legal mail classification.

Methodology

Data sources: This report is based on our analysis of three data sources: interviews with 10 Departments of Corrections staff, 11 interviews with stakeholders who collaborated with the Departments of Corrections to implement voting, and a survey of 132 incarcerated residents. The survey data collection process differed between Maine (mailed survey) and Vermont (in-person survey), as described below, based on our agreements with each Department of Corrections. Interview and survey participation was voluntary and participants gave their informed consent. We also conducted an analysis of both states’ Department of Corrections policies and procedures that were publicly available.

Maine: Interviewees included five Department of Corrections staff and five stakeholders. The interviews were conducted from August 2023 to January 2024. The resident survey data were collected from January to June 2024. The Sentencing Project coordinated the survey data collection with a Maine Department of Corrections facility. The surveys were mailed to the facility in January 2024 and returned to The Sentencing Project in June 2024. The facility’s mail room and associated staff members distributed the survey based on a list of qualified residents – 443 residents qualified to participate, because they had been incarcerated during one prior election cycle. Based on a Department of Corrections recommendation, the survey was also distributed to four civic groups of which incarcerated residents are members or leaders: the American Legion, an NAACP prison branch, Incarcerated Veterans of Maine, and the Long-Timers group. Thirty-four residents completed the survey yielding an approximate 8% response rate.

Vermont: Interviewees included five Department of Corrections staff and six stakeholders. The interviews were conducted from November 2023 to May 2024. The residents completed the survey in May 2024. The lead researcher collected the survey data in person at a Vermont Department of Corrections facility over the course of one day. As per the agreement with the Vermont Department of Corrections, every incarcerated person at the facility was deemed eligible to participate. Because of this, we asked an additional question on the Vermont survey to query if participants had been incarcerated during a prior election. With assistance of three Department of Corrections staff members, two incarcerated residents who were peer mentors, and a Disability Rights Vermont staff member, we went to most units in the facility (forgoing the mental health unit, prioritizing the environmental stability of those residents). Surveys were left with a staff member in case a resident wanted to participate after physical data collection ended. Of the 276 possible respondents, 98 residents completed the survey yielding an approximate 36% response rate.

Method of analysis: We analyzed the interview data with the purpose of identifying and isolating recurrent themes and patterns pertaining to facilitators and barriers to voting that spanned across the interviews. We calculated percentages to analyze and summarize the close-ended responses from the incarcerated resident survey. In some instances, we calculated bivariate statistics to isolate significant factors that influenced whether an incarcerated resident voted. The survey also provided incarcerated residents opportunities to elaborate on their answers to the close-ended questions (e.g., “Have you voted since being incarcerated? Yes or No. Please explain why you have or have not voted.”) as well as several open-ended questions (e.g., “What would make it easier to vote while you’re incarcerated?”). We used the same qualitative data analysis approach as used for the interviews to identify recurrent themes in the open-ended prompts.

This study received Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval from Advarra (Pro00070654), which is accredited by the Association for the Accreditation of Human Research Protection Programs, and Vermont’s Agency of Human Services Institutional Review Board.

| 1. | Vermont’s Department of Corrections is a unified system which means that jails and prisons are integrated versus being separate entities. In Maine, prisons and jails are separate entities. We use the term prison throughout the report for consistency, but denote this difference in the structure of their Departments of Corrections. U.S. citizens of Puerto Rico and Washington, DC also retain their right to vote while completing a sentence for a felony-level conviction. Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Dole, J. R. (2024, December 30). Illinois bill would restore voting rights to thousands of incarcerated people. Truthout; Levi, G. (2025, April 21). Maryland must end felony disenfranchisement. The Baltimore Sun; Selsky, A. (2023, March 09). Oregon looking at allowing people in prison to vote. Associated Press. |

| 3. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project. |

| 4. | Porter, N. D., Parker, A., Walk, T., Topaz, J., Turner, J., Smith, C., LaRonde-King, M., Pearce, S., & Ebenstein, J. (2024). Out of step: U.S. policy on voting rights in global perspective. The Sentencing Project, Human Rights Watch, & the American Civil Liberties Union. |

| 5. | In addition to the 1,034,995 individuals who cannot vote in prison while completing a sentence for a felony-level conviction, an additional 118,653 individuals in our nation’s jails are also barred from voting while completing a felony-level sentence. In total, an estimated 4,049,978 U.S. citizens cannot vote due to a felony-level conviction. The remainder of individuals barred from voting are either on community supervision (1,279,893) or post-sentence (1,616,437). Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 6. | Nellis, A. (2021). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | “Other stakeholders” referred to here are not Department of Corrections employees. They represent a wide variety of people – ranging from those who work in government offices, to nonprofits, to individual volunteers – who support voting rights work in prisons by working with or coordinating with the Department of Corrections. |

| 8. | Nguyen, A., & White, A. (2021). Locking up the vote? Evidence from Maine and Vermont on voting from prison. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1086/714927; White, A., & Nguyen, A. (2022). How often do people vote while incarcerated? Evidence from Maine and Vermont. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 568-572. https://doi.org/10.1086/714927 |

| 9. | Nguyen, A., & White, A. (2021). Locking up the vote? Evidence from Maine and Vermont on voting from prison. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1086/714927; White, A., & Nguyen, A. (2022). How often do people vote while incarcerated? Evidence from Maine and Vermont. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 568-572. https://doi.org/10.1086/714927 |

| 10. | In jails, individuals who are pretrial or completing misdemeanor-level sentences do not lose their right to vote and, therefore, can participate in elections. To learn more about jail-based voting, see Rosewood, A., & Wang, T. (2024). Laws that govern jail-based voting: A 50-state legal review. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation: Harvard Kennedy School; Wang, T. (2024). Jail-based voting in Denver: A case study. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation: Harvard Kennedy School. |

| 11. | Zeng, Z. (2025). Jail inmates in 2023 – Statistical tables. Bureau of Justice Statistics. |

| 12. | Sabino, P. (2022, July 12). Cook County jail detainees had a higher voter turnout in the primary than the city as a whole. Block Club Chicago; Woods, M. P. (2024, October 12). Incarcerated voters turn out for June 4 primary. League of Women Voters of the District of Columbia. |

| 13. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 14. | Nellis, A. (2021). The color of justice: Racial and ethnic disparity in state prisons. The Sentencing Project. |

| 15. | See, for example, Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public safety by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project; Wang, T. (2024). Jail-based voting in Denver: A case study. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation: Harvard Kennedy School; Wang, T. (2024). Jail-based voting in the District of Columbia: A case study. Ash Center for Democratic Governance and Innovation: Harvard Kennedy School. |

| 16. | This survey included incarcerated people in prisons and jails. Of the 52,495 incarcerated people who answered their question on party affiliation, 35% identified as independent, 22% identified as Republican, 18% identified as Democrat, and 17% identified as “other.” The remaining 8% of respondents identified more than one affiliation (e.g., independent, other; independent, Republican; independent, Democrat; or some other combination). See, Lewis, N., Heffernan, S., & Flagg, A. (2024). ‘Trump remains very popular here’: We surveyed 54,000 people behind bars about the election. The Marshall Project; The Marshall Project. (2024). The Marshall Project 2024 political survey, state summaries of selected questions. The Marshall Project; The Marshall Project. (n.d.). Journalists: How to report on the political opinions of people in prisons and jails in your state. The Marshall Project. |

| 17. | Porter, N. D., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the right to vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project; Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 18. | Because Washington, DC no longer has its own prison, most residents convicted of a felony-level offense will be transferred to the Federal Bureau of Prisons to complete their sentence. Porter, N. D., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 19. | D.C. Law 23-277. Restore the Vote Amendment Act of 2020. Council of the District of Columbia. |

| 20. | Dole, J. R. (2024, December 30). Illinois bill would restore voting rights to thousands of incarcerated people. Truthout; Levi, G. (2025, April 21). Maryland must end felony disenfranchisement. The Baltimore Sun; Selsky, A. (2023, March 09). Oregon looking at allowing people in prison to vote. Associated Press. |

| 21. | Stakeholders are not Department of Corrections employees. They represent a wide variety of people – ranging from those who work in government offices, to nonprofits, to individual volunteers – who support voting rights work in prisons by working with or coordinating with the Department of Corrections. |

| 22. | Holloway, P. (2013). Living in infamy: Felony disenfranchisement and the history of American citizenship. Oxford University Press. |

| 23. | Holloway, P. (2013). Living in infamy: Felony disenfranchisement and the history of American citizenship. Oxford University Press. |

| 24. | Holloway, P. (2013, pp. 24). Living in infamy: Felony disenfranchisement and the history of American citizenship. Oxford University Press. |

| 25. | Holloway, P. (2013). Living in infamy: Felony disenfranchisement and the history of American citizenship. Oxford University Press. |

| 26. | Demleitner, N. V. (2022). Criminal disenfranchisement in state constitutions: A marker of exclusion, punitiveness, and fragile citizenship. Lewis & Clark Law Review, 26(2), 531-564; ME Const. Art. IX § 13; VT Const. Ch. II § 55; and 28 V.S.A. § 807 (VT 1971) which states “a person who is convicted of a crime shall retain the right to vote by early voter absentee ballot in a primary or general election,” so long as they meet the other voter-eligibility requirements such as residency. |

| 27. | This prevents the harmful process of prison gerrymandering (see, for example, the Prison Gerrymandering Project by the Prison Policy Initiative). The prison address will be used only as the mailing address for the absentee ballot; the voter’s ballot and ballot choices will reflect the contests in their home district. |

| 28. | Nguyen, A., & White, A. (2021). Locking up the vote? Evidence from Maine and Vermont on voting from prison. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1086/714927; White, A., & Nguyen, A. (2022). How often do people vote while incarcerated? Evidence from Maine and Vermont. The Journal of Politics, 84(1), 568-572. https://doi.org/10.1086/714927 |

| 29. | While The Sentencing Project uses person-first language (e.g., person with a felony conviction and incarcerated resident), we have not adjusted the language used by incarcerated individuals in their direct quotes. |

| 30. | Total number of respondents, 127. |

| 31. | Total number of respondents, 127. |

| 32. | 107 of the survey takers were incarcerated during a prior election cycle. The difference between the proportion of residents who understood the voting process amongst individuals who voted (n=41, M=0.927, SD=0.264) and the proportion of residents who understood the voting process amongst individuals who did not vote (n=64, M=0.312, SD=0.467) is statistically significant, t(101)=8.598, p ≤ .000. |

| 33. | Total number of respondents, 123. Many respondents (35%) did not remember when they learned about their voting rights. |

| 34. | Total number of respondents, 123. |

| 35. | Disability Rights Vermont. (n.d.). About DRVT – Disability Rights Vermont. Disability Rights Vermont. “Disability Rights Vermont (DRVT) is part of the National Protection and Advocacy system. This national system was created by Congress in response to concerns that States were not doing enough to protect people with disabilities against abuse, neglect, and serious rights violations. Congress created the Protection and Advocacy (P&A) system to increase scrutiny and available resources to improve conditions for people with disabilities. Each state has a P&A system; some are part of state government and some are private, non-profit corporations. DRVT is a private, independent, nonpartisan, non-profit corporation designated by the Governor to be Vermont’s P&A system, authorized to advocate and protect the legal rights of people with disabilities in Vermont.” |

| 36. | |

| 37. | Vermont Department of Corrections. (2017). Inmate voting policy 324.01. Vermont Department of Corrections. |

| 38. | Vermont Department of Corrections. (2017). Guidance document: Voting. Vermont Department of Corrections. |

| 39. | While The Sentencing Project uses person-first language (e.g., person with a felony conviction and incarcerated resident), we have not adjusted the language used by incarcerated individuals in their direct quotes. |

| 40. | While The Sentencing Project uses person-first language (e.g., person with a felony conviction and incarcerated resident), we have not adjusted the language used by incarcerated individuals in their direct quotes. |

| 41. | Vermont Department of Corrections. (2002). Offender classification policy 371. Vermont Department of Corrections. |

| 42. | Total number of respondents, 125. |

| 43. | Total number of respondents, 125. 72% of respondents said it would be very helpful. |

| 44. | Total number of respondents, 125. 54% said it would be “very helpful” and 26% said it would be “somewhat helpful.” |

| 45. | Vermont Department of Corrections. (2017). Guidance document: Voting. Vermont Department of Corrections. |

| 46. | Vermont Department of Corrections. (2017). Guidance document: Voting. Vermont Department of Corrections. |

| 47. | “Legal mail” generally includes privileged or confidential mail correspondence with lawyers and the courts. Vermont does not have a legal mail designation for absentee ballots. Maine Department of Corrections. (2018). Prisoner mail policy 21.02. Maine Department of Corrections. |

| 48. | See, for example, Lapin, A. C. (2009). Are prisoners’ rights to legal mail lost within the prison gates? Nova Law Review, 33(3), 704-728. https://nsworks.nova.edu/nlr/vol33/iss3/9; Nahra, A., & Arzy, L. (2020). Why mail service is so important to people in prison. Brennan Center for Justice; University of Maine School of Law. (2018, August 15). Maine law student attorneys win cases on the “prisoner mailbox rule.” University of Maine School of Law. |

| 49. | The Marshall Project. (2025). How to investigate prison staffing trends in your state. The Marshall Project. |