Youth Justice by the Numbers

Between 2000 and 2023, youth incarceration fell by almost 75%. However, racial and ethnic disparities in youth incarceration and sentencing persist amidst overall declines in youth arrests and incarceration.

Related to: Youth Justice

Between 2000 and 2023, youth incarceration fell by almost 75%. However, racial and ethnic disparities in youth incarceration and sentencing persist amidst overall declines in youth arrests and incarceration.

Introduction

Youth arrests and incarceration increased dramatically in the closing decades of the 20th century but have fallen sharply since. Public opinion often wrongly assumes that crime (and incarceration) is perpetually increasing. In fact, the 21st century has seen significant declines in both youth arrests and incarceration. Despite positive movement on important indicators, far too many youth—disproportionately youth of color—are incarcerated. Nevertheless, between 2000 and 2023, the number of youth held in juvenile justice facilities, adult prisons, and adult jails fell from 120,200 to 31,800—a 74% decline.

Youth Arrests

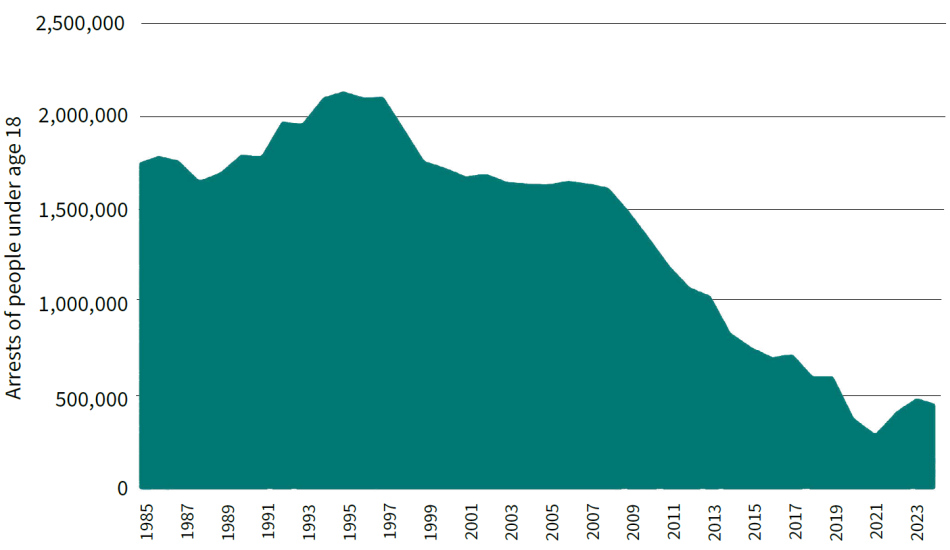

The number of arrests of people under 18 years old peaked in 1995 and has declined more than 75% since. Most youth arrests are for non-violent offenses: in 2024, just 8.5% of youth arrests were for offenses categorized by the FBI as Part 1 violent crimes (aggravated assault, robbery, rape, and murder). Youth arrests increased from 2021 to 2023 (before falling in 2024); the most recent arrest levels remain well below pre-pandemic levels.

Figure 1. Youth Arrests, 1985-2024

Source: Federal Bureau of Investigation (2025). Crime data explorer.

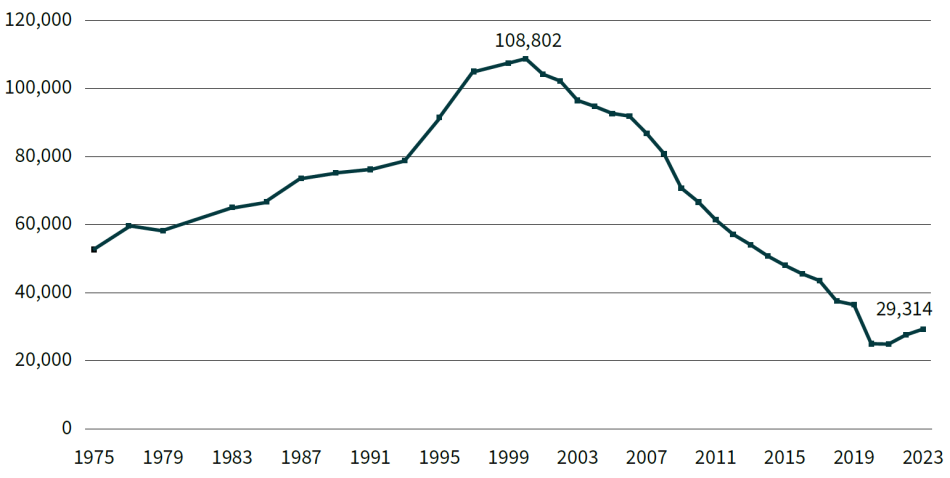

One-Day Count of Youth Incarceration

Between 2000 (the peak year) and 2023, the number of youth held in juvenile justice facilities on a typical day fell from 108,800 to 29,300, a 73% decline, reflecting both declines in youth offending and arrests and reduced use of incarceration for arrested youth. The one-day count of youth incarceration increased from 2022 to 2023, but remains well below pre-pandemic levels.

This one-day count combines figures for two sets of youth. First, it includes those held in detention facilities (those awaiting their court dates or pending commitment to a longer-term facility after being found delinquent in court). Second, it includes committed youth held in youth prisons, residential treatment centers, group homes, or other facilities designed for longer terms of incarceration (as a court-ordered consequence after being adjudicated delinquent in juvenile court). In 2023, 45% of youth in the one-day count were in detention (the juvenile equivalent of being jailed) and 53% had been committed to a secure facility (the juvenile equivalent of imprisonment).1 These counts do not include people under age 18 held in adult prisons and jails.

Importantly, the one-day count understates the scope of youth incarceration, particularly for those who are detained upon their arrest. Youth were admitted to detention and commitment facilities on delinquency offenses roughly 150,000 times in 2022, the most recent year for which data are available. Even this number does not include youth held on criminal charges, for violations of their probation, or for status offenses. By comparison, the one-day count for 2022 was one-fifth that number.

Figure 2. One-Day Count of Youth Held in Juvenile Justice Facilities, 1975-2023

Sources: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, T.J., and Kang, W. (2025). Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement: 1997-2023. National Center for Juvenile Justice. Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2025). Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985-2022. National Center for Juvenile Justice (2024). Juvenile residential facility census databook: 2000-2022. National Center for Juvenile Justice. Sickmund, M. (2023). Residential placement trends, 1975-2019. [Unpublished data, available upon request.]Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement.

Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Youth Incarceration

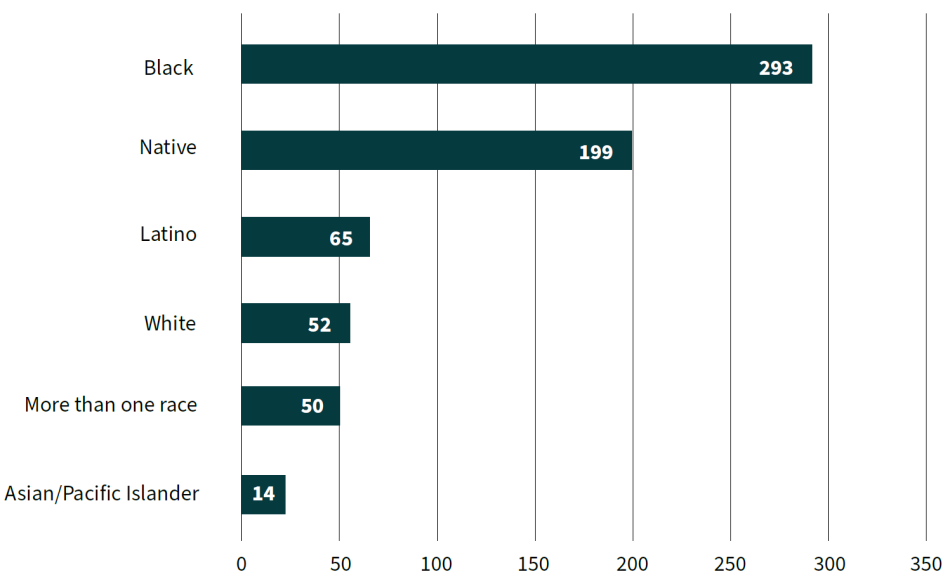

Youth of color are much more likely than white youth to be held in juvenile facilities. In 2023, the white incarceration rate in juvenile facilities was 52 per 100,000 youth under age 18. By comparison, the Black youth incarceration rate was 293 per 100,000, 5.6 times as high. Native youth2 were 3.8 times as high (199 per 100,000) and Latino youth were 25% more likely (65 per 100,000). Asian American youth were the least likely to be held in juvenile facilities (14 per 100,000).

Figure 3. Youth Incarceration Rates by Race and Ethnicity, 2023

Rate per 100,000 Youth

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, T. J., & Kang, W. (2025). Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement. National Center for Juvenile Justice.

| Decision Point | Black Youth | White Youth | Disparity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arrests per 100,000 youth (2020) |

2,487 | 1,080 | Despite modest differences in self-reported behaviors, Black youth are 2.3 times as likely to be arrested as are white youth. |

| Cases diverted from formal processing per 100 juvenile court cases (2022) |

41 | 52 | Among those youth referred to juvenile court for delinquency offenses, white youth are 26% more likely to have their cases diverted. |

| Cases detained per 100 juvenile court cases (2022) |

29 | 19 | Among those youth referred to juvenile court, Black youth are 60% more likely to be detained. |

| Cases committed per 100 juvenile court cases (2021) |

8.7 | 5.3 | Among those youth referred to juvenile court, Black youth are 64% more likely to be committed than white youth. |

Sources: National Center for Juvenile Justice (July 8, 2022). Juvenile arrest rates by offense, sex, and race. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2025). Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985-2022. National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Sources of Black-White Incarceration Disparities for Youth

Disparities in youth incarceration stem both from differences in offending and from differential treatment at multiple points of contact with the justice system. Black youth are more likely to be arrested than their white peers, and then are more likely to receive harsher sanctions as they move through the system. White youth are more likely to be diverted from formal system involvement compared with Black youth. Black youth are more likely to be detained upon their arrest. When found delinquent (i.e., convicted in juvenile court), white youth are more likely to receive probation or informal sanctions, whereas Black youth are more likely to be incarcerated.

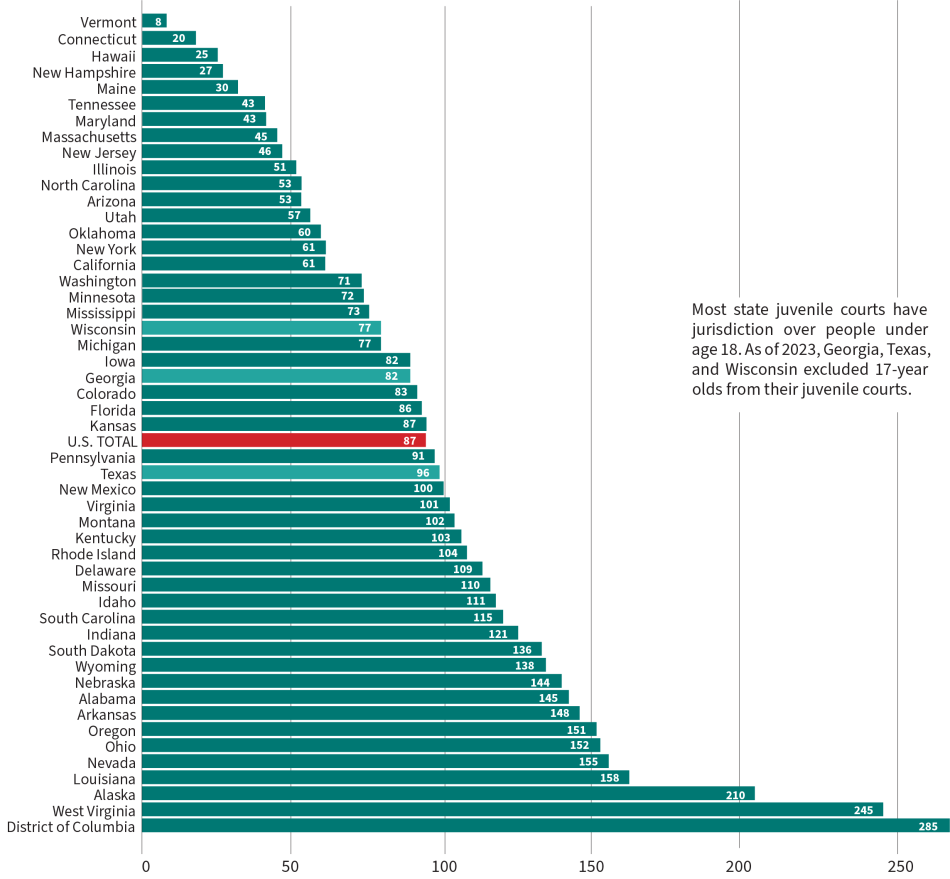

Combined Youth Incarceration Rates by State

On a typical day, 87 out of 100,000 youth nationwide are held in juvenile facilities, pre- and post-adjudication, with rates varying widely among states. The highest youth incarceration rate in 2023 was in the District of Columbia, where 285 out of 100,000 youth were incarcerated in juvenile facilities; the lowest rate was in Vermont, where the rate was 8 out of 100,000 youth.

Figure 4. Youth Incarceration Rate By State (2023)

Incarceration rate for detained and committed youth per 100,000 youth

For the purposes of this graph, youth are defined as age 10 through the maximum age of court jurisdiction in that state.

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, T.J., and Kang, W. (2025). Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement: 1997-2023. National Center for Juvenile Justice.

One-Day Count of Youth in Adult Prisons and Jails

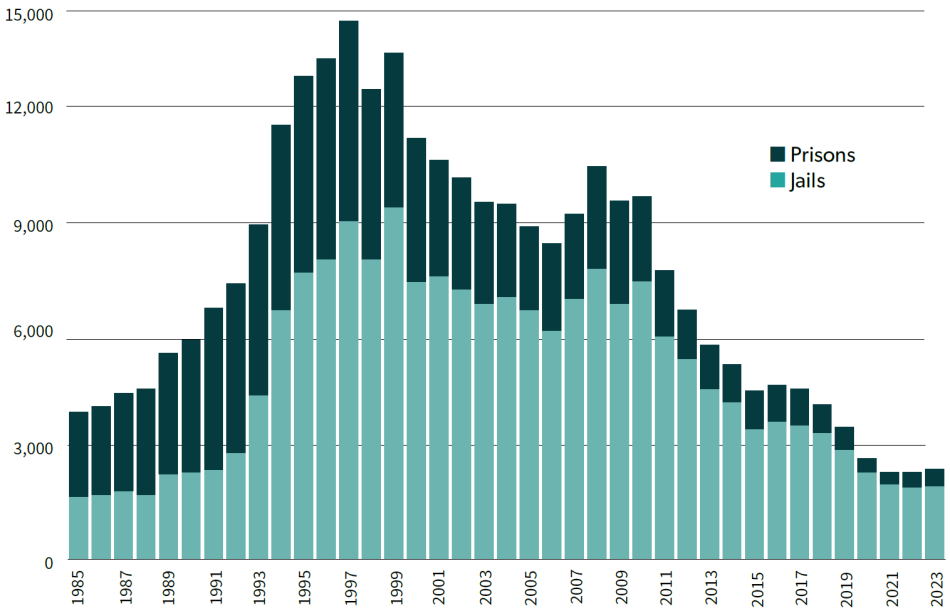

In 2023, 2,000 people under 18-years-old were held in an adult jail and 513 were serving sentences in an adult prison, representing an 83% decline from the peak year, 1997, when 14,500 youth were held in these facilities.3 In 2023, 23 states had no people under 18 in their adult prisons.4

Between 2021 and 2022, there was a notable rise in the number of youth in adult prisons, reflecting a 50% increase in only one year, a trend that continued in 2023. Though this population is small in number, this rise represented a reversal of a 25-year trend.

Figure 5. Youth in Adult Jails and Prisons (One-Day Count) 1985-2023

Sources: Austin, J., Johnson, K., & Gregoriou, M. (2000). Juveniles in adult prisons and jails: a national assessment. U.S. Department of Justice, Office of Justice Programs, Bureau of Justice Assistance; Miller, D. and Kluckow, R. (2023). Prisoners in 2023 – Statistical tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, and prior editions; Zeng, Z. Carson, E.A., and Kluckow, R. (2025). Just the stats; juveniles incarcerated in U.S. adult jails and prisons, 2002–2021. Bureau of Justice Statistics; Zeng, Z. (2025). Jail inmates in 2023 – statistical tables. U.S. Department of Justice, Bureau of Justice Statistics, and prior editions.

Decades of Progress, But Troubling Disparities Remain

The sharp declines in youth arrests and incarceration aligned over the last several decades, and we know that incarcerating fewer adolescents did not lead to increases in youth offending during this time. False narratives around youth crime arguing for so-called “get-tough” approaches have been tried in the past and failed. Common sense approaches that limit incarceration have coincided with increased community safety. Nevertheless, the persistent racial and ethnic disparities in the youth justice system highlight the need to address the sources of those disparities wherever they emerge. Youth incarceration damages adolescents’ well being on multiple dimensions,5 but effective alternatives exist that show lower recidivism and higher life achievement.6

The long-term portrait of youth justice is a promising one: far fewer youth are being arrested and referred to juvenile and adult courts than decades ago. These changes have allowed for the closure of more facilities; additional progress is not only possible, but necessary. Sending youth to the adult system or limiting the use of diversion will not improve outcomes for youth nor communities. Youth who are given informal responses to their offending have better results, and the success of these diversionary programs provides a model for even more states to reduce the footprint of their justice systems.7

Glossary

- Adjudication refers to the juvenile court’s process that determines guilt.

- Detention refers to youth confined upon arrest and before their court disposition. Some youth in detention have completed their judicial proceedings and are awaiting the location of their long-term incarceration. Such youth are generally held in facilities called juvenile detention centers. Youth in detention are suspected of delinquent acts or status offenses (such as incorrigibility, truancy or running away) or are awaiting the result of their court hearings.

- Commitment refers to youth confined in residential facilities after their adjudication. These facilities often have ambiguous names such as training schools, residential treatment centers, or academies.

- This is also called “placement,” a confusing term because “placement” can also refer to all youth held in juvenile facilities, including detained youth. The largest of these commitment facilities, typically state-run, are sometimes informally called “youth prisons.”

- Youth can also be committed to non-carceral facilities, such as group homes, wilderness camps or treatment centers.

- Referral to juvenile court equates to arrest. Juvenile court cases begin with a referral.

| 1. | The remainder are listed as being held for unknown reasons or as part of a diversion program. |

|---|---|

| 2. | The term Native youth refers to people identified by the U.S. Census Bureau as American Indians. For this purpose, Native youth do not include Native Hawaiians, who are counted by the U.S. Census Bureau among Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders. |

| 3. | Counts are as of a single day. The number of people in prison is taken at year end and the number of people in jail is mid-year. |

| 4. | States with no youth in their adult prisons are: Alabama, Alaska, California, Delaware, Hawaii, Idaho, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, Montana, New Hampshire, New Jersey, New Mexico, New York, North Dakota, Oregon, Rhode Island, South Dakota, Vermont, West Virginia, and Wisconsin. |

| 5. | Mendel, R. (2023). Why youth incarceration fails. The Sentencing Project. |

| 6. | Mendel, R. (2023). Effective alternatives to youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: a hidden key to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project. |