Expanding Electoral Engagement Among Justice-Impacted People

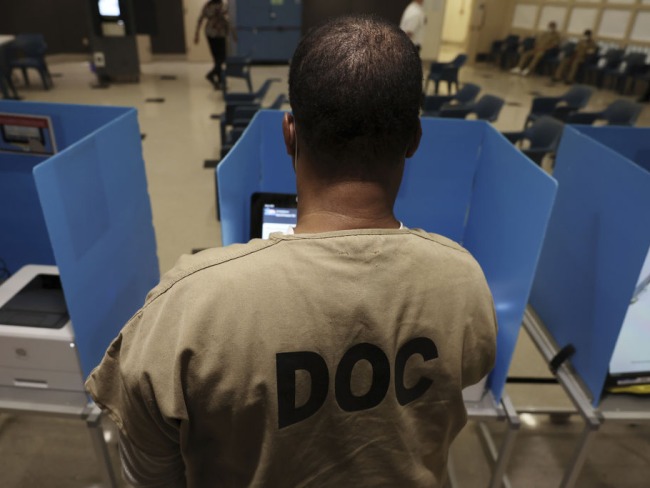

This brief examines the current research and identifies effective strategies used to mobilize justice-impacted communities to vote.

Related to: Voting Rights

Across the country, an estimated 4 million people are disenfranchised due to felony convictions—a decline from an estimated 5.9 million in 2016, thanks to advocacy and policy changes that restored voting rights to people on parole and probation.1

For many justice-impacted people, removing legal barriers to voting is necessary for full participation in democracy, yet eliminating the legal obstacles alone would not be sufficient. Electoral participation2 among eligible voters with felony convictions appears to be very low relative to overall turnout.3 Reasons for this vary, including misperceptions about eligibility, diminished trust in government, and a lack of targeted outreach.

This brief examines the current research and identifies effective strategies used to mobilize justice-impacted communities to vote. Identifying effective strategies to mobilize justice-impacted communities to vote is valuable because it supports inclusive democratic participation and helps ensure that all voices—especially those directly impacted by the criminal legal system —have equitable access to the electoral process. Research teams partnering with community organizations have conducted innovative field experiments in states including Minnesota, Connecticut, North Carolina, Texas, and California.4 The research teams in these studies have overcome the logistical challenges of locating and engaging people with felony convictions, a highly transient and difficult-to-reach group. For example, by linking conviction records with voter registration data, researchers in Connecticut targeted recently released individuals using state-provided contact information for mobilization outreach, while researchers in North Carolina relied on commercial data to reach a broader group of potential voters. These studies have found that simply reaching out and inviting formerly incarcerated people to vote can improve their electoral engagement.

From this body of work, we highlight achievements—such as modest yet meaningful gains in voter registration and turnout following outreach initiatives—as well as ongoing challenges, including barriers to voting and the difficulty of accessing multiple data sets needed to conduct comprehensive research on registration outreach and outcomes.

There are several lessons to be learned from this growing body of research:

- Justice-impacted people can be mobilized to vote. While justice-impacted people hold a broad diversity of political opinions,5 the fundamentals of political mobilization remain: when people have access to the franchise, they vote when they think voting is important, and because someone asked them to. Justice-impacted people are often neglected in outreach efforts by political parties and campaigns – and this is a gap that other organizations interested in building power among justice-impacted people can fill. If justice-impacted people are invited to participate, they will!

- The more personalized the outreach, the better. This is true for most voters. Personalized overtures soliciting participation, especially from people who are respected by the eligible voter, can be very successful. Justice-impacted people may need support in understanding whether they are eligible to vote, and they may also need to be convinced that voting is valuable. Personalized messages from people they respect or love can help meet these goals.

- Organizers, community groups, and academics can conduct research on effective strategies. Conducting research around the effectiveness of an organization’s outreach strategies can be a crucial part of understanding whether resources are being used wisely. This brief seeks to demystify the challenges one may encounter when doing this kind of research — and opens up possibilities for collaboration between researchers and organizers. We hope this brief can inform how nonpartisan nonprofit organizations with limited resources should structure their outreach initiatives more effectively.

Disenfranchisement of people with felony convictions and changes to U.S. laws

In 2024, an estimated 4 million Americans, or about 1.7% of the voting-age population, were deemed ineligible to vote because of state laws disallowing voting by people with felony convictions. Of the 50 United States, felony disenfranchisement laws exist in 48 of them; only Maine and Vermont allow all otherwise-eligible citizens, including currently incarcerated people, to vote regardless of a felony conviction.6 While the number of people disenfranchised due to a felony conviction is large, the tally of those excluded on this basis has declined significantly from nearly 5.9 million people in 2016.7

The bulk of this change is due to advocacy-driven state reforms in recent decades that would expand voting rights to people with felony convictions. Since 1997, the District of Columbia and 27 states have expanded voting rights to people living with felony convictions. These reforms include: restoration of voting rights for incarcerated people completing a felony sentence in Washington, DC; expansion of voting rights to some or all persons on felony probation or parole in 12 states; and increased accessibility for persons seeking rights restoration or elimination of post-sentence “waiting periods” in other states.8 Some states, including Michigan, have also expanded efforts to simplify voter registration processes for people leaving prison.9

Electoral engagement among justice-impacted people

Barriers to electoral participation for eligible justice-impacted people

Removing legal barriers to voting is a necessary but not sufficient condition to full democratic participation among justice-impacted people. Because people have the right to vote does not mean that they will turn out. Baseline participation in elections among eligible voters with felony convictions appears to be very low, meaning that even when people in this group have the legal right to vote, relatively few are registering or turning out to cast a ballot.10

The reasons for low engagement among this group are many. Experiences with the criminal legal system may diminish access to steady employment, housing, and access to the social safety net.11 Likewise, conviction and incarceration increases feelings of alienation and decreases trust in the government and the belief that one’s political voice matters.12 Contact with the criminal legal system can also introduce confusion about voting eligibility.13 Because people with felony convictions are relatively unlikely to vote, they are also overlooked by organizations such as political parties, pro-democracy organizations, and outreach campaigns that traditionally engage in voter mobilization efforts.14 Being actively recruited to vote is among the strongest predictors of actually doing so on Election Day.15 As a consequence of all these factors, researchers estimate that being convicted of a crime is associated with a subsequent 15 percentage point decline in likelihood of voting – and a 25 percentage point decline among people who have served time in prison.16

Pathways to voting for eligible justice-impacted people

Nonetheless, electoral participation among people with convictions is never zero, and a growing group of scholars have begun investigating the conditions under which justice-impacted people take political action. In this vein, researchers have observed that justice-impacted people mobilize around issues that matter to their lives. They vote when candidates campaign around issues that intersect with their experiences with the criminal legal system, such as reforming stop-and-frisk practices in New York City; they protest police brutality; and they organize to advance rights restoration campaigns.17 Justice-impacted people become politically mobilized when they view their own experiences as discriminatory, inhumane, or otherwise unjust. Connecting one’s experiences to a larger narrative of systemic injustice provides something to fight for and people with whom to organize.18

However, researchers still have much to learn about how and when system-impacted people become active voters. Only a handful of studies have tried to understand why and under what conditions people with convictions become active voters. In their groundbreaking study, Yale political science professor Alan Gerber and colleagues partnered with the state of Connecticut to contact recently released individuals who had spent fewer than three years in prison. Researchers sent a randomized group an informational mailer informing them that they were eligible to register and inviting them to do so.19 Similarly, Yale political science professor Allison Harris and her colleagues targeted the full scope of eligible voters with convictions in North Carolina for a similar outreach effort.20 Both of these mailer-based experiments found that simply reaching out, providing information about eligibility and how to register, and inviting justice-impacted people to do so, increased voter registration and turnout.

These studies solved several logistical problems associated with finding and reaching people with convictions. As a group, they are especially transient, and as individuals they are hard to find, which makes it difficult to research on how best to engage them in electoral politics. Generally, drawing on administrative records of conviction status and voter registration, scholars can identify eligible but unregistered potential voters with convictions. In Gerber’s Connecticut study, scholars worked with the state to obtain contact information for their list – which is why they targeted recently released people, since individuals provide the state with an address where they intend to live upon release, even as those addresses become quickly outdated. In Harris’s North Carolina study, researchers went to a commercial data vendor to obtain address information for a much broader swath of potential voters.

Beyond the technical aspects of building an appropriate list, and the straightforward finding that justice-impacted people are responsive to targeted outreach, scholars and advocates are only just beginning to understand how to engage justice-impacted people in electoral politics. Mailers sent by Gerber and colleagues and the Harris team increased registration by only one or two percentage points. However, such improvements are substantively meaningful, since the initial registration rate among previously unregistered individuals was below 10%. Yet more work is needed to understand how to close the participation gap between eligible voters with convictions and their peers without.

Advocacy Spotlight

Robert Tyrone Lilly

Travis County peer support specialist

Former Grassroots Leadership lead organizer for “Fighting Injustice at the Ballot Box”

Brother Rob Lilly served as the lead organizer for Grassroots Leadership, a community-based organization that partnered with an academic team led by Hannah Walker at the University of Texas, to test relational organizing in Texas. Advocating for and organizing justice-impacted people in central Texas and Houston, Grassroots Leaderships uses relational organizing as a mobilization strategy that relies on relationships to newly engage people in politics. Lead organizer Brother Rob Lilly, who is himself formerly incarcerated, helped recruit other justice-impacted people as research captains and to reach out to people in their networks about registering to vote. Brother Rob views the effort to expand voting rights to all people with felony convictions as connected to a longer struggle for civil rights in the United States.

I [take] offense at how persons with felony convictions have been excluded from the electorate… I believe that it is oppressive and is designed to disempower entire segments of our community – particularly, it’s biased against the African American community… so that to me was offensive. Number one, to defend my sense of dignity as a member of this society, as an African American who’s a part of the long history of resistance to erasure from this society, and as a member of the justice-impacted and social justice committed formerly incarcerated population… and I use those words specifically. I’m not just justice-impacted, but I’m a part of the social justice community that’s seeking to undo the harms that have occurred to us as people that have been justice-impacted. And that can best be done when we have a say in how we are governed, who can govern us, and the carceral logic undergirding our exclusion of participation are eradicated.

Emerging research on engaging justice-impacted people

The expansion of voting rights for people with convictions has motivated a wave of innovative research on effective ways to engage justice-impacted people in the electoral process. Below, we highlight three areas of emerging work that will inform future research and outreach efforts.

Researchers at the Minnesota Justice Research Center (MNJRC) found that any contact by voter mobilization organizers led to a modest increase in the likelihood of voting, during a field experiment that tested combinations of mode (text or phone call) and message (justice-oriented or voter education). During the lead-up to the 2022 midterm elections, the MNJRC evaluated the effectiveness of different contact modes and messages, as well as variations in contact frequency, on turnout among justice-impacted people in Minnesota.21 In a follow-up field experiment during the 2024 general election, the team tested whether sending each recipient multiple mailers, as opposed to just one mailer, would lead to higher voter turnout among justice-impacted people. The forthcoming findings should help inform how organizations with limited resources might best structure their outreach.

New research in Texas led by Hannah Walker, associate professor of government at the University of Texas at Austin, examined whether relational organizing – where prospective voters are contacted by a friend or loved one and encouraged to vote – can make a difference in turnout. Preliminary results suggest that encouragements to register and vote delivered by a loved one can be highly effective. In Walker’s study, neighborhood “captains” identified people in their own networks whom they could encourage to vote; the research team then randomly selected people on the list for the captain to contact. By comparing voting behavior across the groups, this research aims to shed light on whether outreach from someone familiar and trusted is more effective than outreach from more distant organizations or strangers. Loved ones can personalize their outreach efforts, helping justice-impacted people to navigate the electoral process and to view voting as a potentially valuable contribution to their families and communities. Relational organizing would thus be a promising approach for mobilizing justice-impacted voters.22

In another area of emerging research that addresses the difficulty of identifying eligible voters, a team led by Naomi Sugie, associate professor of criminology, law, and society at the University of California, Irvine, examined the effectiveness of using preexisting data sources that organizations have access to, such as mailing or membership lists.23 This research tests various outreach strategies within these existing networks, comparing groups who receive particular types of contact to those who do not. Although use of an existing mailing list is limited by the scope of the list, preliminary findings from this ongoing study demonstrate how organizations can effectively test methods, modes, and messages by randomizing within their lists to find what works best for them.

Challenges in research

There are many reasons for the dearth of knowledge concerning the conditions under which justice-impacted people turn out and vote, including the difficulty of accessing relevant data sets of justice-impacted people, cross-matching such data sets with voter files, and measuring impact since successfully matching the corresponding records can be difficult or time-consuming. What follows is a discussion of these challenges and guidance on how to navigate them, based on research conducted to date.

Accessing relevant data

The first major hurdle that researchers must overcome is the development of a credible and unbiased sample within which to test the effectiveness of a given mobilization strategy. Difficulties in accessing relevant data can be a major impediment for researchers or organizations who want to evaluate the effectiveness of different outreach strategies targeted toward justice-impacted people. To complete the kinds of field experiments similar to those fielded by research teams in Connecticut and North Carolina, three different kinds of data are required: (1) records of people’s involvement with the criminal legal system, to identify a relevant sample, (2) contact information for each person, and (3) voter registration records, to evaluate whether a strategy was ultimately effective. Bulk criminal justice records can be difficult to obtain as every state makes its own determination as to what data can be made available, the quality of that data, and the costs associated with obtaining data. Nearly 40 states require payment of a fee to obtain statewide voter files, which can range from a few dollars to tens of thousands of dollars in states such as Alabama and Wisconsin.24 Additionally, states vary their requirements and rules as to what is contained in voter registration records and who can access those records. To obtain potential voters’ contact information so organizers can reach out and encourage them to participate, the most common approaches are to (1) work with the state, which may have a record of last known address, or (2) purchase contact information from a data vendor, which is another cost that pushes these sorts of projects out of reach for many researchers.

An alternative that is potentially more cost-effective than reliance on administrative criminal justice records is leveraging existing data sources, such as membership lists or mailing lists. An organization that serves self-identified justice-impacted people and has a membership list likely has contact information that can be used for outreach and mobilization.25 However, if the goal is to evaluate strategies for engaging the broader justice-impacted population beyond those who may be members of a given organization, researchers should seriously consider the degree to which an organization’s membership is representative of the overall justice-impacted population. If, for example, members of a specific organization are already significantly more likely to be politically active than non-members in general, then the results of using this approach may be less informative. Both groups — those contacted by researchers and those not contacted — would have high turnout rates, which would make the effectiveness of the strategy appear minimal or perhaps even nonexistent. But the strategy being tested might actually be effective for the broader justice-impacted population, which tends to be less politically active.

Measuring impact across messy data sets

A second major hurdle is that research projects evaluating political mobilization efforts must eventually measure whether those efforts affected behavior: did targeted individuals register or vote following the implementation of the study? To quantify these outcomes, researchers must link their study sample to the post-election voter file, by matching their sample to voter files obtained from the state. Difficulties associated with the matching process abound. Over time, individuals might have used different versions of their name, such as when they signed up with an organization, when they registered to vote, and when they were arrested. They may have omitted or altered their birth dates (an especially common tactic among people who are concerned about revealing their information to the state or other organizations).26 They may have changed their names altogether between the time that they were convicted of a crime and the time that they registered to vote. To complicate matters further, voter files in many states limit the public availability of some voter information, and might only provide a voter’s birth year, but not month or date. Because these data sets do not contain shared individual identifiers, to ensure they are correctly matching the same individuals across sources, researchers must carefully design their linking strategies with extreme care.27

Alternative research approaches and limitations

Researchers have taken alternative approaches to learning about the political lives of justice-impacted people. These include surveys, where individuals can self-report both their experiences with the criminal legal system and their level of political involvement. Social science surveys are not well-suited to developing a robust sample of justice-impacted people, who are, as previously noted, a hard-to-reach and transient group, and not every respondent is willing to reveal their experiences with the criminal legal system to an interviewer. Researchers might also identify justice-impacted people through other recruitment methods and then conduct in-depth interviews with them, to learn about their political orientation, a method that can provide insight into individuals’ motivation for political action; however, this would raise questions about the generalizability of the information to the broader justice-impacted population. Despite sources of bias involved in non-experimental approaches, such designs can still provide useful insight that scholars can build on in future studies. Random selection into the sample and the treatment group is a key strategy to mitigate such biases, and field experiments are the gold standard for developing generalizable knowledge regarding how to get justice-impacted people to vote.

Even as more states expand access to the right to vote for people with felony convictions, turnout among this group remains terribly low. As scholars have only begun examining how to improve engagement among people who are justice-impacted, this research into the question of how and when justice-impacted people are electorally mobilized will help inform future efforts by community organizations and researchers in this field.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Electoral participation refers to the range of activities by which eligible citizens engage with the electoral process and political life in a democracy. Activities include voter registration and enrollment, voting, and pre and post election civic engagement including candidate forums, election monitoring, advocating for improved voting laws. |

| 3. | For example, in her analysis of the 2008 presidential election in five states, Traci Burch estimated turnout among formerly disenfranchised people ranged from 11% in Florida to 35% in Michigan, Burch, T. (2011). Turnout and party registration among criminal offenders in the 2008 general election. Law & Society Review, 45(3), 699-730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2011.00448.x |

| 4. | We discuss work in these states while acknowledging research efforts in a number of other states including New Jersey and Florida. See: White, A., Walker, H.L., Michelson, M. & Roth, S. (2025). Getting out the (newly-enfranchised) vote: Encouraging voter registration after rights restoration. Polit Behav. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11109-025-10055-1 |

| 5. | The Marshall Project (2024). Journalists: How to report on the political opinions of people in prisons and jails in your state. |

| 6. | The District of Columbia and Puerto Rico also do not disenfranchise people due to felony convictions. See: Porter, N.D., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project; Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., Stewart, R., & Hauf, M. (2024). Locked out 2024: Four million denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

| 8. | Twenty-six state changes are documented by Porter, N. D. and McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. Nebraska ended a two-year waiting period for people who have completed their sentence in 2024. See: The Sentencing Project. Nebraska Supreme Court upholds law restoring voting rights to thousands. October 16, 2024. |

| 9. | |

| 10. | Burch, T. (2011). Turnout and party registration among criminal offenders in the 2008 general election. Law & Society Review, 45(3), 699-730. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-5893.2011.00448.x. |

| 11. | Pager, D.(2003). The mark of a criminal record. American Journal of Sociology, 108(5), 937-975. https://doi.org/10.1086/374403; Bryan, B. (2023). Housing instability following felony conviction and incarceration: Disentangling being marked from being locked up. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 39(4), 833-874; Morgan, A. A., Kosi-Huber, J., Farley, T. M., Tadros, E., & Bell, A. M. (2022). Felons need not apply: The tough-on-crime era’s felony welfare benefits ban and its impact on families with a formerly incarcerated parent. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 32(2), 613-625. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-022-02400-3. |

| 12. | Weaver, V. M., & Lerman, A. E., (2010). Political consequences of the carceral state. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 817-833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000456. Uggen, C., & Stewart, R., (2015). Piling on: Collateral consequences and community supervision. Minnesota Law Review, 271. |

| 13. | Caleb Bedillion (2024, Oct. 19). Voting rights confusion keeps formerly incarcerated people from casting ballots. The Marshall Project. |

| 14. | Owens, M. L. (2014). Ex-felons’ organization-based political work for carceral reforms. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 651, 256–265. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24541705. Owens, M. L., & Walker, H. L. (2018). The civic voluntarism of custodial citizens: Involuntary criminal justice contact, associational life, and political participation. Perspectives on Politics, 16(4), 990-1013. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592718002074 |

| 15. | Rosenstone, S. J., Hansen, J. M. (1993). Mobilization, participation, and democracy in America. Singapore: Macmillan Publishing Company. |

| 16. | Weaver, V. M., & Lerman, A. E., (2010). Political consequences of the carceral state. American Political Science Review, 104(4), 817-833. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055410000456. |

| 17. | Laniyonu, A. (2019). The political consequences of policing: Evidence from New York City. Political Behavior, 41(2), 527-558. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48688466. Walker, H. L. (2020). Targeted: The mobilizing effect of perceptions of unfair policing practices. Journal of Politics, 82(1), 119-134. https://doi.org/10.1086/705684. OWENS, M. L. (2014). Ex-felons’ organization-based political work for carceral reforms. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 651, 256–265. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24541705. |

| 18. | Walker, H.L. (2020). Mobilized by injustice: Criminal justice contact, political participation, and race. Oxford University Press. |

| 19. | Gerber, A. S., Huber, G. A., Meredith, M., Biggers, D. R., &, Hendry, D. J. (2015). Can incarcerated felons be (re) integrated into the political system? Results from a field experiment. American Journal of Political Science, 59(4), 912-926. |

| 20. | Harris, Allison, Walker, Hannah, White, Ariel, Doleac, Jennifer, Eckhouse, Laurel, and Foster-Moore, Eric. Working Paper. “Registering Returning Citizens to Vote: A Field Experiment in North Carolina.” https://bpb-us-e1.wpmucdn.com/sites.mit.edu/dist/1/1008/files/2025/05/RegisteringReturningCitizens_JOPaccept_May2025forweb.pdf. |

| 21. | Cunningham, K. R., Galvez, F., & Stewart, R. (2024). From the block to the ballot 2.0. Minnesota Justice Research Center; Kika, T., Stewart, R., & Cunningham, K. R. (2023). From the block to the ballot: Exploring best practices in mobilizing formerly disenfranchised voters in Minnesota. Minnesota Justice Research Center. |

| 22. | Full study is not yet available, but preliminary public results are available from Grassroots Leadership (2025): Fighting Injustice: At the Ballot Box. |

| 23. | Sugie, N.F., Sandoval, J.R., &, Zhang, I.H. (2024). Accessing the right to vote among system-impacted people. Punishment & Society, 26(4), 711-731. https://doi.org/10.1177/14624745241230199. |

| 24. | National Conference of State Legislatures (2025). Access to and use of voter registration lists; U.S. Election Assistance Commission (2020). Available voter file information; Alabama Secretary of State. (n.d.). Voter registration information request form. Retrieved July 2025; Wisconsin Elections Commission. (2025). Badger Voters – FAQ. Retrieved July 2025. |

| 25. | Sugie, N. F., Sandoval, J. R., & Zhang, I.H. (2024). Accessing the right to vote among system-impacted people. Punishment & Society, 26(4), 711-731. https://doi.org/10.1177/14624745241230199. |

| 26. | Brayne, S. (2014). Surveillance and system avoidance: Criminal justice contact and institutional attachment. American Sociological Review 79(3) 367-391. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122414530398 |

| 27. | Tahamont, S., Jelveh, Z., McNeill, M., Yan, S., Chalfin, A., & Hansen, B. (2023). No ground truth? No problem: Improving administrative data linking using active learning and a little bit of guile. PloS one, 18(4), https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0283811; Tahamont, S., Jelveh, Z., Chalfin, A., Yan, S., & Hansen, B. (2021). Dude, where’s my treatment effect? Errors in administrative data linking and the destruction of statistical power in randomized experiments. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 37(3), 715-749. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-020-09461-x. |