Massachusetts Should Restore Voting Rights to Over 7,700 Citizens

Massachusetts should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by restoring the vote to its entire voting-age population.

Related to: Voting Rights, State Advocacy, Racial Justice

More than 7,700 Massachusetts citizens are banned from voting in elections due to incarceration for a felony conviction.1 In 2000, Massachusetts disenfranchised this entire population through a constitutional amendment stripping its citizens of their political voice.2 People of color in particular are more likely to be prohibited from voting because of the stark racial disparities in the Massachusetts criminal legal system.

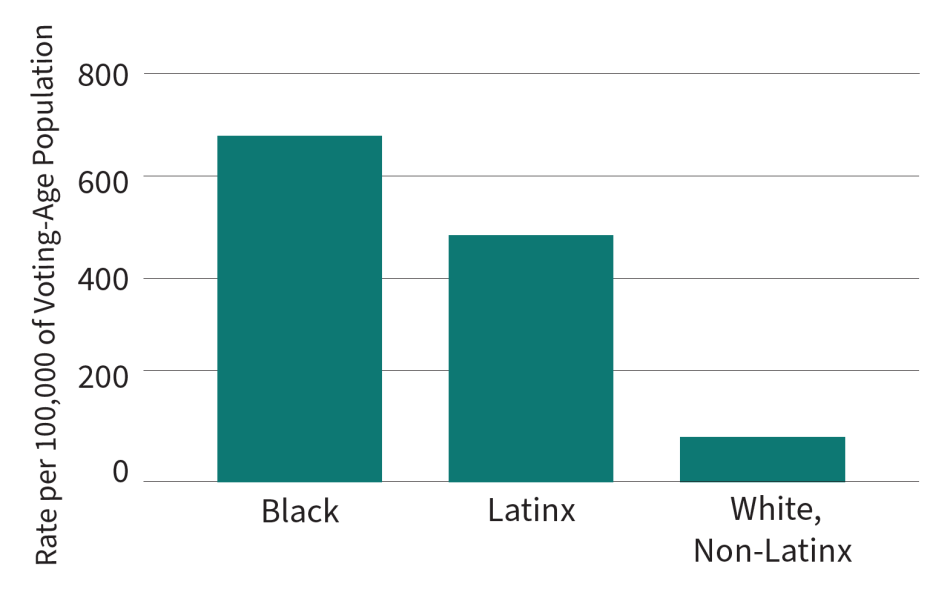

Voter Exclusion Due to Incarceration for a Felony in Massachusetts by Race and Ethnicity, 2022

Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022). Locked out 2022: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project.

Massachusetts’s voting ban results in stark racial injustices in ballot access. Voting-age Black residents are eight times as likely as white residents to lose their right to vote due to imprisonment. The disenfranchisement rate of Massachusetts’s voting-age Latinx population is more than five times that of the white voting-age population.

The law restricting voting for people with felony convictions undermines Massachusetts’s democracy and extends the racial injustice embedded in the criminal legal system to its electoral system. To ameliorate this racial injustice and protect its democratic values, Massachusetts should follow the lead of Maine, Vermont, Puerto Rico, and Washington, DC, and extend voting rights to all citizens, including persons completing their sentence in prison.

Expanding Voting Rights in Massachusetts is a Racial Justice Issue

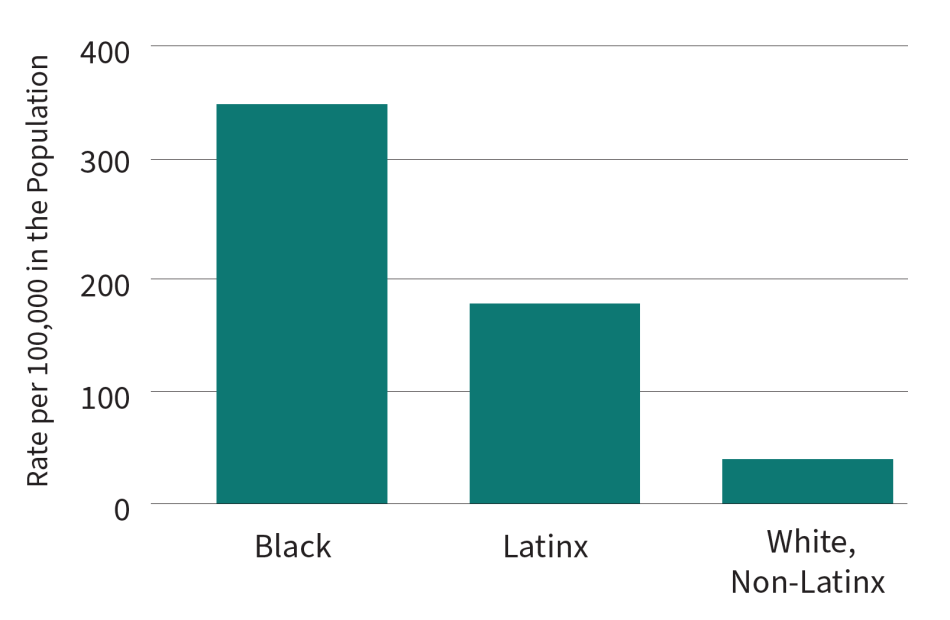

Being denied the right to vote is particularly acute for Black and Latinx residents of Massachusetts due to their disproportionate incarceration. Less than 7% of the state’s population is Black, but 31% of the prison population is Black. Similarly, less than 13% of the state’s population is Latinx, but they make up 29% of the prison population.3

Incarceration in Massachusetts by Race and Ethnicity, 2023

Cannata, N. C., personal communication, November 28, 2023.; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 Census Demographic and Housing Characteristics File (DHC).

Such disparities in incarceration go beyond differences in criminal offending and result from differential treatment throughout Massachusetts’s criminal legal system. The following examples illustrate the disparate effects of these practices on people of color in Massachusetts:

- Policing: Researchers who analyzed data from the Boston Police Department found that neighborhoods in Boston with high percentages of Black and Latinx residents received more Field Interrogation and Observation (FIO) reports (more commonly known as “Stop and Frisk” reports) than neighbors with high percentages of white residents. Estimates showed that a neighborhood with 85% Black residents would generate over 600 more FIO reports in a year than a neighborhood with only 15% Black residents. Racial disparities persisted even when neighborhoods with similar crime rates were compared.4

- Prosecutorial Discretion: Black and Latinx Massachusetts residents were more likely to be sentenced to a state prison than white residents, according to a study by the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School. In comparable cases, prosecutors were more likely to send Black or Latinx defendants to the Superior Court versus white defendants.5 The Superior Courts of Massachusetts are the only courts with the authority to sentence individuals convicted of a felony to a state prison for longer than two and half years.

- Sentencing: An analysis of Massachusetts Department of Corrections data by the Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School found that Black and Latinx defendants charged with weapon or drug offenses were more likely to be sentenced and received longer prison sentences than white defendants even in comparable cases. For example, Black defendants with a weapon offense as their most serious conviction received a sentence 125 days longer on average than white defendants with a weapon offense as their most serious conviction.6

Racial disparity in incarceration is diluting the political voice of people of color in Massachusetts. Massachusetts should safeguard democratic rights and not allow a racially disparate criminal legal system to restrict voting rights.

Supporting Voting Rights Improves Public Safety

Research shows that an opportunity to participate in democracy has the potential to reduce one’s perceived status as an “outsider.” The act of voting can have a meaningful and sustaining positive influence on justice-impacted citizens by making them feel they belong to a community.7 Having a say and a stake in the life and well-being of your community is at the heart of our democracy.

Re-enfranchisement can facilitate successful re-entry and reduce recidivism. The University of Minnesota’s Christopher Uggen and New York University’s Jeff Manza find that among people with a prior arrest, there are “consistent differences between voters and non-voters in rates of subsequent arrest, incarceration, and self-reported criminal behavior.”8 Research also suggests having the right to vote immediately after incarceration matters for public safety. Individuals in states which continued to restrict the right to vote after incarceration were found to have a higher likelihood of experiencing a subsequent arrest compared to individuals in states who had their voting rights restored post-incarceration.9 Given re-enfranchisement misinformation and obstacles facing justice-impacted citizens upon re-entry into our communities, one path to bolster public safety and promote prosocial identities is to preserve voting rights during incarceration.

Allowing people to vote, including persons completing felony sentences in prisons, prepares them for more successful reentry and bolsters a civic identity. By ending disenfranchisement as a consequence of incarceration, Massachusetts can improve public safety while also promoting reintegrative prosocial behaviors.

Massachusetts Can Strengthen its Democracy by Restoring the Right to Vote

Since 1997, 26 states and the District of Columbia have expanded voting rights to people living with felony convictions. As a result, over 2 million Americans have regained the right to vote.10 Massachusetts stands as an outlier. In the late 1990s, incarcerated individuals in one of the state prisons established a Political Action Committee (PAC) to track elected officials’ positions on prison reform and encourage electoral participation among incarcerated voters and their families. Then Governor Paul Cellucci banned the Massachusetts Prisoners Association PAC by executive order and proposed a constitutional amendment to disenfranchise voters sentenced to Massachusetts prisons.11

Massachusetts’s 2000 constitutional amendment severed an entire population’s ability to vote in local and state elections, because they were incarcerated for a felony conviction. In 2001, Massachusetts continued to move in the wrong direction by further restricting voting rights – prohibiting people incarcerated for a felony from voting in federal elections.((Timeline of Massachusetts incarcerated voting rights. (2019, March 10). Emancipation Initiative.)) Yet, Massachusetts has recently shown progress in reversing this racial and social injustice. In 2023, lawmakers introduced numerous proposals to restore the voting rights of people serving a prison sentence for a felony conviction.12 Such proposals should become law.

Massachusetts should strengthen its democracy and advance racial justice by restoring the vote to its entire voting-age population.

| 1. | Uggen, C., Larson, R., Shannon, S., & Stewart, R. (2022). Locked out 2022: Estimates of people denied voting rights due to a felony conviction. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Simmons v. Galvin, US Court of Appeals First Circuit, 08-1569 (2009). |

| 3. | Cannata, N. C., personal communication, November 28, 2023, Massachusetts Department of Corrections.; U.S. Census Bureau, 2020 census demographic and housing characteristics file (DHC). https://data.census.gov/table?q=2020%20census&t=Race%20and%20Ethnicity&g=040XX00US25. |

| 4. | Fagan, J., Braga, A. A., Brunson, R. K., & Pattavina, A. (2015). An analysis of race and ethnicity patterns in Boston police department field interrogation, observation, frisk, and/or search reports. |

| 5. | Bishop, E. T., Hopkins, B., Obiofuma, C., & Owusu, F. (2020). Racial disparities in the Massachusetts criminal system. Criminal Justice Policy Program at Harvard Law School. |

| 6. | Bishop et al. (2020), see note 5. |

| 7. | Budd, K. M., & Monazzam, N. (2023). Increasing public saftey by restoring voting rights. The Sentencing Project.; Aviram, H., Bragg, A., & Lewis, C. (2017). Felon disenfranchisement. Annual Review of Law and Social Science, 13, 295-311. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-lawsocsci-110316-113558 |

| 8. | Uggen, C., & Manza, J. (2004). Voting and subsequent crime and arrest: Evidence from a community sample. Columbia Human Rights Law Review, 36(1), 193-216. |

| 9. | Budd & Monazzam (2023), see note 7. |

| 10. | Porter, N., & McLeod, M. (2023). Expanding the vote: State felony disenfranchisement reform, 1997-2023. The Sentencing Project. |

| 11. | Massachusetts prisoners political action committee floundering. (2000, October). Prison Legal News. |

| 12. | Drysdale, S. (2023, April 28). Bill that would restore prison voting rights in Mass. advances out of election laws committee. State House News Service. |