System Reforms to Reduce Youth Incarceration: Why We Must Explore Every Option Before Removing Any Young Person from Home

New report highlights reforms that states and local youth justice systems can and should adopt to combat the overuse of incarceration and maximize the success of youth who are placed in alternative-to-incarceration programs.

Related to: Youth Justice, Incarceration

Executive Summary

Well designed alternative-to-incarceration programs, such as those highlighted in Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration: What Works With Youth Who Pose Serious Risks to Public Safety,1 are critically important for reducing overreliance on incarceration. But support for good programs is not the only or even the most important ingredient for minimizing youth incarceration.

To reduce overreliance on youth incarceration, alternative-to-incarceration programs must be supported by youth justice systems that heed adolescent development research, make timely and evidence-informed decisions about how delinquency cases are handled, and institutionalize youth only as a last resort when they pose an immediate threat to public safety. In addition, systems must make concerted, determined efforts to reduce the longstanding biases which have perpetuated the American youth justice system’s glaring racial and ethnic disparities in confinement.

This report will highlight state and local laws, policies and practices that have maximized the effective use of alternative-to-incarceration programs and minimized the unnecessary incarceration of youth who can be safely supervised and supported at home.

Why Does Youth Incarceration Fail, and What are the Alternatives?

Compelling research finds that incarceration is not necessary or effective in the vast majority of delinquency cases. Rather, as The Sentencing Project documented in Why Youth Incarceration Fails: An Updated Review of the Evidence,2 removing young people from their homes, schools, and communities, and placing them in institutions, is most often counterproductive. It increases the likelihood that youth will return to the justice system3 and reduces young people’s future success and wellbeing.4 Incarceration also exposes many youth to abuse.5 It contradicts clear lessons from adolescent development research by interfering with the natural process of maturation that helps most youth desist from delinquency,5 and it exacerbates trauma that many court-involved youth have suffered earlier in life.5 All of these harms of incarceration are inflicted disproportionately on youth of color. Several alternative-to-incarceration program models have proven far more effective than incarceration in steering youth who pose a significant risk to public safety away from delinquency.8

System Reforms to Minimize Youth Incarceration

This report describes reforms that states and local justice systems can and should adopt to combat the overuse of incarceration and maximize the success of youth who are placed in alternative-to-incarceration programs. Most state and local youth justice systems continue to employ problematic policies and practices that often lead to incarceration of youth who pose minimal or modest risk to public safety. The report outlines an agenda of promising and proven reforms, citing examples from across the nation where reforms are being employed constructively.

State Reforms. State policies and budgets are centrally important in any effort to minimize youth incarceration. Following are proven strategies some states are employing to reduce overuse of incarceration.

- Prohibit incarceration in state-funded youth correctional facilities for some offenses. California, Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kentucky, Maryland, Mississippi, South Dakota, Texas, and Utah have all enacted laws in recent years limiting eligibility for incarceration in state facilities.

- Create fiscal incentives that discourage local courts from committing youth to state custody, such as those enacted by California, Illinois, Ohio, and Wisconsin.

- Redirect savings from decarceration to fund alternative-to-incarceration programs. Connecticut increased its annual budget for evidence-based non-residential intervention programs from $300,000 in 2000 to $39 million in 2009. Georgia, Mississippi, Ohio, and Washington State also invest substantial sums in local alternative programs.

- Ensure access to rigorous treatment to prevent incarceration of youth with mental illnesses, following the examples set in Ohio and Texas.

- Shorten the duration of confinement for those who are incarcerated, emulating reform laws in Georgia, Kentucky, and West Virginia.

Local Reforms. Too often, local youth justice systems employ practices that ignore the lessons of adolescent development research and conflict with the evidence of what works to steer youth away from delinquency. As a result, systems can propel even youth without any history of serious offending down a path toward incarceration.9 Therefore, in addition to developing high-quality alternative to incarceration programs, local youth justice systems should replicate promising reforms underway in several parts of the country to:

- Narrow the pipeline to incarceration in the early stages of the justice system process: avoiding arrests for less serious behavior; diverting from court a substantial majority of referred cases; and minimizing the use of pre-trial detention. Heeding the research showing that these stages play a crucial role in fueling overreliance on incarceration and exacerbating disparities, many jurisdictions nationwide are pursuing reforms in these critical early stages.

- Transform probation practices to focus on connecting youth with opportunities and positive influences that support their long-term success, rather than trying to coerce behavior change by monitoring compliance with probation rules in the short term. New York City, Pierce County (Tacoma), WA, and several Ohio counties are among the jurisdictions that are vigorously pursuing probation practice reforms.

- Stop incarcerating youth for violating probation rules and conditions. Among jurisdictions that have sharply reduced confinement for violations are Santa Cruz County, CA, St. Louis, MO, and Lucas County (Toledo), OH.

- Undertake comprehensive race-conscious system reform aimed at reducing correctional placements. The twelve jurisdictions that employed this approach in a recent demonstration project reduced correctional placements by far more than the national average; and rates fell as much or more for Black youth than for the total youth population.

- Convene a stakeholder meeting to explore every alternative to incarceration before placing any young person into a longterm facility, as is done in Lucas, County (Toledo), OH, Pierce County (Tacoma), WA. Santa Cruz County, CA, and Summit County (Akron), OH.

The policies and practices described in this report are critically important, as are the intervention programs described in our Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration report. In the end, however, the most essential ingredient for reducing overreliance on youth incarceration is a mindset—a determination to seize every opportunity to keep young people safely at home with their parents and families, in their schools and communities.

Introduction

Decades of research clearly demonstrate that incarceration is not necessary or effective in the vast majority of cases of adolescent lawbreaking. Rather, as The Sentencing Project documented in, Why Youth Incarceration Fails: An Updated Review of the Evidence,10 removing youth from their homes most often harms public safety by increasing the likelihood that youth will commit new offenses and return to the justice system. Moreover, incarceration worsens young people’s likelihood of success in education and employment, and it exposes many youth to abuse. These harms of incarceration are inflicted disproportionately on youth of color, particularly Black youth.

Despite a large drop over the past two decades,11 the number of youth in correctional custody remains far too large. Fewer than one-third of youth in correctional custody on a typical day are incarcerated for serious violent offenses.12 Significant opportunities remain for state and local youth justice systems to further reduce reliance on incarceration in ways that protect the public and enhance young people’s well-being. Pursuing these opportunities – ending the wasteful, unnecessary, counterproductive, racially unjust, and often abusive confinement of adolescents – should be a top priority of youth justice reform nationwide.

The Sentencing Project’s Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration, the first of two follow up reports to Why Youth Incarceration Fails, describes promising programs that can be used to safely supervise youth who commit serious offenses and pose a significant risk of reoffending and endangering public safety. Specifically, the report identifies six model alternative-to-incarceration intervention models – all with powerful evidence of effectiveness as well as strong support for replication – that can be employed instead of incarceration for youth who pose high risk to public safety. Effective Alternatives also details the essential characteristics required for any alternative-to-incarceration program—including homegrown programs developed by local justice system leaders and community partners—to reduce young people’s likelihood of reoffending and steer them to success.

This report focuses on state and local justice system reforms that are necessary to minimize the use of incarceration for youth who do not pose a serious or immediate threat to public safety. These system reforms are crucial because, while effective alternative-to-incarceration programs are essential for youth justice systems to reduce overreliance on incarceration, they are not sufficient.

Rather, to reduce youth incarceration, effective programs must be supported by youth justice systems that steer youth away from further involvement in the justice system as often as possible at every stage of the court process. State and local justice systems must work closely with families and community partners to explore all available options to keep young people home—placing youth into institutions only as a last resort when they pose an immediate threat to public safety. Youth justice systems must implement alternative-to-incarceration programs carefully by adhering to the essential core elements of the models and ensuring that staff are highly-motivated and well-trained. Finally, systems must make concerted, determined efforts to reduce the longstanding biases which have perpetuated the glaring racial and ethnic disparities in confinement that remain American youth justice’s most prominent and troubling characteristic.

System reforms are necessary to maximize the use of effective alternatives and prevent unnecessary incarceration of youth who can be safely supervised and supported in their homes. These reforms must be pursued both at the state level, where critically important laws, policies and budgets are crafted, and at the local level where, in most states, local courts, prosecutors and probation agencies make critical decisions about how young people’s cases are handled, what punishments, rules and restrictions are placed on them, and what if any alternative programs are offered.

Maryland: A Determined Shift Away From Youth Incarceration

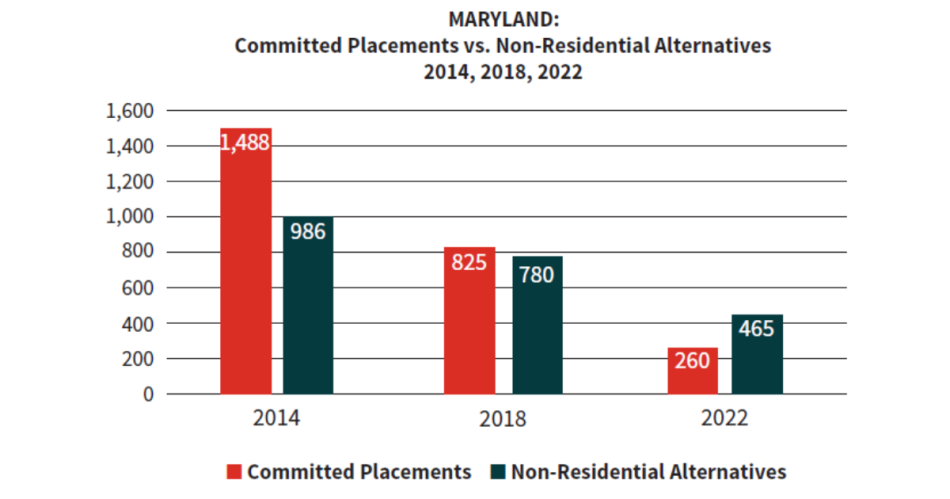

Back in 2014, Maryland sent nearly 1,500 young people to correctional placements as a consequence for delinquency. That was 50% more youth than it enrolled in evidence-based family therapy interventions that allowed young people to remain at home and continue attending school. More than 70 percent of youth sent to placements had committed only misdemeanors or other low level misdeeds such as traffic violations or status offenses – not crimes of serious violence or other felony offenses. And few youth served by home-based therapy programs – just one in five — were adjudicated for crimes of violence or other felonies.

Eight years later, Maryland sent only 260 youth to placement facilities – an 83% decline – most of them for serious offenses. Meanwhile, nearly twice as many youth (465) participated in evidence-based family therapy programs while living at home, including a substantially larger share of youth adjudicated for serious offenses — 33%, up from 20% in 2014.13

The turnabout resulted from a fundamental philosophical shift at the state’s Department of Juvenile Services (DJS). Sam Abed, who served as Maryland’ DJS Secretary from May 2011 to January 2023, noted in 2019 that “We really have drawn a line at the agency… that we don’t want kids incarcerated unless there is a public safety need to do that.”14

“For low-level offenses, we should not be using incarceration. That shouldn’t be an option,” Abed said in 2021. “What we are trying to do is not punish kids, but change their behavior. We don’t need to use a criminal justice response to change the behavior.”15

In 2022, Maryland further expanded its commitment to reducing youth incarceration when the state’s legislature enacted a new youth justice reform law. Among other provisions, the new law prohibits incarceration both for probation rule violations and for any misdemeanor offense except handgun crimes.16

State Reforms

State policies and budgets are crucial in any effort to minimize youth incarceration. In nearly every state, youth corrections facilities are overseen by the state government; however, in many states, local jurisdictions administer juvenile delinquency courts, operate some or all detention centers, or provide juvenile probation services.17 Though these funding arrangements vary, many state governments provide much of the funding required to support all of the necessary functions of the youth justice system, even when these functions are overseen by counties.

Following are strategies states can employ – and some states are already employing – to reduce overuse of incarceration.

- Enact rules to prohibit incarceration in state facilities for some offenses.

- Create fiscal incentives that discourage local courts from committing youth to state custody.

- Redirect savings from decarceration to fund alternative-to-incarceration programs.

- Ensure access to rigorous treatment to prevent incarceration of youth with mental illnesses.

- Shorten the duration of confinement for those who must be incarcerated.

1. Enact rules that prohibit incarceration in state facilities for some offenses.

Recognizing that incarceration is costly and counterproductive for youth accused of less serious offenses, several states in recent years have enacted rules prohibiting incarceration for status offenses and all or most misdemeanors. Some states have also prohibited correctional placements for non-violent felony offenses and for probation rule violations that do not involve a new offense.

For instance:

- California enacted legislation in 2007 allowing state commitments only for youth adjudicated (found guilty) for serious or violent felony offenses.18 Over the subsequent six years, the population confined in state youth correctional facilities declined 69% (from 2,115 to 659).19

- In 2006 Texas prohibited incarceration in state facilities for misdemeanor offenses, and over the next five years new commitments to state facilities fell 69% (from 2,738 to 860).20

- Florida, Georgia, Hawaii, Illinois, Kansas, Kentucky, Mississippi, South Dakota, and Utah have also prohibited state incarceration for most or all misdemeanor offenses, and in some cases lower-level felonies as well.21

- In 2022, Maryland enacted a comprehensive juvenile justice reform bill that prohibits state incarceration not only for youth who have committed misdemeanors, but also youth who have been cited for violating probation rules.22 These restrictions are pivotal given that nearly 60% of all Maryland youth committed to state custody a decade ago had a misdemeanor or probation violation as their most serious offense.23

2. Create fiscal incentives that discourage local courts from committing youth to state custody.

In many states, juvenile delinquency courts are funded and operated at the local level, and county probation offices are responsible for overseeing youth who are not committed to state custody.17 Youth correctional facilities, on the other hand, are most often funded and overseen by the states. This arrangement can create a perverse fiscal incentive that encourages courts to commit youth to state custody even though incarceration yields worse results than effective alternative-to-incarceration programs and carries a far higher overall price tag. To shift these incentives, several states have enacted new funding arrangements that encourage greater use of community alternatives, leading to dramatic reductions in confined youth populations. For example:

- In the late 1990s, California instituted a sliding scale funding formula requiring counties to pay a high share of correctional costs for youth committed to state facilities for minor offenses, and a lesser and lesser share for offenses with increasingly greater severity. This change was a key factor in helping California reduce the population in its state-run facilities from 10,000 in 1996 to 2,500 in 2007.25

- Since the 1990s, Wisconsin has incentivized community treatment of youth by providing each county with a fixed sum to support juvenile justice programs, and then charging the counties to pay the full costs of every youth placed in state correctional institutions.26 As of 2023, these funds total over $100 million per year.27

- Perhaps the most ambitious use of incentives in recent times has been the RECLAIM Ohio program, which allocates $32 million per year to Ohio counties to support local alternatives to state incarceration.28 Under the program, each county’s annual allocation is calculated based on its success in limiting the number of youth committed to state facilities. Under RECLAIM, the population confined in Ohio’s state-operated youth corrections facilities declined from over 2,500 in 1992, when RECLAIM began, to just over 300 in 2021.29

- Beginning in 2005, Illinois launched a fiscal incentive program, called Redeploy Illinois, based on Ohio’s model. The Illinois program had far more modest funding initially – less than $3 million per year through the 2013 fiscal year.30 Yet participating counties reduced commitments in the 28 participating counties by 51% from 2005 to 2010.31 By December 2021, Redeploy Illinois was operational in 45 of the state’s 102 counties, with a budget of more than $10 million, and had served nearly 5,000 youth since 2005.32

3. Redirect savings gained from decarceration to fund alternative-to-incarceration programs.

Many of the states that have prohibited incarceration for some offense categories or created fiscal incentives to discourage incarceration have devoted some or all of the funds saved from reduced correctional populations to support community-based alternative-to-incarceration programs.

- Of all the states, Connecticut has made perhaps the greatest investment in alternative to incarceration programming. After a series of scandals in its overcrowded correctional facilities in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Connecticut invested heavily in evidence-based alternative programs for court-involved youth – increasing its annual budget for evidence-based non-residential intervention programs from $300,000 in the year 2000 to $39 million by 2009.33 In 2019, the latest year for which data are available, Connecticut had the third lowest rate in the nation of youth in correctional custody.34

- Ohio, in addition to the original RECLAIM program described above, has created a Targeted RECLAIM program that provides $6 million per year to support evidence-based alternative-to-incarceration programs specifically for youth who would otherwise be placed in correctional facilities.35 Evaluations show that Targeted RECLAIM participants are far more successful than comparable peers who are placed in state youth correctional facilities.36

- In 2013, as part of a juvenile justice reform package that prohibited commitments for misdemeanor offenses, Georgia created an incentive grant that counties can use to place system-involved youth into any of 10 evidence-based programs to reduce delinquency.37 The grants, funded with more than $8 million in Fiscal Year 2021,38 served 5,640 young people in the first five years.39 Compared to the 2012 pre-reform baseline – delinquency courts in participating counties incarcerated fewer than half as many youth in each of the grant program’s first five years.40

- Mississippi included substantial new funding for alternative-to-incarceration programs as part of juvenile justice reform laws enacted in 2005 and 2006, and the state now requires every county statewide to offer community-based alternatives to incarceration.41

- Washington State provided more than $10 million to county youth justice systems in 2023 to support evidence-based and promising programs aimed at reducing delinquency.42 Programs approved for these funds include Functional Family Therapy, Multisystemic Therapy, a cognitive behavioral therapy curriculum and a program to boost success in education and employment, all of them provided in the community and geared toward youth at high or moderate risk to reoffend.43

However, it is important for states to ensure that counties use state funds to support effective alternatives to incarceration rather than expanding funding for local incarceration facilities and correctional programs. After prohibiting incarceration in state facilities for misdemeanor offenses, both California and Texas established large new funding streams to support counties’ work with delinquent youth. In 2007, California created a new Youth Offender Block Grant which provided more than $1 billion in the first decade to help counties oversee youth who could no longer be sent to state custody.44 Likewise, Texas has created several well-funded grant programs to support county youth justice systems.45 However, in both of these states the bulk of these funds have been allocated to residential confinement facilities or to funding additional probation staff, rather than to effective alternative-to-incarceration programs rooted in the community.46 States should also provide training and technical assistance to help local youth justice systems implement alternative-to-incarceration programs effectively.

4. Ensure access to rigorous treatment to prevent incarceration of youth with mental illnesses.

Roughly 70% of young people in the youth justice system suffer from one or more mental illnesses, with the most common being conduct disorder, substance abuse, depression, anxiety, or ADHD. Most youth have multiple disorders, and an estimated 20% suffer with more serious conditions such as post-traumatic stress disorder and bipolar disorder that require immediate treatment.47 Yet effective community-based treatment for these conditions is scarce throughout most of the nation, and the youth justice system has in many jurisdictions become a default provider of mental health services for youth with mental illnesses.48 Josh Weber, who directs the Council of State Governments Justice Center’s juvenile justice program, calls the absence of behavioral health programming as “a big gap” – describing it as perhaps the single biggest reason for unnecessary youth incarceration nationwide.49

Some states have taken effective action to address the need for community-based mental health care to help youth with mental health issues avoid behavior problems and remain at home:

- Ohio’s Behavioral Health/Juvenile Justice (BH/JJ) Initiative provides intensive evidence-based mental health treatment for court-involved youth with mental health diagnoses who score as high risk to reoffend. Operated as a partnership between the state’s juvenile corrections and mental health agencies, the program has provided Functional Family Therapy, Multisystemic Therapy, or other evidence-based mental health interventions to more than 5,000 youth since 2006.50 The most recent evaluation showed that participating youth saw significant improvements in mental health and a large drop (roughly half) in both delinquency charges and suspension/expulsion from school after enrolling in BH/JJ programs.51

- Texas has long funded two programs for court-involved youth with mental health issues in the earlier stages of the court process. The Front-End Diversion Initiative assigns youth with mental illnesses who are accused of delinquent offenses but not yet adjudicated to probation officers who are specially trained on mental health issues. A 2012 evaluation showed that participants received far more mental health care and were connected far more often to community resources than comparable youth placed on standard probation, and the program sharply reduced recidivism.52 Texas’ Special Needs Diversionary Program provides a similar intervention for youth who have already been adjudicated delinquent. Two evaluation studies have found that this program also reduced recidivism.53

5. Shorten the duration of confinement for those who must be incarcerated.

Once youth are incarcerated, keeping them away from home for a longer period than necessary is wasteful and counterproductive. Research has clearly demonstrated that longer periods of incarceration (lasting more than six months) do not improve recidivism outcomes,54 with mixed findings even for high-risk youth.55 In fact, many studies find that longer periods of incarceration increase recidivism.56 Yet in many states youth are incarcerated for an average of well over one year.57

Some states in recent years have taken steps to reduce lengths of stay for youth placed in correctional facilities or other institutions:

- In Virginia, after data analysis revealed that longer periods of incarceration were associated with higher recidivism, the state’s Board of Justice approved new guidelines in 2015 reducing the duration of incarceration for youth committed to state correctional facilities. Within three years, the average length of stay fell from 14 months to 8 months.58

- In Kentucky and West Virginia comprehensive new juvenile justice laws passed in 2014 and 2015, respectively, included limitations on lengths-of-stay for youth in correctional placements.59

New York City: Reducing Incarceration Through Strong Alternatives And Better Decision-Making

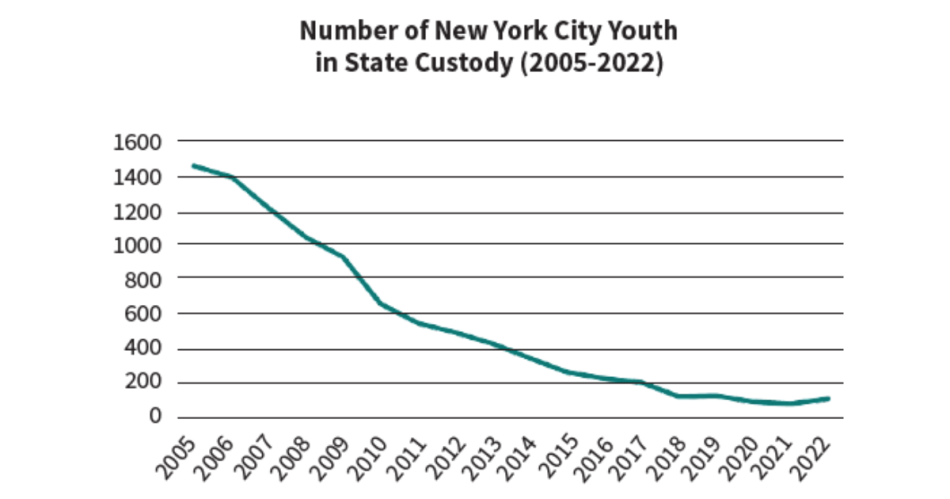

In the early years of this century, well over 1,000 New York City young people were confined in state-funded institutions every night as a consequence for delinquency,60 the vast majority of them Black or Latinx.61 Most of the facilities were located upstate and staffed mostly by white correctional officers who had little in common with the incarcerated young people.62

Outcomes were terrible: 70% of boys released from state facilities were re-arrested within two years;63 by age 28, 89% of boys were re-arrested and 71% were re-incarcerated as adults.64 A 2009 federal justice department investigation found that the facilities were violent and abusive: excessive use of force by staff caused “an alarming number of serious injuries to youth, including concussions, broken or knocked-out teeth, and spiral fractures.”65

Today, New York City doesn’t place any youth in state-funded youth correctional facilities. In 2022, it sent fewer than 100 youth into any type of residential placement, and these youth are now housed in small, therapeutically oriented facilities within the City.66

The City’s remarkable reduction in youth incarceration stems from a series of reform steps.

- In 2003, the City introduced an objective screening process to reduce the use of pre-trial detention, launched a variety of alternative-to-incarceration programs and announced a goal to reduce state commitments to zero.67

- Those reforms and revelations of abuse within state facilities68 were key factors behind a 55% drop in commitments from city courts between 2003 and 2011.69

- In 2009, a state task force recommended: using correctional placements only for youth who posed high risk for reoffense; and expanding the use of community-based alternatives to placement.70

- Since 2010, the NYC Department of Probation has accelerated the pace of reform by introducing a structured decision-making grid to minimize unnecessary correctional placements; increasing the share of youth diverted from formal court processing; decreasing the use of detention in response to probation rule violations; and further expanding the use of community-based alternative-to-incarceration programs.71

- In 2012, New York’s state legislature approved the “Close to Home Initiative,” which allowed New York City to stop sending youth to state correctional facilities. Instead, the City created its own network of small, privately operated, therapeutically-oriented facilities.72

“By developing strong alternative programs and improving decision making at every stage of the process, NY City has shown what it takes to drastically reduce incarceration,” said Bermudez, “and to do it safely.”73

Local Reforms

How local system players manage the cases of youth referred for prosecution or placed on probation, and the mindset they bring to their work, are pivotal in reducing the unnecessary use of incarceration. Too often, youth justice systems employ practices that ignore the lessons of adolescent development research and conflict with the evidence of what works to steer youth away from delinquency. As a result, systems can propel youth – even those without a history of serious offending – down a path toward incarceration.

To correct these problematic practices and minimize overreliance on incarceration, local youth justice systems can emulate innovative jurisdictions that are taking steps to:

- Narrow the pipeline to incarceration by reducing arrests, expanding diversion (in lieu of formal court processing), and reducing use of pretrial detention.

- Transform probation practices to align with adolescent development research and focus on youth success.

- Stop incarcerating youth for violating probation rules and conditions.

- Undertake comprehensive race-conscious system reform aimed at reducing correctional placements.

- Explore every option before removing any young person from home.

1. Narrow the pipeline to incarceration.

Young people’s likelihood of being incarcerated is heavily dependent on decisions made in the early stages of the justice system. Whenever young people are arrested (versus given a warning by police or a civil citation), whenever they are referred on delinquency charges and have their cases formally processed in juvenile court (instead of diverted), and whenever young people are locked in detention pending their court hearings (instead of being allowed to remain at home), their odds of continued involvement in the justice system – and subsequent incarceration – increase substantially.74

Overuse of arrests, formal court processing, and detention play a critical role in perpetuating racial and ethnic disparities in incarceration. These early stages of the process have the greatest disparities in the youth justice system, and studies consistently find that these disparities are driven at least partly by biased decision-making.

Therefore, among the most important steps local justice systems can take to reduce overreliance on incarceration – and many systems are taking – include reforms to:

- Avoid arrests for less serious misbehavior at school and in the community: Many studies show that youth who get arrested during adolescence have substantially more involvement in the justice system – and substantially higher dropout rates – than comparable youth who engage in similar misbehaviors but don’t get arrested.75 Local jurisdictions have taken a variety of steps to reduce arrests.

- In the wake of national protests after George Floyd’s murder, nearly 50 jurisdictions removed law enforcement officers from their schools.76 Unfortunately, some jurisdictions have reversed course since 2020 and returned law enforcement officers to schools;77 however, there remains no evidence that stationing officers in schools improves public safety, and considerable evidence that it harms student wellbeing.78

- Jurisdictions such as Clayton County, GA, and Philadelphia, PA, have drastically reduced arrests at school after crafting new rules that prohibit arrests at school for a variety of less serious offenses.79

- Still other jurisdictions – like Baltimore City, MD – have vastly reduced school arrests after embracing a restorative justice approach to school discipling.80

- For misbehavior outside of school, police officers can be empowered to refer youth to pre-arrest diversion programs in lieu of arrest, or to issue civil citations. For instance, Florida police issued civil citations (instead of making arrests) to more than 11,000 youth in 2022,81 and research shows these youth are far less likely to re-enter the justice system than comparable peers who get arrested for the same offenses.82

- Divert from court a substantial majority of referred cases and allow community organizations, rather than courts or probation, to address misbehavior outside the justice system. Powerful new research makes abundantly clear that formally processing youth in juvenile court – criminalizing adolescent misbehavior – results in far worse outcomes: far higher subsequent involvement in the justice system, and worse educational and career success.83 For the large majority of delinquency cases – other than youth involved in serious offending – diversion from the justice system yields better outcomes both for public safety and youth success.84 Davidson County (Nashville), TN more than tripled the share of new cases diverted from 2013 to 2020 (from 17% to 54%) and empowered a network of community-based youth development organizations to oversee their cases.85

- Minimize the use of locked detention for youth pending their court hearings. Research finds that detention in the pre-trial period substantially increases the likelihood that youth will be placed in a residential facility if found delinquent by a judge; and even short stays in detention reduce educational attainment and increase the likelihood of subsequent involvement in the justice system.86 Through its Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative (JDAI), the Annie E. Casey Foundation has created a comprehensive and effective model for combatting overreliance on detention based on eight core principles.87 More than 300 jurisdictions nationwide – home to nearly one-third of all US children – adopted the JDAI model, and participating sites reduced average daily detention populations in detention by 50%, with no harm to public safety.88 An independent evaluation found that jurisdictions participating in JDAI reduced their detention populations five times more than other jurisdictions within their states.89 Tellingly, participating JDAI sites reduced their commitments to state custody by 63% — even more than they reduced detention admissions.90

- Research finds that youth of color are often treated more harshly than white youth at these critical early stages, and disparities tend to be especially large.91 Therefore, local justice systems should collect and carefully analyze data by race and ethnicity at these early stages, and they should use the data to identify problematic practices that exacerbate disparities and institute reforms that ensure greater equity.

2. Transform probation practices to align with adolescent development research and focus on youth success.

Probation is by far the most common outcome in cases referred to juvenile delinquency courts nationwide. Two-thirds of youth adjudicated delinquent in 2020 (analogous to being found guilty in criminal court; 89,000 youth) were ordered to probation, and nearly as many more were placed on informal probation either as part of a deferred prosecution agreement or consent decree (an additional 44,000 youth) or after their case was diverted from formal court processing (an additional 32,000 youth).92 Yet voluminous research shows that the traditional approach to juvenile probation, in which courts hand youth a long list of standard rules and conditions and then a probation officer monitors their compliance, has little or no effect on future offending.93 Many of the most common practices in probation conflict with research and expert opinion on effective interventions to stem delinquent conduct.94

For instance, imposing long lists of standard conditions and focusing probation on compliance conflicts with the lessons of adolescent behavior and brain development research.95 Attempting to coerce behavior change through threats of punishment rather than incentives for positive behavior ignores the evidence showing that teens are unlikely to be swayed by threats of future punishment, but highly responsive to positive incentives.96 Also, probation agencies too often make critical decisions about young people’s cases without involving their parents and families.97 Research shows that parents continue to play a pivotal role in their children’s lives, and many of the most effective intervention models for combatting delinquency focus on families.98 Yet most probation agencies still struggle with, or do not prioritize, family engagement to ensure that families are integrally involved in crafting their children’s case plans and making key decisions.99

Since 2018, several leading organizations in the youth justice field—including the Annie E. Casey Foundation, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges, and the National Center for Juvenile Justice—have called on juvenile courts and probation agencies to reorient probation away from the traditional surveillance-compliance mindset.100 Specifically, the new best-practice guidance urges youth justice system leaders to:

- Stop ordering all youth on probation to comply with a standard list of probation rules and conditions.101

- Shift probation’s focus away from compliance monitoring and toward case planning, brokering helpful services and opportunities in the community, and support for young people’s success.102

- Adopt a family-engaged case planning process in which probation officers partner with youth and families to identify goals and activities that will help the young person avoid problem behaviors and achieve long-term success.103

- Encourage positive behavior change through incentives and rewards for youth to meet behavior expectations and achieve their case plan goals.104

- Connect young people with activities in the community where youth can develop new skills and build relationships with caring adults and positive peers.105

- Carefully monitor data measuring probation’s impact on youth by race, ethnicity and gender, and make reducing disparities a clear and explicit goal for probation.106

A number of local justice systems around the country are adopting these principles. In 2011 and 2012, New York City’s Department of Probation pioneered the development of the family-engaged case planning model which has subsequently been documented in a practice guide available to jurisdictions nationwide.107 Pierce County (Tacoma), WA has created an Opportunity-Based Probation model that offers an array of rewards and incentives for youth on probation to achieve the goals of their case plans.108 Pierce County has also created a network of local community-based organizations that provide positive youth development opportunities for youth on probation.109 Ohio’s Department of Juvenile Justice has made probation transformation a statewide goal, organized in-depth regional training sessions on probation transformation, and made advancing key elements of probation transformation a requirement for counties in their applications for state juvenile justice funding.110

3. Stop incarcerating youth solely for violating probation rules and conditions.

While the case for transforming probation is compelling, even jurisdictions that do not embrace this new paradigm can and should stop incarcerating youth solely for rule-breaking behaviors and non-compliance with probation orders that do not involve new crimes. Research makes clear that this practice is counterproductive for both public safety and youth success, and that it exacerbates racial and ethnic disparities in incarceration.111 Yet, as the Center for Children’s Law and Policy has explained, “In many jurisdictions, technical violations represent one of the leading reasons for admission to detention or out-of-home placement.”112 In South Carolina, for instance, the top four offenses among youth committed to state custody in 2019 all involved probation violations.113 In Maricopa County (Phoenix), AZ, 48% of youth sent to state custody in Fiscal Year 2020 were committed for probation violations.114 In Maryland, 27% of commitments to state custody in 2013 were the result of probation violations, not new offenses.115

In a 2017 resolution, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges (NCJFCJ) urged juvenile courts nationwide to “ensure that detention or incarceration is never used as a sanction” for youth who violate probation rules.116 In a new 2022 toolkit on judges’ roles in reforming juvenile probation, NCJFCJ again urged juvenile courts to stop confining youth as a consequence for rule violations, and – noting that youth of color are confined for violations disproportionately – the toolkit stated that “rejecting the use of confinement as a response to probation rule violations… represents one of the single most important and valuable steps that juvenile courts can take to reduce system disparities.”117

To reduce the use of incarceration in response to rule violations, Santa Cruz County, CA no longer places youth into correctional or residential treatment facilities as a consequence for rule violations, and it has dramatically reduced the number of youth placed in short-term detention for violations.118 St. Louis, MO and Lucas County (Toledo), OH have also sharply reduced detention in response to rule violations.119

4. Undertake comprehensive race-conscious system reform aimed at reducing correctional placements.

America’s youth justice systems continue to incarcerate youth of color, especially Black youth, at far higher rates than their white peers. In 2020, the last year for which data are available, 41% of youth newly incarcerated nationwide were Black, even though Black youth make up 15% of the total youth population.120

From 2012 through 2020, 12 jurisdictions participated in the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s “Deep End Initiative” to reduce out-of-home placements following adjudication, especially for youth of color.121 As part of the initiative, the sites reviewed all decision points where youth may enter the justice system or penetrate deeper to more serious levels of supervision (arrest, formal processing in court, revocation of diversion for non-compliance, filing of a probation violation, incarceration), as well as mechanisms at each decision point that allow youth to exit the justice system or at least to remain at home (no arrest, diversion from formal processing, placement on probation or another at-home disposition). Sites examined how each stage affected Black youth and other youth of color differently than white youth, and they strategized to address the disparities they uncovered and to reduce the share of youth – especially youth of color – who were propelled at each stage to deeper involvement in the justice system.122

The Casey Foundation reported that participating sites reduced the number of new correctional placements by far more than the national average. By 2017, sites that started in 2012 had reduced their correctional placements by 54% (versus a national decline of 25%), and sites that started in 2014 reduced correctional placements by 37% (versus a national decline of 8%). Just as encouraging, correctional placements for the sites fell as much or more for African American youth as for the total youth population. Also, in all nine Deep End sites that provided complete data, the decline in placements for African American youth far outpaced the national average.123

While the Casey Foundation’s Deep End Initiative is no longer operating, the tools and techniques employed to achieve these favorable results can be applied by any jurisdiction, at any time. A “Deep End Toolkit” is still available on the Annie E. Casey Foundation’s website.124

5. Explore every option before removing any young person from home.

The final step local youth justice systems can take to minimize incarceration comes when a young person commits serious offenses or reoffends repeatedly, and therefore becomes a candidate for placement in a correctional facility or other residential program. Rather than routinely endorsing decisions to remove any young person from home in these circumstances, the National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges recommended in 2022 that juvenile courts and probation agencies: “Make it a practice to convene a family-team meeting and/or case staffing for any young person being considered for residential placement, and use these review sessions to explore every available option or alternative to placement.”125

Among the jurisdictions that have instituted this practice are Santa Cruz County, CA, Lucas County (Toledo) and Summit County (Akron), Ohio, and Pierce County, WA.126 Typically, the meetings include system staff, mental health experts, and representatives from child-serving organizations in the community – and often the young person, his or her family, and other important figures in the child’s life. The NCJFCJ toolkit urged that: “All parties participating in these meetings should generate ideas together seeking to answer the question: what will it take to keep this young person at home under probation safely?”125

Santa Cruz: Child and Family Team Meetings Doing What It Takes To Keep Young People Home Safely

In the nearly 25 years since it became a model site for the Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, Santa Cruz County has drastically reduced its reliance not only on pre-trial detention, but also on incarceration for youth found delinquent in court. Indeed, in recent years correctional placements have continued to plummet: Santa Cruz County sent 26 youth to placement in 2015 but only five in 2022 – a drop of 81%.128

Among Santa Cruz County’s most important strategies to minimize placements is the “Child and Family Team” meeting, where “professionals from various county agencies and community-based organizations . . . come together to meet with the family and strategize how to best meet the needs of the youth and family.”129

Some CFT meetings are convened early in a young person’s case, to help identify caring adults in the young person’s life who might provide support and to craft a probation plan that best meets the needs of the young person and family. In other cases, the meetings are called to seek alternatives to placement for youth who have just been adjudicated for a serious offense, or for youth on probation or in home-based wraparound care who continue to break rules or engage in unsafe behaviors.

Recently, deputy probation officer Gina Castaneda described the case of a boy, then 15, who was arrested in 2021 for possession of a loaded firearm. The boy was suspected of gang involvement, had serious problems with school attendance and achievement, and got little supervision from his parents who had demanding work schedules, Castaneda said.130

At the CFT meeting, probation staff introduced the family to community-based service providers and worked with the family to devise a supervision plan that would allow the boy to remain at home. Under the plan, the boy re-enrolled in school, participated in electronic monitoring, and agreed to remain at home, except for school, counseling and other approved activities. To enhance supervision at home, the boy’s grandmother got more involved in his life, while the probation department connected the father with parenting skills training. The probation department also encouraged the father to set aside at least 10 minutes every day for father-son conversations and provided gift cards to pay for family outings.131

In addition, the probation department enrolled the boy in a community-based youth center, the Azteca clubhouse, and a counseling program. Probation personnel also phoned the boy every day and transported him to and from one activity or another every day after school.132

Not everything went smoothly in the boy’s case, Castaneda reports. He received several probation violations due to uneven school attendance or poor grades, missing scheduled counseling appointments, and more. Things started to improve, Castaneda recalls, when probation referred him to the County’s evening reporting center program, which suited him better than the Azteca clubhouse.133

Despite his ups and downs, the boy has never again been placed in custody. He remains in school, and he has matured significantly, Castaneda says, in part because he recently became a father and takes an active part in his child’s life.134

“We met the family where they are at and listened to what they needed. We worked with them, and the youth, and connected them to our community partners,” says Jose Flores, Director of the Santa Cruz County Probation Department’s Juvenile Division. “We have been able to help him stay out of serious trouble. That’s our goal.”

Conclusion

The leaders of youth justice systems nationwide as well as the legislators who enact laws and approve budgets for youth justice must heed the compelling evidence showing that incarceration is a failed strategy for reversing delinquent behavior – and that it is imposed disproportionately on youth of color. They must recognize that incarceration should be imposed only on young people who present a serious and immediate threat to other people’s safety, and they must fund and deliver effective alternative-to-incarceration programs to keep many youth at home safely who are currently being incarcerated.

In the end, the most essential ingredient for reducing overreliance on youth incarceration is a determination to explore every option to keep young people at home safely, providing youth with the support and assistance they require to avoid further offending, participate in the normal rites of adolescence, and mature toward a healthy adulthood.

| 1. | Mendel, R. (2023). Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration: What Works With Youth Who Pose Serious Risks to Public Safety. The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Mendel, R. (2023). Why youth incarceration fails. The Sentencing Project. |

| 3. | Why Youth Incarceration Fails. See note 2. |

| 4. | Why Youth Incarceration Fails. See note 2 |

| 5. | Why Youth Incarceration Fails. See note 2. |

| 6. | Why Youth Incarceration Fails. See note 2. |

| 7. | Why Youth Incarceration Fails. See note 2. |

| 8. | Effective Alternatives to Youth Incarceration. See note 1. |

| 9. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A hidden key to to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project. |

| 10. | Why youth incarceration fails. See note 2. |

| 11. | Rovner, J. (2023). Youth justice by the numbers. The Sentencing Project. |

| 12. | Sickmund, M., Sladky, T.J., Puzzanchera, C., & Kang, W. (2022). Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement. OJJDP. |

| 13. | Maryland Department of Juvenile Services (2015). Data Resource Guide Fiscal Year 2014; Maryland Department of Juvenile Services (2018). Data Resource Guide Fiscal Year 2018; Maryland Department of Juvenile Services (2022). Data Resource Guide Fiscal Year 2022. |

| 14. | Collins, D. (2019, December 28). “Maryland moving toward better mix of treatment for juvenile offenders, experts say.” WBAL TV. |

| 15. | McFadden, R. (2021, January 2). “Juvenile Detention Declined, Yet Black Children Detained at High Rate. Capital New Service. |

| 16. | For a detailed review of provisions in the new law, Maryand Senate Bill 691, see: Annie E. Casey Foundation (2022, June 21). “Maryland Enacts Sweeping Youth Justice Reforms.” |

| 17. | Information about the structure of each state’s juvenile justice system can be found on the National Center for Juvenile Justice’s website: Juvenile Justice GPS (Geography, Policy Practice & Statistics). |

| 18. | California allowed incarceration only for a list of 30 very serious offenses, including murder, rape, robbery, kidnapping, and voluntary manslaughter. A complete list of these 707(b) offenses can be seen on the website of the California state legislature. |

| 19. | Tafoya, S., & Hayes, J. (2014). Just the facts: Juvenile justice in California. Public Policy Institute of California. |

| 20. | Legislative Budget Board. (2013). Characteristics of juveniles in Texas juvenile justice department state correctional facilities before and after the 2007 reforms. |

| 21. | Pew Charitable Trusts. (2015). Re-Examining juvenile incarceration: High cost, poor outcomes spark shift to alternatives.; Pew Charitable Trusts. (2019). Utah’s 2017 juvenile justice reform shows early promise: Law aims to improve public safety outcomes across the state.; Durnan, J., Olsen, R., & Harvell, S. (2018). State-led juvenile justice systems improvement implementation progress and early outcomes. Urban Institute.; National Juvenile Justice Network & Texas Public Policy Foundation. (2013). The comeback states: Reducing youth incarceration in the United States; Illinois Department of Human Services. (2022). Redeploy Illinois annual report calendar and fiscal years 2015-2021. |

| 22. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2022). Maryland enacts sweeping youth justice reforms. |

| 23. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2015). Doors to DJS Commitment: What drives juvenile confinement in Maryland? |

| 24. | Information about the structure of each state’s juvenile justice system can be found on the National Center for Juvenile Justice’s website: Juvenile Justice GPS (Geography, Policy Practice & Statistics). |

| 25. | National Juvenile Justice Network & Texas Public Policy Foundation (2013), see note 21. |

| 26. | Carmichael, C. (2015). Juvenile justice and youth aids program. Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau. |

| 27. | Wisconsin Legislative Fiscal Bureau. (2021). 2021-23 Wisconsin state budget: Comparative summary of provisions. |

| 28. | Golon, J. (2023). LBO analysis of executive budget proposal. Ohio Department of Youth Services. |

| 29. | Juvenile Justice Coalition. (2015). Bring youth home: Building on Ohio’s deincarceration leadership. |

| 30. | Annual budgets for Redeploy Illinois since 2010 are available online at the website of the Illinois Office of Management and Budget. |

| 31. | State of Illinois Department of Human Services. (2011). Redeploy Illinois annual report to the governor and the general assembly calendar years 2010 – 2011. |

| 32. | Illinois Department of Human Services. (2022). Redeploy Illinois annual report calendar and fiscal years 2015-2021.; Office of Governor JB Pritzker. (2023). Illinois state budget: Fiscal year 2024. |

| 33. | Mendel, R.A. (2013). Juvenile justice reform in Connecticut: How collaboration and commitment have improved public safety and outcomes for youth. Justice Policy Institute. |

| 34. | Sickmund, M., Sladky, T.J., Puzzanchera, C., and Kang, W. (2021). Easy access to the census of juveniles in residential placement: State comparisons. OJJDP. |

| 35. | Policy Matters Ohio. (2021). Promise over punishment. |

| 36. | Spiegel, S., Lux, J., Schweitzer, M., & Latessa, E. (2018). Keeping kids close to home: Targeted RECLAIM 2014 & 2015 outcome evaluation. University of Cincinnati Corrections Institute. |

| 37. | Carl Vinson Institute of Government Project Team. (2018). Georgia juvenile justice incentive grant program: Five year evaluation report (2013-2018). The University of Georgia. |

| 38. | Georgia Criminal Justice Coordinating Council. (2021). FY21 juvenile justice incentive grant program (JJIG) awards. |

| 39. | Carl Vinson Institute of Government Project Team (2018), see note 37. |

| 40. | Carl Vinson Institute of Government Project Team (2018), see note 37. |

| 41. | National Juvenile Justice Network & Texas Public Policy Foundation (2013), see note 21 |

| 42. | Senate Bill 5092, 67th Legislature, 2021 Regular Session (Washington State 2021). https://lawfilesext.leg.wa.gov/biennium/2021-22/Pdf/Bills/Senate%20Passed%20Legislature/5092-S.PL.pdf?q=20210428145030 |

| 43. | Washington State Department of Children, Youth & Families. (2021). Report to the Washington state legislature: Juvenile court block grant. |

| 44. | Cate, S. (2016). The politics of prison reform: Juvenile justice policy in Texas, California and Pennsylvania. Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/1639 |

| 45. | Texas Juvenile Justice Department. (2016). Community juvenile justice appropriations, riders and special diversion programs. |

| 46. | Cate (2016), see note 44. |

| 47. | Cocozza, J., & Shufelt, S. (2006). Youth with mental health disorders in the juvenile justice system: Results from a multi-state prevalence study. National Center for Mental Health and Juvenile Justice. |

| 48. | Cocozza, J., Skowyra, K., & Shufelt, S. (2010). Addressing the mental health needs of youth in contact with the Juvenile justice system in system of care Communities. Technical Assistance Partnership for Child and Family Mental Health.; Seiter, L. (2017). Mental health and juvenile justice: A review of prevalence, promising practices, and areas for improvement. The National Technical Assistance Center for the Education of Neglected or Delinquent Children and Youth.; National Association of Counties. (2014). County concerns: Behavioral health and juvenile justice. |

| 49. | Josh Weber, Deputy Division Director of the Council of State Governments Justice Center, interview with the author, February 2, 2023. |

| 50. | Butcher, F., Kretschmar, J., Yang, L., Rinderle, D., & Turnamian, M. (2020). An evaluation of Ohio’s behavioral health/juvenile justice (BHJJ) initiative. Begun Center for Violence Prevention Research and Education Jack, Joseph, and Morton Mandel School of Applied Social Sciences Case Western Reserve University. |

| 51. | Butcher et al. (2020), see note 50. |

| 52. | Colwell, B., Villarreal, S. F., & Espinosa, E. M. (2012). Preliminary outcomes of a pre-adjudication diversion initiative for juvenile justice involved youth with mental health needs in Texas. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 39(4), 447–460. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854811433571 |

| 53. | Cuellar, A., McReynolds, L., Wasserman, GA. (2006). A cure for crime: can mental health treatment diversion reduce crime among youth? J. Pol. Anal. Manage., 25(1), 197-214. https://doi.org/10.1002/pam.20162; Jeong, S., Lee, B. H., & Martin, J. H. (2014). Evaluating the effectiveness of a special needs diversionary program in reducing reoffending among mentally ill youthful offenders. International Journal of Offender Therapy and Comparative Criminology, 58(9), 1058–1080. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306624X13492403 |

| 54. | Feierman, J., Mordecai, K., & Schwartz, R. (2015). Ten strategies to reduce juvenile length of stay. Juvenile Law Center. |

| 55. | Winokur, K. P., Smith, A., Bontrager, S. R., & Blankenship, J. L. (2008). Juvenile recidivism and length of stay. Journal of Criminal Justice, 36(2), 126-137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2008.02.001; Lovins, B. (2013). Putting wayward kids behind bars: The impact of length of stay in a custodial setting on recidivism. University of Cincinnati. |

| 56. | Why youth incarceration fails. See note 2. |

| 57. | González, T. (2017). Youth incarceration, health, and length of stay. Fordham Urban Law Journal, 45(1), 2. https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/ulj/vol45/iss1/2 |

| 58. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2019). Data tells how Virginia’s youth justice system is headed toward a better future. |

| 59. | Pew Charitable Trusts. (2014). Kentucky’s 2014 juvenile justice reform.; Pew Charitable Trusts. (2016). West Virginia’s 2015 juvenile justice reform. |

| 60. | Data provided by Sara Workman, Executive Director, Justice Analytics and Child Welfare Reporting, Division of Policy, Planning and Measurement, N.Y. City Administration for Children’s Services, August 29, 2023. |

| 61. | Weissman, W.; Ananthakrishnan, V.; & Schiraldi, V, (2019). Moving Beyond Youth Prisons, Columbia Justice Lab. |

| 62. | Weissman et al. (2019), see note 109 |

| 63. | N.Y. State Office of Children and Family Services (2011). OCFS Fact Sheet: Recidivism Among Juvenile Delinquents and Offenders Released from Residential Care in 2008. |

| 64. | Colman, R., Kim, D.H., Mitchell-Herzfeld, S., & Shady, T.A. (2008). Long-Term Consequences of Delinquency: Child Maltreatment and Crime in Early Adulthood. N.Y. State Office of Children and Family Services. |

| 65. | King, L., Acting U.S. Assistant Attorney General (2009, August 14). Letter to The Honorable David A. Paterson, Governor of New York. Investigation of the Lansing Residential Center, Louis Gossett, Jr. Residential Center, Tryon Residential Center, and Tryon Girls Center. |

| 66. | NY City data show that 89 youth were placed into Close to Home facilities in the 2022 calendar year: 66 youth in non-secure placement facilities and 23 in limited secure placements facilities. Data downloaded from New York City Flash Report Indicators, https://data.cityofnewyork.us/City-Government/Monthly-Flash-Report-indicators/2ubh-v9er. |

| 67. | Ferone, J.J., Salsich, A., & Fratello, J. (2014). The Close to Home Initiative and Related Reforms in Juvenile Justice. Vera Institute. |

| 68. | Lewis, M. (2006). Custody and Control: Conditions of Confinement in New York’s Juvenile Prisons for Girls. Human Rights Watch; and Feldman, C. (2007, March 4). “State Facilities’ Use of Force Is Scrutinized After a Death.” New York Times. |

| 69. | Moving Beyond Youth Prisons, see note 109; and Ferone et al (2014), see note 115. |

| 70. | Task Force on Transforming Juvenile Justice (2009). Charting a New Course: A Blueprint for Transforming Juvenile Justice in New York State. |

| 71. | Ferone et al (2014), see note 115; and Moving Beyond Youth Prisons, see note 109. |

| 72. | Moving Beyond Youth Prisons, see note 109. |

| 73. | Ana Bermudez, former Commissioner, N.Y. City Department of Probation, email correspondence with the author, September 1, 2023. |

| 74. | Why youth incarceration fails. See note 2 |

| 75. | Diversion: A hidden key to to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. See note 9. |

| 76. | Mendel, R. (2021). Back-to-school action guide: Re-engaging students and closing the school-to-prison pipeline. The Sentencing Project. |

| 77. | Morton, N. (2022, October 11). Some districts that removed police from schools have brought them back. The Hechinger Report. https://hechingerreport.org/student-protests-prompted-schools-to-remove-police-now-some-districts-are-bringing-them-back/ |

| 78. | Mendel (2021), see note 76. |

| 79. | Mendel (2021), see note 76. |

| 80. | Skiba, R.J., & Losen, D.J. (2015). From reaction to prevention turning the page on school discipline. American Educator. |

| 81. | Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. (2023). Civil citations & other alternatives to arrest dashboard. |

| 82. | Pla, J. (2014). Civil Citation Effectiveness Review. Florida Department of Juvenile Justice. Florida Department of Juvenile Justice.; Nadel, M., Bales, W., & Pesta, G. (2019). An assessment of the effectiveness of civil citation. Florida State University. |

| 83. | Cauffman, E.E., Beardslee, J., Fine, A.D., Frick, P.J., & Steinberg, L.D. (2021). Crossroads in juvenile justice: The impact of initial processing decision on youth 5 years after first arrest. Development and Psychopathology, 33, 700 – 713. https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942000200X; Petrosino, A., Turpin-Petrosino, C., & Guckenburg, S. (2010). Formal system processing of juveniles: Effects on delinquency. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 6(1), 1-88. https://doi.org/10.4073/csr.2010.1; Wilson, H. A., & Hoge, R. D. (2013). The effect of youth diversion programs on recidivism. Criminal Justice and Behavior, 40(5), 497-518. https://doi.org/10.1177/0093854812451089 |

| 84. | Mendel (2022), see note 9. |

| 85. | Mendel (2022), see note 9. |

| 86. | Mendel (2022), see note 9. |

| 87. | The eight core strategies of JDAI are collaboration; data-driven decisionmaking; objective admissions policies; alternatives to detention; expedited case processing; reducing detention for youth held on warrants for failure to appear, awaiting placement to correctional or treatment facilities; or charged with probation violations. JDAI core strategies. Annie E. Casey Foundation. |

| 88. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2019). Latest JDAI results: Significant reductions in juvenile incarceration and crime. |

| 89. | University of California, Berkeley Law. (2012). JDAI sites and states. |

| 90. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2019), see note 88. |

| 91. | Mendel (2022), see note 9; Mendel (2022), see note 2. |

| 92. | Sickmund, M., Sladky, A., & Kang, W. (2023). Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985-2020. OJJDP. |

| 93. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2018). Transforming juvenile probation: A Vision for getting it right. |

| 94. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018), see note 93. |

| 95. | National Juvenile Defender Center. (2016). Promoting positive development: The critical need to reform youth probation orders. |

| 96. | Goldstein, N. E. S., NeMoyer, A., Gale-Bentz, E., Levick, M., & Feierman, J. (2016). “You’re on the right track!” Using graduated response systems to address immaturity of judgment and enhance youths’ capacities to successfully complete probation. Temple Law Review, 88, 805–836. https://www.courts.ca.gov/documents/BTB25-1I-02.pdf |

| 97. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018), see note 93 |

| 98. | Fagan, A. (2013). Family-focused interventions to prevent juvenile delinquency: A case where science and policy can find common ground. Criminology & Public Policy, 12, 617–650. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12029; Henggeler, S. W. (2015). Effective family-based treatments for adolescents with serious antisocial behavior. In J. Morizot & L. Kazemian (Eds.), The development of criminal and antisocial behavior: Theory, research and practical applications (pp. 461–475). Springer International Publishing AG. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-08720-7_29 |

| 99. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018), see note 93 |

| 100. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018), see note 93; National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. (2022). The role of the judge in transforming juvenile probation.; National Center for Juvenile Justice. (2019). Desktop guide to good juvenile probation practice. (This resource was updated and reformatted as an online resource in 2019. The previous version, created in 2002, recommended a far different vision of probation. |

| 101. | National Juvenile Defender Center (2016). Promoting positive development: The critical need to reform youth probation orders (Issue brief ). |

| 102. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2018), see note 93 |

| 103. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2022). Family-engaged case planning: A practice guide for transforming juvenile probation. |

| 104. | Goldstein, N. E. S., NeMoyer, A., Gale-Bentz, E., Levick, M., & Feierman, J. (2016). “You’re on the right track!” Using graduated response systems to address immaturity of judgement and enhance youths’ capacities to successfully complete probation. Temple Law Review, 88, 805–836. |

| 105. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2018), see note 93 |

| 106. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2018), see note 93 |

| 107. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2022). Family-engaged case planning: A practice guide for transforming juvenile probation. |

| 108. | SAJE Center. (2019). Opportunity-based probation: A brief report. |

| 109. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2022). Pierce county youth probation: Few youth need out-of-home placement.; Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2018). Pierce county: Trailblazer for probation transformation. |

| 110. | Ohio Department of Youth Services. (2021). Enhanced probation services.; The Ohio Department of Youth Services. (2021). Ohio Department of youth services annual report: Fiscal year 2021. |

| 111. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020). Eliminate confinement as a response to probation rule violations. |

| 112. | Center for Children’s Law and Policy. (2016). Graduated responses toolkit: New resources and insights to help youth succeed on probation. |

| 113. | South Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice. (2019). Empowering our youth for the future: 2019 data resource guide. |

| 114. | Judicial Branch of Arizona – Maricopa County. (2020). Maricopa county juvenile probation department: Fiscal year 2020. |

| 115. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2015). Doors to DJS commitment: What drives juvenile confinement in Maryland? Powerpoint presentation. |

| 116. | National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. (2017). Resolution regarding juvenile probation and adolescent development. |

| 117. | National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. (2021). The role of the judge in transforming juvenile probation. |

| 118. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018), see note 93. |

| 119. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2018), see note 93; Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2019). Progress accelerates for eliminating confinement as a response to juvenile probation violations. |

| 120. | Sickmund, Sladky, & Kang (2023), see note 92. |

| 121. | Honeycutt, T., Zweig, J., Hague Angus, M., Esthappan, S., Lacoe, J., Sakala, L., & Young, D. (2020). Keeping youth out of the deep end of the juvenile justice system. Urban Institute, & Mathematica.; Annie E. Casey Foundation. (2020). Leading with race to reimagine juvenile justice. |

| 122. | Honeycutt et al. (2020), see note 121. |

| 123. | Annie E. Casey Foundation (2020), see note 121. |

| 124. | Annie E. Casey Foundation. Expansion of JDAI to the deep end toolkit. |

| 125. | National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. (2021). See note 117. |

| 126. | Scott MacDonald, interview with the author, April 5, 2023. Mr. MacDonald was formerly the Chief of Probation in Santa Cruz County, and he has subsequently worked as a technical assistance provider to juvenile courts and probation departments in Pierce County, Summit County, and Lucas County. |

| 127. | National Council of Juvenile and Family Court Judges. (2021). See note 117. |

| 128. | Santa Cruz County Probation Department (n.d.). Juvenile Division Annual Report 2022. |

| 129. | Santa Cruz County Probation Department (n.d.). See note 128. |

| 130. | Gina Castaneda, Deputy Probation Officer, Santa Cruz County Probation Department, interview with the author, September 1, 2023. |

| 131. | Castaneda. See note 130. |

| 132. | Castaneda. See note 130. |

| 133. | Castaneda. See note 130. |

| 134. | Jose Flores, Juvenile Division Director, Santa Cruz County Probation Department, interview with the author, September 1, 2023. |