Left to Die in Prison: Emerging Adults 25 and Younger Sentenced to Life without Parole

Two in five people sentenced to life without parole were 25 and under at the time of their conviction, despite irrefutable evidence that their younger age contributes to diminished capacity to comprehend the risk and consequences of their actions.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, Incarceration, Racial Justice

Executive Summary

Beginning at age 18, U.S. laws typically require persons charged with a crime to have their case heard in criminal rather than juvenile court, where penalties are more severe.1 The justification for this is that people are essentially adults by age 18, yet this conceptualization of adulthood is flawed. The identification of full criminal accountability at age 18 ignores the important, distinct phase of human development referred to as emerging adulthood, also known as late adolescence or young adulthood.2 Compelling evidence shows that most adolescents are not fully matured into adulthood until their mid-twenties.3

The legal demarcation of 18 as adulthood rests on outdated notions of adolescence. Based on the best scientific understanding of human development, ages 18 to 25 mark a unique stage of life between childhood and adulthood which is recognized within the fields of neuroscience, sociology, and psychology. Thus, there is growing support for providing incarcerated people who were young at the time of their offense a second look at their original sentence to account for their diminished capacity. A 2022 study found similar levels of public support for providing a second look at prison sentences for crimes committed under age 18 as for those committed under age 25.4

This brief proceeds in three sections:

- Analysis based on a newly compiled nationally representative dataset of nearly 30,000 individuals sentenced to life without parole (LWOP) between 1995 and 2017.

- Research review on adolescent brain development revealing that emerging adults share more characteristics with youth than adults.

- Judicial, legislative, and administrative reform updates in nine jurisdictions: California, Connecticut, Florida, Massachusetts, Michigan, Vermont, Washington, Washington, DC, and Wyoming.

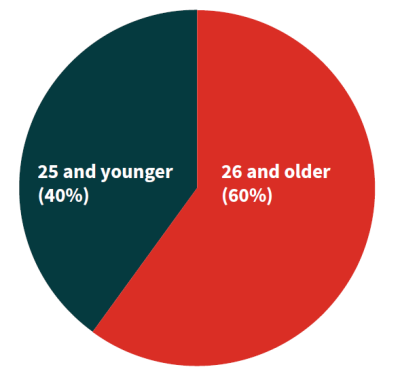

Two in five people–11,600 individuals–sentenced to LWOP between 1995 and 2017 were under 26 at the time of their sentence. In Michigan, Pennsylvania, and California, nearly half of those sentenced to LWOP were younger than 26. Nationally, the peak age at conviction was age 23, which is well within the period between youth and adulthood.

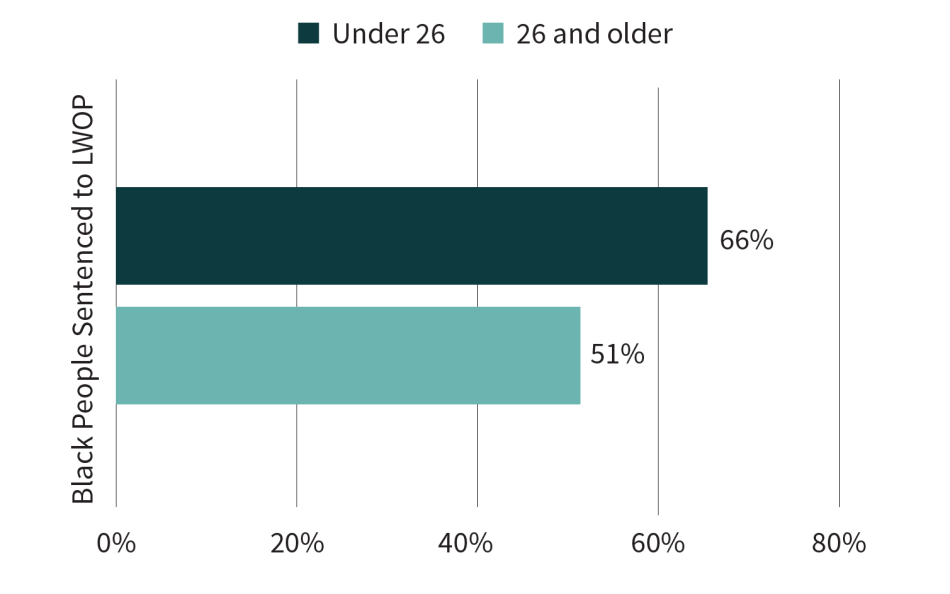

Moreover, two thirds (66%) of people under 26 years old sentenced to LWOP are Black compared with 51% of persons sentenced to LWOP beyond this age. As we show in this report, our analysis finds that being Black and young has produced a substantially larger share of LWOP sentences than being Black alone. This fact reinforces the growing understanding that extreme sentences disproportionately impact Black Americans.

The report’s findings support a recent sentencing trend recognizing emerging adulthood as a developmental stage; more than a dozen states have introduced or passed legislative reforms or adopted jurisprudential restrictions in recent years to protect emerging adults from extreme punishment. These reforms utilize the latest scientific understanding of adolescence and young adulthood to recognize emerging adulthood as a necessary consideration in assigning culpability.

In light of strong evidence showing the unique attributes of emerging adulthood, sentences that allow no review once adolescent development is concluded are especially egregious.5

Recommendation

Sentences that forbid review should never be imposed on individuals who have not yet reached adulthood.6 Life sentences with no option for parole review should be struck down entirely for emerging adults and should be limited to a maximum of 15 years. The Sentencing Project joins several national organizations in calling for special consideration of persons whose crime occurred before reaching adulthood.7

William Florentino

William Florentino was sentenced to LWOP in Massachusetts at 20-years-old following his participation in a robbery in 1977 in which his accomplice committed murder. Mr. Florentino was convicted of first degree murder and armed robbery because of his presence at the time of the murder, though he was not the triggerman, a lawful conviction in most states often referred to as felony murder, and punishable by LWOP in many states.

He has been in prison for 46 years and is now an elderly man. Over his decades of incarceration, Mr. Florentino has held steady employment, earned a college degree from Boston University, and devoted his life to self-reflection and spiritual growth. He is a trusted resident of the prison, permitted to work in areas of the facility restricted to those who have earned the highest level of independence. Though his life sentence forbids the accumulation of earned “good time,” he would have shaved many years off of his sentence if good time was allowed in his case.

Profile of Emerging Adults Sentenced to LWOP

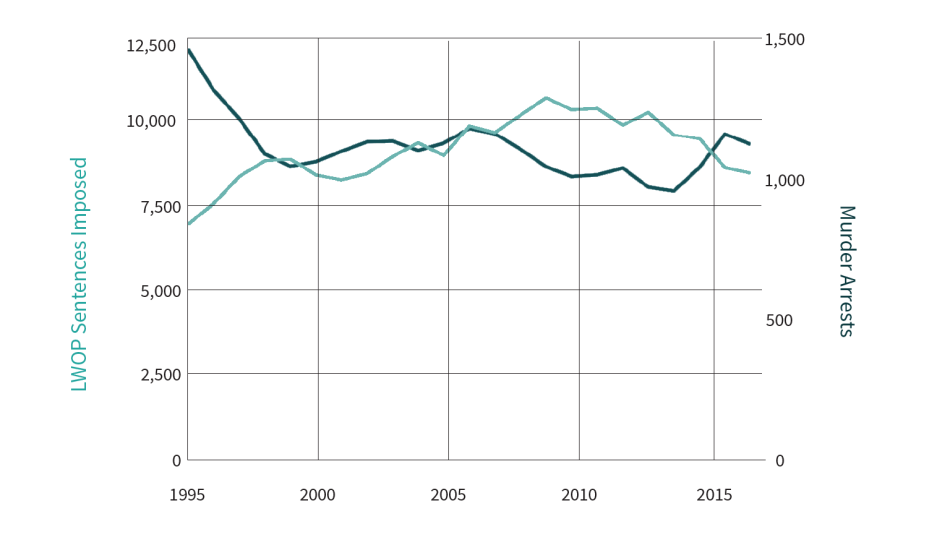

This analysis compiles sentencing data across 20 states inclusive of years 1995 through 2017. Though fewer than half the states, the people reflected in these data encompass 70% of the country’s life-without-parole (LWOP) population.8 Additionally, these years encapsulate the period of sharpest rise in mass incarceration overall, years during which making prison sentences longer to LWOP deter crime was mischaracterized as an effective crime reduction tool. These years also include those in which dehumanizing language against youth, especially Black youth, proliferated. These developments heavily influenced the use of life imprisonment, as illustrated by the remarkably continuous use of LWOP sentences for youth and young adults during a period of declining crime.

Age of Sentencing

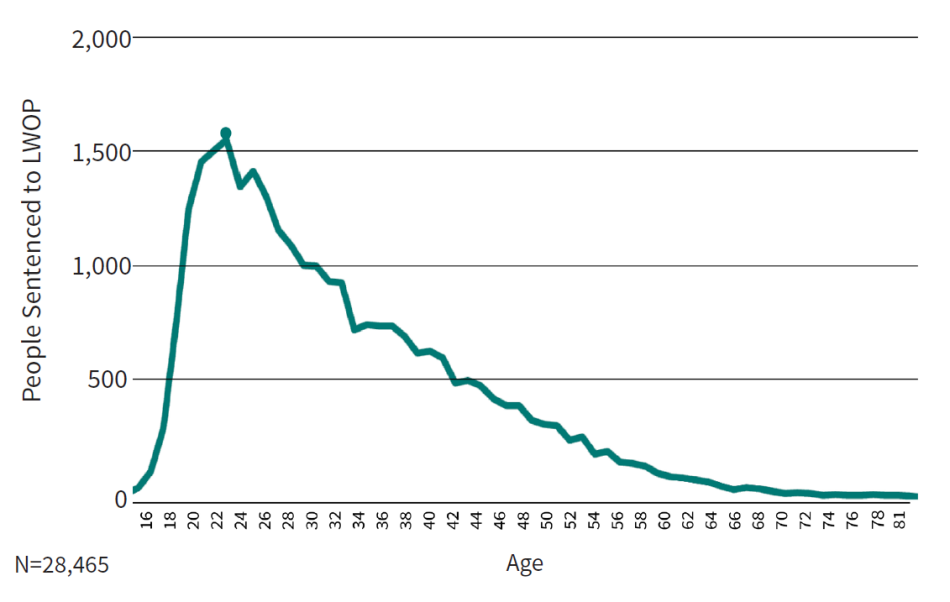

Among LWOP sentences imposed between 1995 and 2017, the peak age at conviction (i.e., the most common age at which these sentences were imposed) was 23 years old.9 Given that the time between age at offense and age at sentencing is approximately one year,9 we estimate the peak age of offense for people sentenced to LWOP during these years to be 22 years old.10 This is a critical finding, as this age falls well within the standard boundaries of emerging adulthood, as does the age at which they committed their offense.

FIGURE 1. Age at Sentencing Among People Sentenced to LWOP Between 1995 and 2017

We also find a significant decline in the number of people who received an LWOP sentence after their early twenties. This matches what we already know about age-crime patterns; there is a large body of evidence showing a rapidly declining likelihood to commit violent crimes (including murder) with age. Dozens of studies find that the typical ages at which people are most likely to engage in violence climb from the late teenage years to one’s twenties before dramatically falling throughout one’s mid-to late-twenties.11

FIGURE 2. People Sentenced to LWOP Between 1995 and 2017, by Grouped Age

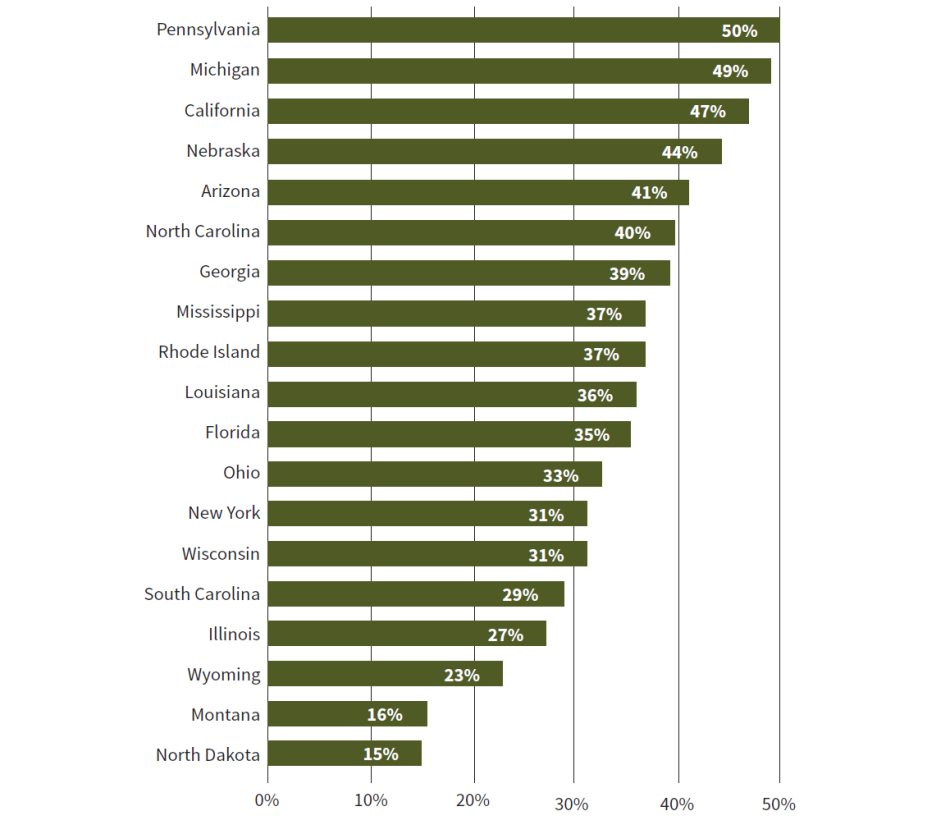

Two in five people sentenced to LWOP between 1995 and 2017 were younger than 26 when told they would die in prison, amounting to 11,613 people across these 20 states. A closer look at the state level (Figure 3) shows significant variation, with this proportion ranging from 15% to 50%. Pennsylvania (50%) leads the nation, closely followed by Michigan (49%) among states whose share of persons sentenced to LWOP were younger than 26 years of age, followed by California (47%).12

FIGURE 3. Emerging Adults Sentenced to LWOP between 1995 and 2017

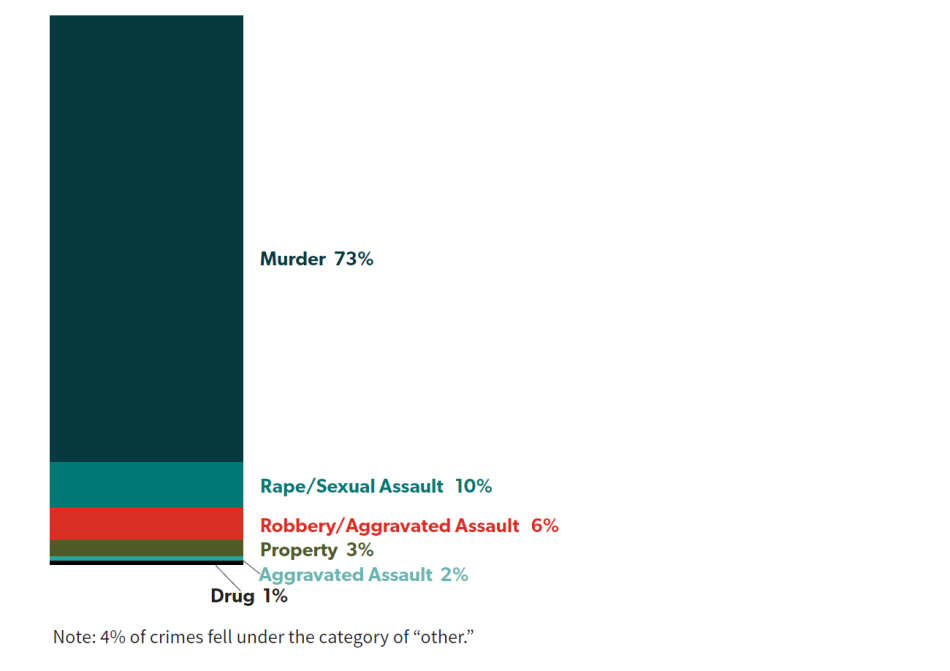

Crime of Conviction

The Sentencing Project’s most recent national census of individuals serving LWOP found that 74% had been convicted of murder.13 In the 20-state dataset examined for this report, which encompasses the vast majority of people serving LWOP nationally, we find that 73% had been convicted of first degree, second degree, or another type of non-negligent murder (Figure 4). When examining sentencing age and crime of conviction at the individual-level by sentencing age and crime of conviction, we observe the peak age at which most people convicted of murder were sentenced to LWOP was 22 years old.

We also find that the peak age at sentencing for crimes of a sexual nature to be somewhat higher, which is in line with the data and literature showing that the age of onset among those who commit these crimes tends to be later than other crimes of violence. Indeed, 88% of the people convicted of a sexual assault or rape in this analysis were over 25 years old at sentencing. Existing research supports the claim that people convicted of sexual offenses have a later onset, but still follow a similar pattern of precipitous decline in early-to-mid adulthood.14

FIGURE 4. Conviction Offenses Among People Sentenced to LWOP from 1995 through 2017

Race

Racial and ethnic disparities are readily apparent in criminal sentencing data and grow with lengthier sentences.15 More than half (55%) of all people serving LWOP in 2020 were Black.16 Though they arise largely from disparate treatment by race, particularly bias against Black people,17 for violent crimes these disparities are also associated with differential engagement in crime.18 Violent crime cannot be resolved without considerable and sustained investments in disadvantaged urban areas that are predominantly Black, and which have been chronically neglected.19

Among emerging adults in this dataset, the racial disparity is significantly greater, as depicted below (Figure 5). Being Black and young has produced a substantially larger share of LWOP sentences than being Black alone. Two thirds (66%) of emerging adults sentenced to LWOP are Black. Among people sentenced to LWOP in adulthood, 51% are Black. Though we cannot make causal connections from these data alone, racism clearly plays a role in Black people’s experience of the criminal legal system from start to end. Studies find that Black children as young as 10 years old are mistaken as being older than they actually are, less likely to be given the benefit of the doubt, and seen as more culpable for similar actions as white or Latinx youth.20 By age 23, 30% of Black males in America have been arrested, compared to 22% of non-Black males.21 It would make sense that these factors contribute to the racial disparities we observe among those sentenced to LWOP as well.

FIGURE 5. Black People Sentenced to LWOP by Grouped Age

Sentencing Trends

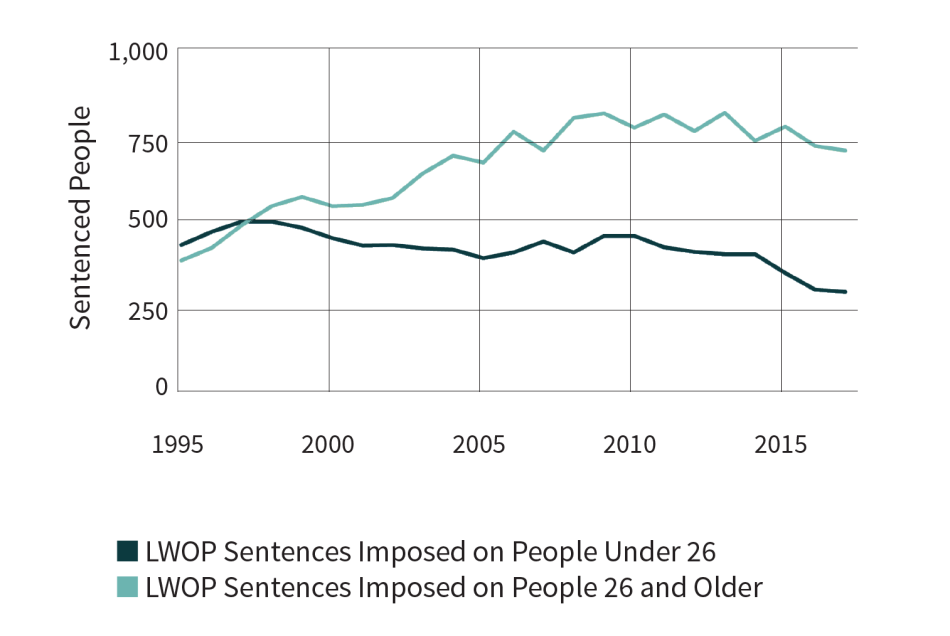

LWOP sentences rose considerably in the 1990s and early 2000s amid a declining violent crime rate. In more recent years, states have reduced their use of LWOP.22 Since 2010, there has been a greater decline in the number of emerging adults receiving LWOP sentences than has been the case among adults. LWOP sentences imposed on people under age 26 peaked in 1998 but stabilized until 2009, since which time the imposition of these sentences declined 37%. LWOP sentences imposed on people 26 and older continued to rise until 2013 but dropped 14% between 2014 and 2017.

FIGURE 6. LWOP Sentencing Trends, by Grouped Age, 1995-2017

Conclusions for the divergent sentencing patterns cannot be explained definitively, but it is plausible that the recent Supreme Court rulings concerning the cruelty of LWOP sentences imposed on youth under age 18 have had a collateral benefit for late adolescents charged with serious crimes as well. Judges and prosecutors may be proactively considering wider age ranges and opting for non-LWOP sentences in these cases based on an evolving standard of decency and scientific consensus.

Neuroscientific Understanding of Emerging Adults

Clark University Department of Psychology’s Senior Research Scholar Jeffrey Jensen Arnett is credited with originating the term “emerging adulthood” to define the stage of life between adolescence and adulthood, distinguishing it as its own life stage.23 His work is widely cited as a key resource in understanding the period of late adolescence, contributing to the perspective that emerging adulthood is marked by identity exploration and risk taking.24

Basing much of its reasoning on the neuroscientific evidence that executive functioning is diminished among those 17 and younger, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in 2005 that death sentences were unconstitutional for them.25 In considering what age to mark the difference between youth and adulthood, the Supreme Court agreed with the petitioner’s argument that age 18 was ideal because it was “the point where society draws the line for many purposes between childhood and adulthood.”25 Subsequent Supreme Court rulings (Graham v. Florida,27 Miller v. Alabama,28 and Montgomery v. Louisiana29.) have benefitted roughly 2,000 individuals who were under 18 at the time of their crime and had received LWOP for a nonhomicide offense or as a mandatory minimum sentence.30

In Miller v. Alabama the justices conceded that age 18 was a somewhat arbitrary number, writing “the qualities that distinguish juveniles from adults do not disappear when an individual turns 18.”31 Additionally, a major national report produced by the National Academy of Sciences (NAS) concluded that it would be “arbitrary in developmental terms to draw a cut-off line at age 18.”32

The reasoning for identifying age 18 in these cases rested on a notion of adulthood that is not recognized among experts and is increasingly rejected by society as well. A large body of research finds that young adults are still undergoing important developments through the end of their teenage years and at least until their mid-20s. These cognitive, emotional, and physical developments occurring in the human brain over these years are consequential to behavior.33 In fact, neurobiological and adolescent developmental psychology research finds that late adolescents share more characteristics with children and teenagers than with adults. This is particularly evident in emotionally charged situations.34

Nevertheless, a range of allowances based on expectations of maturity commences at age 18. At this age, most individuals can vote, sign a contract, serve on a jury, drive independently, and join the military without parental permission.35 For some, age 18 marks the point at which teenagers move out of their childhood homes, live independently and begin college or full-time work. For these societal reasons and based loosely on nascent scientific understanding of age 18 as an important life milestone, the U.S. Supreme Court in Roper v. Simmons labeled death sentences imposed on persons under 18 as unconstitutional.25 It is also the case that the petitioner himself was 17 at the time, which likely contributes to the limitation of the ruling to people under 18. But the extension of this thinking to age 18 being the legal cutoff after which there can be total criminal culpability does not follow either logic or science.

Incorporation of Neuroscience into Understanding of Criminal Behavior Among Emerging Adults

Authors of the 2019 NAS report concluded that emerging adults are more likely to engage in risky, impulsive, and sometimes criminal behavior because they are not yet fully developed.37 The report explains: “most late adolescents will naturally grow out of this phase and fundamentally change their behavior, including through neurological growth that enhances their capacity for reasoned decision-making under stress and future-looking orientation, and are uniquely amenable to rehabilitation.”38

The development from adolescence to “late adolescence” or emerging adulthood is marked by lower levels of emotional control and higher levels of impulsive actions. These lead to suboptimal decisions that can include violence, especially when a young person’s childhood is saturated with individual or community violence. Between the ages of 18 and 25, individuals have a greater propensity to take actions in emotionally charged situations with high risk or high reward. Neuroscientists often refer to this period as “hot cognition.”39 Cold cognition, by comparison, is marked by thinking abilities in calm situations.

Developmental psychology expert and Temple University professor Laurence Steinberg refers to the analogy of driving a car to help explain the differences between diminished sections of the brain and those that are fully developed. Adolescence is a time when the “accelerator” is pressed to the floor, but a good “braking system” is not yet in place.40

Societal Definitions for Adulthood

American society associates adulthood with financial independence, educational completion, or getting married, some of which do begin around age 18.41 But these notions of adulthood may be outdated; today, these markers of independence are far more uncertain, in part due to changed economic realities, such as the cost of housing and the need for academic credentials in many fields that were not required during more agrarian eras. As a result, the social markers between youth and adulthood are more nuanced than previously understood.42

Consequently, emerging adults share many key developmental characteristics with adolescents under age 18. Those who commit a violent crime are also experiencing a challenging and transitory life period that is often made more difficult by trauma and other adverse life experiences;43 and these individuals have tremendous potential for growth and opportunity with the proper support.44

Judicial and Legislative Recognition of Emerging Adults

Legislative Reforms

State courts and legislatures have introduced or implemented expansive legal reforms that protect youth from the extremities of the adult legal system, including:

- limitations on trying youth under 18 in adult criminal court;

- special protections in the juvenile and adult courtrooms for youth,

- expanded sentencing and parole policies accounting for young age; and

- developmentally sensitive correctional programs both in facilities and in communities.

With the wider entrenchment and advances of adolescent neuroscience, these reforms are likely to gain greater acceptance. Still, jurisprudence since Miller shows minimal success and sometimes contradicting rulings45 across states in extending its decision to those above 18.

Legislatively, jurisdictions are tackling the task of providing late adolescents the opportunity for a second look based on the reduced culpability associated with their stage of development.

Washington, DC passed legislation in 2020 to provide people who committed crimes when they were under 25 years old a chance at sentence reduction. Eligibility to file a petition begins after 15 years of imprisonment and is permitted a total of three times with a three-year wait after an unsuccessful petition.46 Judges are required to consider young age and childhood abuse and to examine efforts at rehabilitation, disciplinary infractions, and overall fitness to return to society.47

In 2019, the Illinois legislature enacted House Bill 531, which allows parole review at 10 or 20 years into a sentence for most crimes, exclusive of sentences to LWOP, if the individual was under 21 at the time of the offense.48 Those going before a parole board now have a right to an attorney and at least one member of the board must hold expertise on the issue of adolescent development. In its review process, the parole board is required to give great weight to the hallmark features of youth and subsequent growth in making its parole decision. The bill was not enacted retroactively.

In January 2023, Illinois Governor J.B. Pritzker signed into law a bill that ends LWOP for most individuals under 21 years old, permitting review after 40 years.49 Though the bill was not retroactively applied, in the same month Illinois Senator Seth Lewis introduced legislation that would make the 2019 and the 2023 laws retroactive.50 If these were to pass, it would allow the possibility of early release of as many as 3,000 people.51

In July 2020, Vermont Governor Phil Scott signed Senate Bill 232 into law, making it the first state to retain people under 19 years old in juvenile court, with plans to add 19- and 20-year-olds in later years. In most states, the juvenile justice system retains jurisdiction over defendants convicted in the juvenile system up to their 21st birthday.52

Judicial Reforms

In 2021, Michigan’s Supreme Court held that mandatory LWOP sentences for 18-year-olds violate the Michigan Constitution.53 The Court highlighted that “late-adolescence” is a pertinent stage in development reflected by major changes in one’s brain and behavior, noting,

The key characteristic of the adolescent brain is exceptional neuroplasticity, which is a critical period of cognitive development for young adults…late adolescents are hampered in their ability to make decisions, exercise self-control, appreciate risks or consequences, feel fear, and plan. Thus, this period of late adolescence is characterized by impulsivity, recklessness, and risk-taking.54

In 2021, Washington became the first state to extend the constitutional protection against mandatory LWOP sentences to young people over 17 years of age. The ruling states, in part:

…a scientific consensus has developed that demonstrates that young people continue to develop neurologically until age 26. The legislature finds that until then, young people are less able to make decisions for themselves, are more impulsive, and more susceptible to peer pressure.55

The Supreme Court of Washington held that the state’s aggravated murder statute, which carries a mandatory LWOP penalty, was unconstitutional as applied to individuals between the ages of 18 and 21 years old, citing a range of neuroscientific findings that there is no meaningful difference in maturity between 17 and 18-year-olds, and that mental development continues into a person’s 20s.

A Massachusetts Superior Court judge ruled in 2020 that it is unconstitutional to automatically sentence youth under the age of 21 to life without parole. As of the writing of this report, this matter is on appeal in the state’s supreme court (Commonwealth v. Mattis).56 An amicus brief submitted by a group of neuroscientists, psychologists, and criminal legal reform scholars in support of the defendant includes this statement: “From a scientific perspective, a person’s 18th birthday is not a rational dividing line for justifying LWOP because the brain develops and changes rapidly across all relevant metrics long after age 18.”57

In late 2023, California’s Supreme Court is scheduled to hear arguments on behalf of petitioner Tony Hardin, who has been serving LWOP since 1990 for a crime committed when he was 25 years old. Hardin’s legal team argues that the adolescent brain science guiding existing sentence allowances should be extended to sentences of LWOP for youth up to age 26.58 The state currently identifies individuals under 26 as “youth offenders” and thus eligible for a youth offender parole hearing for crimes including those that result in life-with-parole. It also allows for a second look for those who had been sentenced to LWOP for crimes committed when under 18. However, California does not currently allow mitigation for or delineation of “youth offender status” for persons sentenced to life-without-parole for crimes committed when over 18 years old.59

Administrative Reforms

Not all changes must be made in the courts or via statutory reform; administrative modifications can produce change. In Wyoming, “youthful offender” programs were revised in 2021 to offer reduced and alternative sentencing for adolescents who are convicted of felonies, extending their eligibility to 30 years old.60

In 2022, Connecticut’s Board of Pardons and Parole commuted the sentences of 11 people who had been under 25 at the time of their crime and served lengthy terms already. The Board’s decision was in direct response to the growing consensus that emerging adults should be afforded a second look.61

Reforms are also in progress in other cases as part of the growing trend of legislation acknowledging “emerging adults” and youth past the age of 18. For example, in New York active bills are attempting to increase the age of those who receive youthful offender status to 22 and 25.62 In West Virginia, an active bill, the “Second Look Sentencing Act,” reconsiders an incarcerated person’s sentence after 10 years. Notably, it requires the consideration of age and resulting diminished capability at the time of the offense, as well as, “…relevant data on age and declining criminality.”63 Moreover, in Colorado, a 2019 bill passed that delegated the Commission on Criminal and Juvenile Justice to study the use of juvenile justice services and systems for young adults, defined as those 18 through 24 years of age. The bill specifically stated the need to study the established brain science research relevant to young adults.64 Further, Colorado passed, in 2021, an act that expanded specialized program eligibility usually reserved for juveniles, to adults who were under 21 when they committed a felony.65

International Context

The United States holds an estimated 40% of the world’s life-sentenced population, including 83% of those serving LWOP. Criminal legal systems in other industrialized nations recognize this important stage of emerging adulthood as one requiring extra consideration.66 Most nations do not allow youth who were under 18 at the time of their crime to be sentenced to LWOP for any crime, and many also exclude LWOP for adults. Where parole-eligible life sentences are allowed, they are rarely used for youth.67 Among nations that impose sentencing restrictions for youth under 18 are several that also limit the use of life imprisonment for emerging adults:

- In Germany, people between ages 18 and 20, courts may impose a fixed term of 10 to 15 years instead of the maximum life sentence. Also in Germany, the Juvenile Justice Act has allowed, since 1953, for 18- to 21-year-olds to receive the same youthful consideration as those under age 18, if they determine that the individual is still developing morally and psychologically.

- In Austria, people who are 18 to 21 years old cannot serve over 15 years in prison; people 21 and older can serve up to 20 years.

- In Hungary and Bulgaria, persons must have been at least 20 years of age at the time of the offense to receive a life sentence.

- In Serbia, a country that does not allow life imprisonment but permits sentences as long as 40 years, sentences this long are restricted to those who are 21 years of age or older.68

Conclusion

Multidisciplinary research on the course of development from childhood into adulthood converges on the conclusion that this developmental course does not reach its apex at 18, but instead continues until one’s mid-20s, at a minimum.69 Yet the criminal legal system views people under 26 as if they were fully developed adults. The treatment of young adults as if they are fully matured adults is especially cruel for those facing sentences that allow no possibility for release, the focus of this report.70

Objective measures of society’s standards of decency show that death-by-prison sentences are cruel for people over 18 for the same reasons as they are for people under 18. A justice system that takes a limited view of only the seriousness of a crime and neglects to afford greater weight to late adolescence as a mitigating circumstance fails on moral and ethical grounds. On this topic and writing for the Supreme Court in Solem v. Helm, Justice Powell wrote, “the concept of proportionality is central to the Eighth Amendment.”71

Legal distinctions by age are too often influenced by shifts in political landscape and the conventional wisdom of the time, but evidence and research should be the guide. Based on this clear finding of emerging adulthood’s shared characteristics with individuals who are under 18–an age for which exclusions already apply–states should, at a minimum, eliminate the use of LWOP for people 25 and younger entirely. The public agrees that there is no meaningful difference in the assignment of culpability between youth and emerging adults.72

Moreover, people sentenced as a youth or as an emerging adult should be afforded a review within the first ten years of their sentence and a sentence cap at 15 years. This reform is a starting point in reorienting the justice system toward one that applies punishments only in proportion to both the crime and the culpability of the person who committed the crime.

Methodology

In 2018, The Sentencing Project and the Wilson Center for Science and Justice at Duke University submitted requests to select state departments of corrections based on the size of their LWOP population, prioritizing those states with large populations of individuals serving life-without-parole sentences. We requested individual-level data including race, ethnicity, sex, date of sentence, and date of offense, regarding people who had been sentenced to life-without-parole, annually, from 1990 to 2018. We received usable data from 20 states, comprising an estimated 70% of the national LWOP population.73 The years are confined to the range of 1995 through 2017 because we successfully obtained data from each state for each of these years. Appendix A provides a descriptive overview of the dataset used in this report.

Readers should note that this dataset includes 529 people who were sentenced to LWOP for crimes committed when they were under age 18, sometimes referred to as “JLWOPs.” It is impossible to further examine these cases without reviewing court records. As discussed in this report and extensively elsewhere, the U.S. Supreme Court rulings invalidated the original sentences of approximately 2,000 people: some have been released, some have been resentenced to lower terms, and others have been resentenced to LWOP.

Appendices

A. Descriptive Statistics

| Crime | Peak Age | Mean | Median | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murder | 22 | 31 | 28 | 14-85 |

| Rape/Sexual Assault | 36 | 39 | 38 | 17-81 |

| Robbery | 23 | 31 | 29 | 16-74 |

| Property Offense | 26 | 33 | 31 | 19-63 |

| Aggravated Assault | 26 | 33 | 31 | 18-63 |

| Kidnapping | 24* | 34 | 32 | 16-65 |

| Drug Offense | 30 | 30 | 34 | 19-60 |

| Total | 28,368 | 100% | 23 |

Note: Kidnapping was bimodal with a second mode at age 26.

| Race/Ethnicity | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| White | 7,725 | 30.6% |

| Black | 14,269 | 56.5% |

| Latinx | 1,813 | 7.2% |

| Other | 1,447 | 5.7% |

| Total | 25,254 | 100.0% |

| Sex | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Men | 25,036 | 96.4% |

| Women | 936 | 3.6% |

| Total | 25,972 | 100.0% |

| Years Served as of January 2023 | Count | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Less than 10 Years | 7,322 | 24.9% |

| 10-20 Years | 14,656 | 49.9% |

| More than 20 Years | 7,390 | 25.2% |

| Total | 29,368 | 100.0% |

B. Murder Arrests and LWOP Sentences in 20 States

| 1. | Georgia, Texas, and Wisconsin automatically process all people under 18 charged with a crime in criminal rather than juvenile court. All states allow or require some people under 18 to be prosecuted in the adult court system. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Arnett, J. (2000). Emerging adulthood: A theory of development from the late teens through the twenties. American Psychologist, 55, 469-480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.5.469. |

| 3. | Arnett, J. (2000), see note 2. |

| 4. | Hannan, K. R., Cullen, F. T., Graham, A., Lero Jonson, C., Pickett, J. T., Haner, M., & Sloan, M. M. (2023). Public support for second look sentencing: Is there a Shawshank Redemption effect? Criminology and Public Policy, 22(2), 263-292. https://doi.org/10.1111/1745-9133.12616. |

| 5. | This brief focuses on life-without-parole sentences because of their unique requirement of death by incarceration with no viable option for review or release. |

| 6. | Though this briefing paper addresses issues of unique concerns to older adolescents, The Sentencing Project advocates for capping sentences at a maximum of 20 years with a possibility for release beforehand, and a second look at the original sentence within the first 10 years of a person’s sentence for all individuals. Such second look policies allow for recognition of rehabilitation and maturity that emerge within the individual. For a longer discussion of this general policy recommendation, see Ghandnoosh, N. (2021). A second look at injustice. The Sentencing Project. |

| 7. | Organizations including the Columbia Justice Lab, Juvenile Law Center, Vera Institute of Justice, and the American Psychological Association, have worked extensively through research and/or advocacy to curb the harshest sentences for juveniles and emerging adults. See, for example: Parker, S. S., Chester, L., & Schiraldi, V. (2019). Emerging adult justice in Illinois: Towards an age-appropriate approach. Columbia Justice Lab.; Lindell, K. U., & Goodjoint, K. L. (2020). Rethinking justice for emerging adults: Spotlight on the Great Lakes Region. Juvenile Law Center.; Fountain, E., Mikytuck, A., & Woolard, J. (2021). Treating emerging adults differently: How developmental science informs perceptions of justice policy. Translational Issues in Psychological Science, 7(1), 65–79. https://doi.org/10.1037/tps0000248. |

| 8. | Nellis, A. (2021). No end in sight: America’s enduring reliance on life imprisonment. The Sentencing Project. |

| 9. | Based on a smaller sample of five states that provided date of offense as well as date of sentence, we calculated the difference in time between the two to be about one year. |

| 10. | Because most states provided a date of sentencing rather than date of offense, we rely on sentencing data for this report. |

| 11. | Snyder, H. (2012). Arrest in the United States 1990-2010. Bureau of Justice Statistics. Figure 4. |

| 12. | Vermont reported not having any individuals in this range of years who were under 26 when they were sentenced. |

| 13. | Nellis, A. (2021), see note 8. The remaining crimes for which people were serving LWOP sentences are sexual assault/rape (9%), robbery (5%), aggravated assault (1%), or a drug offense (3%). The category of “murder” includes first degree, second degree, and nonnegligent homicide. |

| 14. | Crookes, R. L., Tramontano, C., Brown, S. J., Walker, K., & Wright, H. (2022). Older individuals convicted of sexual offenses: A literature review. Sexual Offenses, 34(3), 341-371. https://doi.org/10.1177/10790632211024244. |

| 15. | Ghandnoosh, N., & Nellis, A. (2023). How many people are spending over a decade in prison? The Sentencing Project. |

| 16. | Nellis, A. (2021), see note 8. |

| 17. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2014). Race and punishment: Racial perceptions of crime and support for punitive policies. The Sentencing Project. |

| 18. | Beck, A., & Blumstein, A. (2017). Racial disproportionality in U.S. state prisons: Accounting for the effects of racial and ethnic differences in criminal involvement, arrests, sentencing, and time served. Journal of Quantitative Criminology, 34, 853-883. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10940-017-9357-6. |

| 19. | Muhammad, K.G., Western, B., Negussie, Y., & Backes, E. (2022). Reducing racial inequality in crime and justice: Science, practice, and policy. National Academies Press. |

| 20. | Goff, P. A., Culotta, C. M., DiTomasso, N. A., Jckson, M. C., Allison, B., & DiLeone, A. L. (2014). The essence of innocence: Consequences of dehumanizing Black children. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106(4), 526-545. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035663. |

| 21. | Brame, R., Turner, M.G., Paternoster, R., & Bushway, S.D. (2012) Cumulative prevalence of arrest from ages 8 to 23 in a national sample. Pediatrics, 129, 21–27. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-3710; Brame, R., Bushway, S.D., Paternoster, R., & Turner, M.G. (2014). Demographic patterns of cumulative arrest prevalence by ages 18 and 23. Crime and Delinquency, 60(3), 471-486. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011128713514801. |

| 22. | We also compared murder rates in these 20 states to LWOP sentencing patterns and did not observe any discernible trends between the two. See Appendix B. |

| 23. | Arnett, J. (2000), see note 2; Arnett, J. (1992). Reckless behavior in adolescence: A developmental perspective. Developmental Review, 12(4), 339–373. https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(92)90013-R. |

| 24. | Casey, B. J., Simmons, C., Somerville, L., & Baskin-Sommers, A. (2022). Making the sentencing case: Psychological and neuroscientific evidence for expanding the age of youthful offenders. Annual Review of Criminology, 5(1), 321–343. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-criminol-030920-113250. |

| 25. | Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005). |

| 26. | Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005). |

| 27. | Graham v. Florida, 560 U.S. 48 (2010). |

| 28. | Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. 460 (2012). |

| 29. | Montgomery v. Louisiana, 136 S. Ct. 718,. 733 (2016). |

| 30. | Rovner, J. (2023). Juvenile life without parole: An overview. The Sentencing Project. |

| 31. | Miller v. Alabama, 567 U.S. at 465 (2012). |

| 32. | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25388; See also, Scott, E., Bonnie, R.J., & Steinberg, L. (2016). Young adulthood as a transitional legal category: Science, social change, and justice policy. Fordham Law Review, 85, 641-644. |

| 33. | Bigler, E. (2021). Charting brain development in graphs, diagrams, and figures from childhood, adolescence, to early adulthood: Neuroimaging implications for neuropsychology. Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, 7(1-2), 27–54. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-021-00099-6; Casey, et al. (2022), see note 25; Insel, C., Tabashneck, S., Shen, F. X, Edershim, J. G., & Kinscherff, R. T. (2022). The science of late adolescence: A guide for judges, attorneys and policy makers. Center for Law, Brain & Behavior at Massachusetts General Hospital.; Cohen, K., Breiner, L., Steinberg, R., Bonnie, E., Scott, K., Taylor-Thompson, M., Rudolph, J., Chein, J., Richeson, A., Heller, M., Silverman, D., Dellarco, D., Fair, A., Galván, & Casey, B.J. (2016). When is an adolescent an adult? Assessing cognitive control in emotional and nonemotional context. Psychological Science. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797615627625; Gur, R. C. (2021). Development of brain behavior integration systems related to criminal culpability from childhood to young adulthood: Does it stop at 18 years? Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, 7, 55-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-021-00101-1; Haney, C., Baumgartner, F. R., & Steele, K. (2022). Roper and race: The nature and effects of death penalty exclusions for juveniles and the “Late adolescent class.” Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, 8(4), 168–177. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-022-00134-0; Shust, K. (2014). Extending sentencing mitigation for deserving young adults.” The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 104(3), 667–704; Steinberg, L. (2017). Adolescent brain science and juvenile justice policymaking. Psychology, Public Policy, and Law, 23(4), 410–420. https://doi.org/10.1037/law0000128. |

| 34. | Aamodt, S., & Wang, S. (2011). Welcome to your child’s brain: how the mind grows from conception to college. American Psychological Association. (2022). APA resolution on the imposition of death as a penalty for persons aged 18 through 20, also known as the late adolescent class.; Gur, R. C. (2021), see note 34; Cohen, et al. (2016), see note 34. |

| 35. | Lindell & Goodjoint (2020), see note 7. |

| 36. | Roper v. Simmons, 543 U.S. 551 (2005). |

| 37. | National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2019). The promise of adolescence: Realizing opportunity for all youth. National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/25388. |

| 38. | Brief of Amici Curiae Neuroscientists, Psychologists, and Criminal Justice Scholars in Support Defendant-Appellant Sheldon Mattis and Affirmance. https://jlc.org/sites/default/files/attachments/2022-12/2022.12.16%20Neuroscientists%2C%20Psychologists%20%26%20Crim.%20Just.%20Scholars%20Amicus.pdf page 2. |

| 39. | Cohen, et al. (2016), see note 34; Steinberg, L. (2005). Cognitive and affective development in adolescence. Trends in Cognitive Science, 69, 72-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2004.12.005. |

| 40. | Steinberg, L. (2009). Should the science of adolescent brain development inform public policy? American Psychology, 64, 739. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.64.8.739. |

| 41. | There is some degree of state variation on these markers of adulthood, but these are generally the case. |

| 42. | A growing literature exists on the topic of life-course, role adoption, and desistance from crime. See, for example: Leverents, A., Chen, E. Y., & Christian, J. (Eds.). (2022). Beyond recidivism: New approaches to research on prison reentry and reintegration. New York University Press. |

| 43. | Nellis, A. (2012). The lives of juvenile lifers: Findings from a national survey. The Sentencing Project. http://www.jstor.org/stable/resrep27344. |

| 44. | Schiraldi, V., Western, B., & Bradner, K. (2015). Community-based responses to justice-involved young adults. Harvard Kennedy School.; Bernard, K., Schwager, D., & Sitney, M. (2020). Reimagining probation and parole for young adults in the United States. European Journal of Probation, 12(3), 200–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/2066220320981180. |

| 45. | Shen, F. X., McLuski, F., Shortell, E., Bellamoroso, M., Escalante, E., Evans, B., Hayes, I., Kimmey, C., Lagan, S., Muller, M., Near, J., Nicholson, K., Okeri, J., Okoli, I., Rehmet, E., Gertner, N., & Kinscherff, R. (2022). Justice for emerging adults after Jones: The rapidly developing use of neuroscience to extend Eighth Amendment Miller protections to defendants age 18 and older. New York University Law Review, 97(30), 101-126. |

| 46. | B. 24-416 “Revised Criminal Code Act of 2021,” 24th Council, (D.C. 2020) (enacted). https://legiscan.com/DC/bill/B24-0416/2021. |

| 47. | Hannan, et al. (2023), see note 4. |

| 48. | H.B. 531, 102nd Gen. Assembly, (Illinois, 2019) (enacted). https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=0531&GAID=14&GA=100&DocTypeID=HB&LegID=100727&SessionID=91; This law excluded from consideration persons convicted of more eggregious, aggravated forms of murder or sexual assault. Persons serving sentences of LWOP and those exceeding 40 years imposed on juveniles under 18 were also excluded. |

| 49. | H.B. 1064,Public Act 102-1128, (Illinois 2023) (enacted). https://www.ilga.gov/legislation/publicacts/fulltext.asp?Name=102-1128. |

| 50. | S.B. 2073, 103rd Gen. Assembly, (Illinois 2023) https://ilga.gov/legislation/billstatus.asp?DocNum=2073&GAID=17&GA=103&DocTypeID=SB&LegID=146946&SessionID=112. |

| 51. | Rivera, A. (2023). Illinois abolishes Life without Parole sentences for children; legislators introduce bill to make youthful parole retroactive. Restore Justice Illinois. |

| 52. | Juvenile Justice, Geography, Policy, Practice & Statistics (2023). Jurisdictional boundaries. National Center for Juvenile Justice, MacArthur Foundation. |

| 53. | People v. Parks, 226 N.W.2d 710,57 Mich. App. 738 (Mich. 2021). https://www.courts.michigan.gov/4a21a7/siteassets/case-documents/opinions-orders/msc-term-opinions-(manually-curated)/21-22/parks-op.pdf. |

| 54. | People v. Parks Syllabus Op. 2, 226 N.W.2d 710,57 Mich. App. 738 (Mich. 2021). https://www.courts.michigan.gov/4a21a7/siteassets/case-documents/opinions-orders/msc-term-opinions-(manually-curated)/21-22/parks-op.pdf. |

| 55. | In re Pers. Restraint of Monschke, 482 P.3d 276 (Wash. 2021). https://case-law.vlex.com/vid/in-re-monschke-no-887598032. |

| 56. | Commonwealth v. Mattis, 28 U.S.C. § 2254 (Mass. 2023). https://dockets.justia.com/docket/massachusetts/madce/1:2023cv10854/256159. |

| 57. | Brief of Amici Curiae Neuroscientists, Psychologists, and Criminal Justice Scholars in Support of Defendant-Appellant Mr. Parks in People v. Parks, 226 N.W.2d 710,57 Mich. App. 738 (Mich. 2021). |

| 58. | People v. Hardin, 84 Cal. App. 5th 273 (California 2022). https://casetext.com/case/people-v-hardin-113. California law permits a Franklin hearing to allow defendants under 18 to preserve evidence of youth-related mitigating factors for purposes of a youthful offender parole hearing to be held in the future pursuant to Penal Code section 3051.2 (See People v. Franklin (2016) 63 Cal.4th 261 (Franklin).) Most juvenile and emerging adult defendants are permitted a hearing, but those sentenced to LWOP are not. |

| 59. | Youth Offender Parole Hearings, S.B. 261, Chapter 471, (California Statute 2015) (enacted). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201520160SB261; Youth Offender Parole Hearings, S.B. 260, Chapter 312, (California Statute 2014) (enacted). https://legiscan.com/CA/text/SB260/id/885854; Youth Offender Parole Hearings, A.B. 1308, Chapter 675, (California Statute 2017) (enacted). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billTextClient.xhtml?bill_id=201720180AB1308; Sentencing, S.B. 9, Chapter 828, (California 2012) (enacted). https://leginfo.legislature.ca.gov/faces/billNavClient.xhtml?bill_id=201120120SB9. |

| 60. | WY Stat § 7-13-1002 (2022).; WY Stat. § 7-13-1003 (2022). |

| 61. | Lyons, K. (2023, January 27). CT parole board shortens sentences of 11 men convicted of murder. CT Mirror. https://ctmirror.org/2022/01/21/parole-board-shortens-sentences-of-11-men-who-committed-crimes-when-they-were-young/. |

| 62. | S. 5749, 2021-2022 Regular Sessions (NY 2021). https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2021/S5749A; A. 5871, 2019-2020 Regular Sessions (NY 2019). https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2019/A5871; S. 292, 2021-2022 Regular Sessions (NY 2021). https://legislation.nysenate.gov/pdf/bills/2021/S282. |

| 63. | H.B. 2962, §62 – 11 A- 1 B (West Virginia 2023). http://www.wvlegislature.gov/Bill_Status/bills_text.cfm?billdoc=hb2962%20intr.htm&yr=2023&sesstype=RS&i=2962. |

| 64. | H.B. 19-1149, 2019 Regular Session (Colorado 2019) (enacted). https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb19-1149. |

| 65. | H.B. 21-1209, 2021 Regular Session (Colorado 2021) (enacted). https://leg.colorado.gov/bills/hb21-1209. |

| 66. | International law scholars Dirk van Zyl Smit and Catherine Appleton have compiled a comprehensive review of life imprisonment laws and figures in over 200 countries. Their exhaustive work represents the best of what is known regarding the practice of life sentences and is a useful resource for comparison to the U.S.’s overblown reliance on this punishment. The U.S. stands alone internationally in its widespread use of life with parole and life-without-parole for persons regardless of age and holds an estimated 40% of the world’s life-sentenced population, including 83% of those serving LWOP. |

| 67. | Van Syl Smit, D., & Appleton, C. (2019). Life imprisonment: A global human rights analysis. Harvard University Press. |

| 68. | Van Zyl Smit, D., & Appleton, C. (2019), see note 68. |

| 69. | Atwell, B. L. (2015). Rethinking the childhood-adult divide: Meeting the mental health needs of emerging adults. Albany Law Journal of Science and Technology, 25(1), 20.; Gur, R. C. (2021). Development of brain behavior integration systems related to criminal culpability from childhood to young adulthood: Does it stop at 18 years? Journal of Pediatric Neuropsychology, 7, 55-65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40817-021-00101-1. |

| 70. | The death penalty is equally if not crueler for these same reasons, but discussion of this penalty and its relation to LWOP goes beyond the scope of this report. |

| 71. | Solem v. Helm 463 U.S. 277 (1983). |

| 72. | Hannan, K. R., et al. (2023), see note 4. |

| 73. | National census of people serving life sentences are collected by The Sentencing Project. Most recent data are available at: Nellis, A. (2021), see note 8. |