From Punishment to Prevention: A Better Approach to Addressing Youth Gun Possession

Justice system responses to youth referred to court on weapons charges have grown increasingly punitive, with fewer youth diverted from prosecution and more youth placed in locked detention. Proven solutions exist that better support youth and improve community safety.

Related to: Youth Justice, Racial Justice

Executive Summary

Reducing gun violence should be an urgent priority in the United States. However, imposing harsh consequences for all adolescent gun possession cases harms urban youth of color disproportionately without benefits for community safety. Other approaches to reducing gun violence are far more equitable and effective.

Surveys find that roughly 5% of youth in the United States ages 12 to 17 – more than a million young people – carry a firearm each year.1 This high rate of gun possession is not new. Despite a significant uptick in gun sales during the pandemic, the share of U.S. youth who carry guns has held steady in recent years.2

Yet, amid a wave of alarming news coverage about youth violence3 and a sizeable uptick in gun violence against youth since 2012,4 youth arrests5 and court referrals6 for weapons possession – cases in which carrying a weapon, not brandishing it or using it to commit other crimes, is the most serious charge facing a young person – have been rising sharply since the start of the pandemic. A disproportionate and growing share of these cases involve Black youth,7 even though rates at which youth carry guns do not vary widely by race.8 Justice system responses for youth referred to court on weapons possession charges have grown increasingly punitive over the past decade, especially for black youth.9

Taken together, these trends present a vexing challenge. The continuing high rate of gun possession among youth is troubling, because adolescents’ immaturity can lead to impulsive behavior and poor decision making. Also, higher rates of gun possession are associated with more gun violence in communities. Given these realities, it may seem like common sense to aggressively prosecute and punish youth who carry firearms. However, a careful look at the evidence points in the opposite direction.

Unlike gun possession, which is widespread in all areas of the country, actual gun violence is highly concentrated geographically,10 and it is committed primarily by a very narrow segment of the youth and young adult population.11 Most youth who carry weapons do not use them to threaten others or to commit crimes. Rather than keeping us safer, aggressive law enforcement and inflexible and punitive court responses to youth gun possession are likely to worsen gun violence and other crime by youth. Meanwhile, inflexible punitive responses to adolescent gun possession damage young people’s futures, and they exacerbate the justice system’s already glaring racial disparities.

The most promising approaches to reduce gun violence involve comprehensive initiatives in which courts work with community partners to address the reasons why youth and young adults obtain guns, and whole communities mobilize to engage and intervene with youth and young adults who are at maximum risk for gun violence.12

Which Youth Carry Guns and Why?

Youth who carry firearms vary widely in their risks to commit gun violence. Many who are not involved in serious delinquency carry firearms for defensive purposes, because it’s common among their peers, or because they feel an extra need for self-protection tied to experiences of trauma. Another large cohort of youth who carry firearms are involved in delinquency but do not use their weapons to threaten others or commit crimes. A very small group of youth are engaged in serious criminal activity and are at extreme risk for gun violence.13

Gun violence amongst teenagers is a major problem and has led to many tragic incidents. [My county] does not have any formal programming that specifically addresses rehabilitation for juvenile gun offenders. Kids accused of gun possession are placed on a GPS; if they do well, then they stay in the community, and if they do poorly, then they go to placement. Some kids go on to reoffend because they live in neighborhoods where they do not feel safe walking around unarmed. None of our systems are addressing this issue.

Current Justice System Responses to Youth Gun Possession Are Highly Punitive – and Have Been Getting More So

For this report, The Sentencing Project conducted a national survey of public defenders and other youth justice system professionals, reviewed national data trends on youth arrests and weapons possession cases, and examined state and local court practices for handling youth gun possession cases. Specifically, we focused on cases where gun possession was the most serious charge, meaning that the young person did not fire their weapon, use it to commit a carjacking or other robbery, or brandish their weapon or use it to threaten others. The evidence shows:

- Inflexible and punitive responses to youth gun possession are commonplace. In our national survey, which resulted in 74 completed responses from 34 states and the District of Columbia, more than half the respondents (57%) characterized the courts’ handling of gun possession cases in their jurisdictions as “a major concern.”

- The share of gun possession cases resulting in diversion, where alleged misconduct is addressed outside of the formal justice system, has fallen nationally in recent years, while the use of detention has increased.14 In many state and local justice systems, youth arrested on gun possession charges are being categorically denied opportunities for diversion.

- In many jurisdictions, all youth arrested on gun charges – even in cases when they are arrested only for possession, not for threatening others with their weapons or using them as part of any other offense – are being placed in locked detention facilities.

- In many jurisdictions, it is common for youth to be transferred to adult court for gun possession charges.

- Few jurisdictions offer constructive interventions for youth accused of gun possession.

Punitive Responses to Youth Gun Possession Are Counterproductive and Inequitable

Given the varied reasons why youth carry firearms and the vastly different risks posed by different categories of youth, a one-size-fits-all approach to gun possession cases is ineffective and harmful. For most youth arrested on gun possession charges, research makes clear that punitive responses are counterproductive:

- Transfers to adult court lead to worse recidivism outcomes than retaining youth in juvenile court, and transfers are especially unwarranted for youth with little or no prior involvement in delinquency.15

- Placing youth in locked detention centers pending their court dates leads to worse public safety and youth development outcomes, and they should be used only for youth who pose a substantial risk to public safety.16

- Diversion tends to yield much better outcomes than formal court processing, especially (but not only) for youth with minimal involvement in delinquency and less risk to reoffend.17

- Aggressive policing of gun possession and inflexible prosecution of gun possession cases exacerbates racial disparities in the justice system.

- Aggressive policing and inflexible prosecution in gun cases also harm police-community relations and undermine young people’s trust in police and respect for the justice system.18

Recommendations: How Youth Justice Systems Can Better Handle Youth Gun Possession Cases and Work With Communities to Address Gun Violence

To limit the number of young people who carry firearms and especially to reduce youth gun violence, several practices show far greater promise than punitive and inflexible responses to gun possession in the justice system.

- Make diversion an option in gun possession cases rather than mandating formal prosecution for all cases, particularly when youth have no prior records.

- Where possible, develop targeted diversion programs specifically for youth facing gun possession charges. Such programs can be highly effective, but detention remain scarce.19

- Substantially narrow the use of detention for youth accused of gun possession and stop transferring youth to adult court for gun possession. Transfers should never be authorized, and detention should only be used in cases where youth arrested on gun charges pose a significant risk to commit serious new offenses or to abscond.

In addition, the courts should embrace comprehensive approaches to gun violence that mobilize whole communities to engage and support youth and young adults at highest risk.20

- Undertake effective community violence interruption efforts in areas where gun violence is widespread. America’s gun violence problem is highly concentrated geographically,21 and it typically involves only a small number of individuals even within high crime neighborhoods.22 Strategic partnerships between law enforcement and community organizations to reduce gun violence have shown marked success in many cities.23 In 2022, the federal budget allocated $300 million in grants to support these efforts; however, in April 2025 the Trump Administration terminated many of the funded programs, rescinding more than $150 million in much needed funding.24

- Invest in state-of-the-art cognitive behavioral interventions for youth at high risk for gun violence. Programs that help youth improve thinking and judgment skills have substantially lowered violence among youth at high risk.25

- Adopt and enforce common sense rules to limit young people’s access to firearms, including reasonable gun control laws and strong rules requiring the safe storage of firearms.

Part 1: Why worry about the justice system’s response to youth gun possession?

The time has come for justice systems across the country to re-examine their approach to youth gun possession.

This challenge is urgent because gun possession among America’s youth remains widespread and worrisome. Although the share of youth carrying weapons does not appear to have increased in recent years,26 the number of youth arrested on gun possession charges has risen significantly, and weapons possession represents a growing share of cases entering our nation’s juvenile courts. Also, court responses to youth gun possession are inextricably linked to the nation’s challenge to reduce gun violence, which has harmed increasing numbers of children and adolescents over the past dozen years.27

Part One of the report explains in more detail why the challenges around youth gun possession are urgent and timely. Subsequent sections of the paper address five key questions:

- Which youth are carrying firearms, and why?

- How do youth justice systems in the U.S.currently handle gun possession cases?

- Why is punitive and inflexible treatment of youth gun possession cases – the current norm in justice systems nationwide – counterproductive?

- How can youth justice systems better address youth gun possession cases?

- What other promising strategies can communities employ to minimize youth gun possession?

Youth Gun Possession Is a Serious Issue

Youth gun possession is widespread. Gun possession has been common among U.S. youth for decades. Two surveys, the Youth Risk Behavior Survey (YRBS) and the National Survey on Drug Use and Health (NSDUH), both show that youth gun possession is widespread among white, Black, and Latino youth.28 NSDUH finds 5% of youth ages 12 to 17 report carrying a handgun in the past year.29 In a nation with 26 million youth in this age group,30 that translates to more than one million youth carrying firearms. The two surveys offer conflicting answers on whether the share of U.S. youth carrying firearms is increasing: NSDUH shows a rise in youth gun possession since 2021 (after declining from 2017 to 2021), while YRBS shows a decline since 2017).31

Youth gun possession is dangerous. This high rate of gun possession among youth is worrisome for several reasons.

- Studies consistently find that high rates of gun possession contribute to gun violence.32 At the state level, high rates of gun possession are tightly correlated with high rates of youth gun violence. Also, communities where gun possession is common suffer far higher rates of overall violence than socioeconomically comparable communities with lower rates of gun possession.33

- Easier access to firearms in the U.S. has led to dramatically higher gun fatalities among youth when compared to other advanced democracies.34 For instance, one recent study found that the U.S. firearm death rate among children and adolescents was 37 times the average among 12 other high-income countries.35 American youth firearm deaths by suicide and unintentional injuries also far exceed those in other nations.36

- Adolescent behavior and brain development research underscore the urgency to minimize adolescents’ access to firearms. Youth who carry firearms are much more likely than other youth both to be victimized by and to commit gun violence.37 Because their brains are still developing, teens are less able than adults to exercise good decision-making, weigh the consequences of their actions, resist peer pressure, and avoid risky behaviors.38

Youth Arrests and Juvenile Court Cases Are Increasing, With Growing Disparities

Weapons possession39 represents an increasing share of cases in youth justice systems nationwide. The increase has been especially large for Black youth.

A recent rise in weapons possession arrests. In 1995, more than 43,000 young people were arrested for illegally carrying or possessing weapons. By 2019, fewer than 12,000 youth were arrested on weapons charges – down nearly three-fourths. However, youth weapons arrests have risen rapidly since the end of the pandemic. In 2023, more than 17,000 youth were arrested on weapons charges.40

More weapons cases in juvenile court. Paralleling the drop in arrests, the number of youth referred to juvenile delinquency courts on weapons charges nationally declined every single year from 2006 to 2020, falling from over 43,000 to 12,200.41 However, weapons possession referrals rebounded up to 19,000 in 2022.42

State and local data also point toward increases in youth weapons possession cases. In Florida, gun possession arrests increased by 45% between fiscal years 2018-19 and 2022-23, even as all other arrests fell by 19%.43 In Texas, court referrals involving firearms grew by 51% between 2018 and 2023 while all other referrals fell.44 Likewise Maryland,45 South Carolina,46 and Hamilton County (Cincinnati), Ohio47 have also seen substantial increases in weapons arrests for teens in recent years.

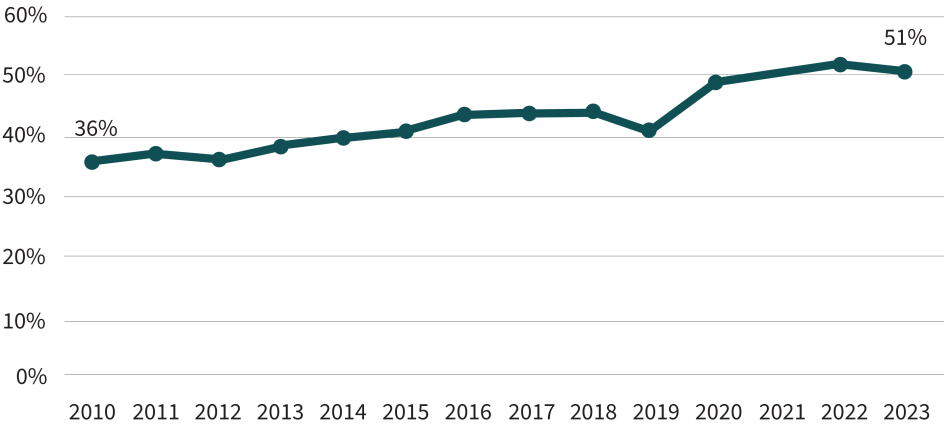

Increasing racial disparities in weapons possession cases. Black youth’s share of weapons possession arrests has grown from 36% in 2010 to 51% in 2023 (Figure 1). Similarly, racial disparities in weapons possession cases in juvenile courts have also increased markedly: after hovering at or below 40% from 2014 to 2019, the share of weapons cases involving Black youth rose to 49% in 2021.48

Figure 1: Black Youth Share of U.S. Juvenile Weapons Arrests

Source: FBI Uniform Crime Reports (2010-2023)

We have a major issue with individuals leaving firearms in unlocked vehicles and unsecured. Instead of penalizing adults who are irresponsible gun owners, the State of Florida has decided to harshly punish juveniles in possession of firearms. Almost every single gun offense no matter whether or not this is the juvenile's first time touching the delinquency system is being direct-filed to adult court. Fourteen- and fifteen-year olds with no history and first-time offenses are being direct-filed to adult court.

Gun Violence Has Been Claiming More Young Victims in Recent Years

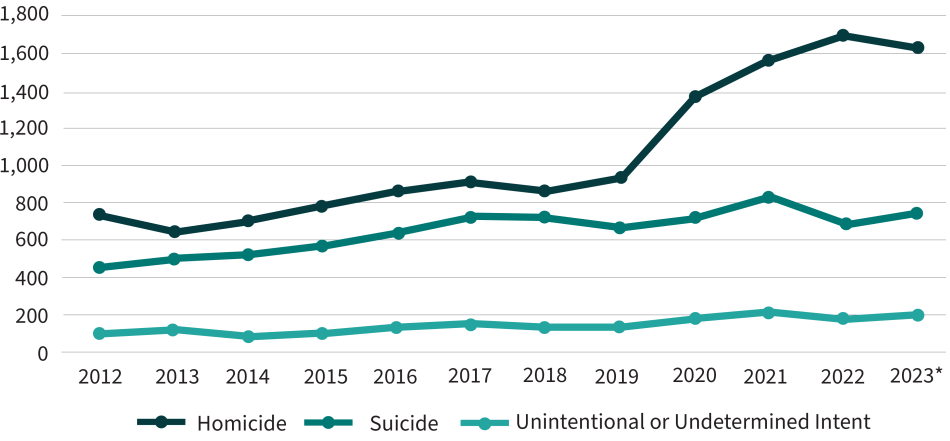

Gun violence causes substantial and increasing harm to America’s youth, especially youth of color. Gunshot wounds recently overtook car accidents as the number one cause of death for U.S. children and adolescents.49 In 2022, gunshots took the lives of 2,526 young people50 – nearly twice as many as in 2012.51 The vast majority (90%) involved children ages 10 to 17.52 An increasing share of youth firearm deaths nationwide result from gun assaults, rather than suicides or accidents (Figure 2).53

Figure 2: Firearm Deaths in the U.S. Among Children Under 18, By Cause

* Data for 2023 are provisional.

Source: Data from 2012-2020 from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Mortality 1999-2020 on CDC WONDER Online Database, released In 2021. Data from 2021-2023 from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics. National Vital Statistics System, Provisional Mortality on CDC WONDER Online Database. Data are from the final Multiple Cause of Death Files, 2018-2022, and from provisional data for years 2023-2024.

Non-fatal gunshot injuries have also been rising,54 and they cause substantial and growing harm to the physical and mental health of U.S. youth.55 Gun violence also creates indirect harm56 through the trauma experienced by millions of U.S. children and youth who see or hear gunshots in their communities each year57 or have a friend or family member murdered.58 Youth exposed to gun violence in childhood are significantly more likely to carry firearms59 and to commit acts of violence than comparable youth who are not exposed.60

The harms from gun violence afflict youth of color disproportionately, and they are heavily concentrated among youth living in neighborhoods with high poverty levels. Nationwide, nearly half (48%) of all youth killed by firearm violence in 2022 were Black.61 More than half of all gun homicides from 2020 to mid-2024 occurred in neighborhoods that are home to only 6% of the U.S. population – primarily urban neighborhoods with concentrated poverty populated predominantly by people of color.62 Youth of color are also far more likely than their white peers to witness gun violence.63

Addressing these disturbing trends in youth gun violence presents an urgent health and public safety priority. Ensuring that the courts handle youth gun possession cases effectively must be part of the solution.

Part 2: Which youth carry firearms and why?

Crafting effective responses to youth gun possession is possible only after considering the characteristics of youth who carry firearms, their reasons for doing so, and their relative risk to commit gun violence.

Youth gun possession is common among many demographic groups. Though Black youth, and to a lesser extent Latino youth, are far more likely than white youth to be gunshot victims, gun possession is not concentrated heavily among youth living in central city urban neighborhoods, and rates of gun carrying do not vary dramatically by race, ethnicity, or geography. The most recent National Survey on Drug Use and Health (in 2023) showed that carrying a handgun was more prevalent among white youth than Black youth, and equal between Non-Hispanic white youth and Latino youth.64 Youth in rural and smaller metro areas were also more likely to carry handguns than youth in larger metro areas.65 Likewise, in the most recent Youth Behavior Risk Survey (2023), Black high school students were no more likely to carry guns than their white peers.66

Only a small fraction of youth who carry guns use them to commit violent crimes. Whereas survey data indicate that more than a million youth carry firearms each year,67 these youth commit fewer than 8,000 serious gun crimes each year, according to a report published by the nonpartisan Council on Criminal Justice in 2024 citing data from the National Incident-Based Reporting System.68

Many youth acquire guns for self-defense or as a consequence of fear and trauma, not to threaten or victimize others. Surveys that ask young people whether and why they carry weapons show that, in most cases, youth gun possession is motivated by a desire for self-defense rather than an intent to commit violent crimes or engage in delinquent conduct. For instance, a majority of the 13 studies reviewed by Oliphant and colleagues in 2019 found that young people’s primary motive to carry firearms was “a perceived need for protection/self-defense.”69

Trauma and victimization: Many youth who carry weapons are themselves victims, and youth gun possession is linked to a variety of family and community factors beyond their control. Youth who have been exposed to trauma as children – such as experiencing physical abuse, having a family member incarcerated, or having a family member with a substance abuse problem – are far more likely to carry firearms as adolescents.70 Exposure to multiple types of traumatic experiences is especially predictive of gun possession in adolescence.71 Being bullied or victimized by other youth also increases young people’s likelihood to possess firearms.72

Exposure to violence: Youth gun possession arrests are higher in neighborhoods beset by crime and violence where residents lack faith in police and the justice system to protect them.73 Many youth who carry weapons have been victims of violent crime or have had family members victimized.74

The role of delinquent peers: Youth who associate with delinquent peers, and those who are involved in the delinquency court system or connected to gangs, are more likely to carry firearms than their peers. But even these youth report that the choice to carry weapons – or to affiliate with a gang – is motivated most often by a desire for self-protection.75 These youth often report that, due to lack of opportunity in the mainstream economy, they are forced to participate in the underground economy and don’t trust the police to protect them.76

Youth who carry firearms vary widely in their reasons and risks for involvement in gun crimes. Youth who carry weapons typically fall into one of three categories:

- One large group includes youth who are not involved in serious delinquency but carry firearms for defensive purposes, because it’s common among their peers, or because they feel an extra need for self-protection rooted in experiences of trauma. These youth typically pose little risk for committing gun violence. “Not all adolescents carry guns for use in illegal activity,” wrote criminologist Lacey Wallace. “[T]here are many adolescents who own weapons and never carry them to school or use them for illicit purposes.”77

- Another large group of youth are involved in some degree of delinquency, or they associate with peers who are involved in delinquency,78 but they do not use their weapons to threaten others or commit crimes.

- Finally, a very small group – less than 1% – are engaged in serious criminal activity and are at extreme risk for gun violence.79 As one recent report concluded, “Analyses in a variety of cities have found that small networks of individuals – sometimes as little as a couple hundred in a city of millions – are involved in most of the city’s shootings.”80

The circumstances faced by these three categories of youth differ substantially, and their likelihoods to commit gun violence are vastly unequal. Therefore, it is senseless for justice systems to treat all gun possession cases the same.

Many youth are being held in detention for simple CCW [carrying a concealed weapon] or Improperly Handling a Firearm in a Vehicle. Many counties have automatic holds for youth with any [gun] offense. The dangers of detention for what now is essentially a status offense (Ohio has passed much more lax gun laws recently) runs counter to [the Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention Act] and decades worth of research about the dangers of detention.

Part 3: Youth Justice Systems’ Treatment of Gun Possession Cases is Punitive – And Has Gotten More So

To gather data about youth justice systems’ handling of cases of youth arrested for gun possession, The Sentencing Project partnered with the Gault Center, formerly the National Juvenile Defender Center, to conduct a survey of public defenders and other youth justice system professionals across the country.81 We received completed survey forms from 74 respondents in 34 states and the District of Columbia. More than half (57%) reported that they see the courts’ handling of gun possession cases in their state as “a major concern.” Another 26% of respondents deemed the state’s handling of gun possession cases as a “moderate concern.”

The survey also asked about state and local policies and practices regarding opportunities for diversion or informal processing of gun possession cases, the use of detention for gun possession cases, and transfers of youth to adult courts in gun possession cases. The survey responses predominantly expressed dissatisfaction: Most respondents (70%) indicated that they do not know of any positive or effective state or local policies or practices for handling youth gun possession cases. Just 22% answered that they are aware of any constructive approaches. By contrast, 70% reported being aware of harmful or counterproductive policies and practices in their jurisdiction for addressing youth gun possession cases.

In addition to analyzing this survey data, The Sentencing Project reviewed national data on youth weapons arrests and court cases and examined state and local approaches to handling youth gun possession cases. This inquiry yielded several findings.

Punitive Responses to Youth Gun Possession Are Common in Many State and Local Justice Systems

Many states and many local justice systems treat youth who are referred to courts on gun possession charges harshly, even when these youth have no prior history of delinquency or gun possession, do not score as high risk to offend, and have not threatened anyone with their weapons or used their weapons in a crime.

Few youth arrested on gun possession charges are diverted from court. Diversion, where alleged misconduct is addressed outside of the formal justice system, is a common practice in youth justice and has been for decades. Nationwide, just under half of all cases referred to juvenile courts on delinquency cases are handled informally.82 Also, an increasingly compelling body of research shows that diversion from court leads to far more favorable outcomes, including lower likelihood of future justice system involvement and better success in school and employment.83 Yet several survey respondents who commented about the availability of diversion opportunities stated that, due either to state laws or local court customs, youth referred to court on firearm possession charges were routinely denied diversion opportunities.

Just two survey respondents identified active programs or practices offering diversion for youth charged with gun possession. One, in New Mexico, noted that the state has only one gun diversion program, and it has a months-long waiting list. The other, in Massachusetts, explained that “only one of our 14 county District Attorneys has been known to divert simple gun possession cases, and even that is a rarity.”

| Arizona | “The state used to offer diversion for first time offenders, now all youth are petitioned into court.” |

| Connecticut | Gun possession charges against youth are considered “serious juvenile offenses” and are ineligible for informal processing outside of court.* |

| Michigan | While there is no statewide rule or statute, “It is commonly understood that there will be a formal petition” in all gun cases. |

| South Carolina | “Our prosecutors refuse to divert any gun charges.” |

| Utah | “State law now requires diversion for youth accused of most misdemeanors;** however, diversion is specifically prohibited for youth charged with a misdemeanor gun possession charge.”*** |

* Callahan, J. (2021). Juvenile Delinquency Procedure. Connecticut Office of Legislative Research.

** Utah Code Section 80-6-303.5.

*** Utah Code Section 76-10-505.

In most jurisdictions, virtually all youth arrested on gun charges, even possession, are placed in locked detention cells. Of the 48 survey respondents who provided information on the use of detention for gun possession cases, 44 (92%) said that detention is imposed in all or the vast majority of cases. Some of these respondents said that the use of detention was required under a detention assessment instrument, others noted that detention was mandated by a state law or a formal rule or policy, and the largest share said that detention was typically ordered as a matter of custom by prosecutors, judges or probation personnel. A defender in South Carolina reported that “Offenses involving weapon possession result in de facto automatic detention, which has contributed to the overcrowding and dangerous conditions at our state detention facility. Gun detentions and commitments disproportionately affect minority youth.” A survey respondent in Connecticut reported that “When a gun is involved, however minimal (mere possession in car or on person), youth are detained regardless of assessed level of risk to the public.”

In September 2023, New Mexico’s governor signed an order mandating detention for all youth arrested for any offense involving a firearm.84 In the first three months after the order went into effect, nearly one third of the youth detained statewide would previously have been allowed to remain at home pending their court dates.85

Some youth face felony charges for gun possession in juvenile court even if they have not threatened anyone with their weapons or used them for delinquent purposes. Twelve survey respondents expressed concern that many youth in their jurisdictions are facing felony charges for gun possession even in situations where they did not wield or threaten anyone with their weapon or use it in the commission of other offenses. In Utah, under a 2024 law change, handgun possession by youth is now a felony.86 In Florida, as of 2024, first-time gun possession charges for youth remain a misdemeanor; however, subsequent offenses are now classified as felonies.87 Likewise in Georgia, a second gun possession offense for minors is considered a “designated felony act” that requires a 36-month commitment to state custody, including up to 18 months of restrictive confinement in a state youth correctional facility.88

Many youth are transferred to adult court for gun possession. In New York, for instance, 16- or 17 year-olds accused of weapons possession are automatically charged as if they were adults. So are the vast majority of 13- to 15-year-olds arrested for gun possession in New York City (and many youth in other parts of the state) due to rules mandating transfers for possessing weapons within 1,000 feet of a school.89 In Maryland, state laws require that weapons possession cases for 16- and 17-year-olds originate in adult court. These cases are typically waived back to juvenile court90 after youth spend months in locked detention.91 In Indiana, charges against youth over 15 for carrying a handgun are automatically waived to adult court.92 In Illinois, youth 15 and older are excluded from juvenile court (and automatically charged as adults) if charged with “Aggravated Unlawful Use of a Weapon,” which under state law includes any unlawful possession of a firearm.93

Few jurisdictions offer constructive programming for youth accused of gun possession. The Sentencing Project’s scan of policies and practices for handling youth gun possession cases revealed very few examples of state or local programs designed to intervene positively in the lives of youth caught with firearms. None of the survey respondents identified intervention programs in their jurisdictions to address the reasons behind youths’ decisions to obtain and carry weapons or to help youth avoid impulsive decisions if they do carry weapons.

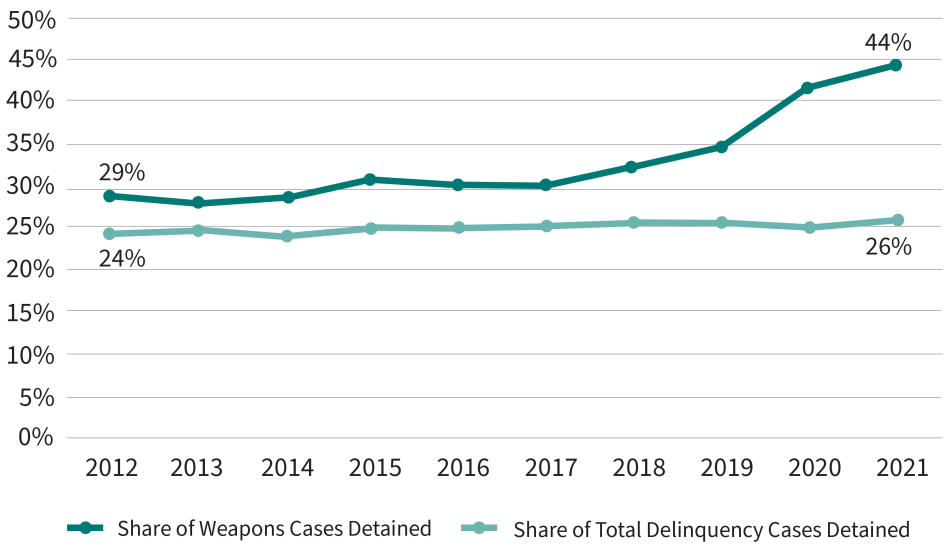

The Justice System’s Response to Gun Possession Has Been Getting Even More Punitive

National data show that youth justice systems grew more punitive towards youth referred to court on weapons possession charges in the years before the pandemic. Formal court processing (instead of diversion) grew from 57% of weapons cases in 2005 to 67% in 2021, the last year for which data are available. From 2012 to 2021, juvenile courts also increased the share of weapons cases in which youth were placed into detention from 28% to 44%, while the likelihood of detention for other offenses remained flat (Figure 3).94

Figure 3. Share of Youth Detained (2012-2021): Weapons Cases vs. Total Delinquency Cases

Source: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice.

Part 4: The Justice System’s Punitive Approach to Youth Gun Possession is Counterproductive and Inequitable

The available evidence makes clear that inflexible and punitive responses to youth gun possession in court are ineffective policy as well as racially unjust. Specifically, the research makes clear that:

- Transfers to adult court lead to worse outcomes. Decades of research show that trying youth in adult courts and punishing them in adult corrections systems does not reduce reoffending behavior.95 However, transfers to adult court leave youth with a criminal record that will limit their opportunities for a lifetime. Transfers deny youth access to the age-appropriate education and mental health programming resources available in the juvenile justice system. Transfers are especially unjustified for youth charged with gun possession.

- Placing youth in locked detention centers pending their court dates is often counterproductive and unnecessary. Measured against comparable youth who are allowed to remain at home pending their court dates, youth who are detained have three times the likelihood of placement into correctional institutions for the initial offense, higher likelihood of returning to court on subsequent charges, and far greater chance of dropping out before completing high school.96 Locked detention should therefore be imposed only for youth whose weapons possession poses significant risk to public safety.

- Diversion tends to yield much better outcomes than formal court processing, especially for youth with minimal involvement in delinquency. Research shows that, compared with comparable youth who have engaged in similar misconduct but are not prosecuted in court, youth who enter the court system are more likely to reoffend, and they are far less likely to succeed over time in school or employment.97 Involvement in the justice system has been especially counterproductive for youth with little or no prior involvement in delinquency and low risk to reoffend.98

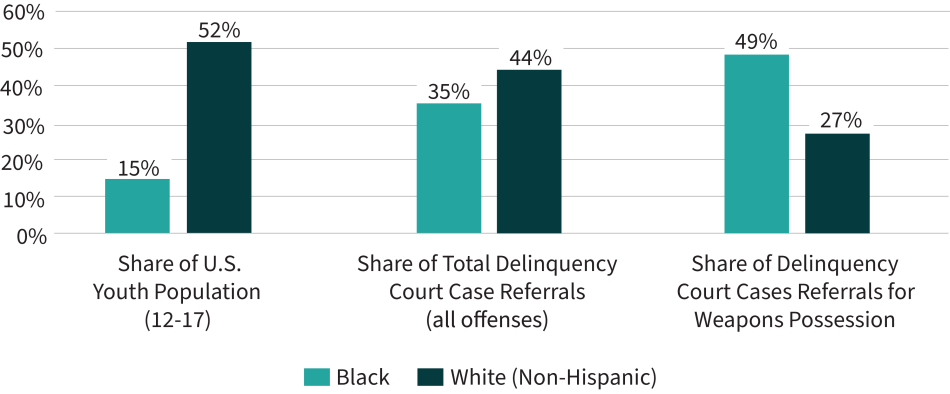

- Aggressive policing and inflexible prosecution of youth gun possession exacerbates disparities. Rates of gun possession among Black and white youth are similar nationwide.99 Yet even though Black youth represented just 15% of the nation’s youth population, juvenile court data show that nearly half (49%) of all youth referred to juvenile courts on weapons charges in 2021 were Black.100 White youth, who make up 52% of the youth population, were involved in just 27% of delinquency court weapons cases.101 While it’s true that Black youth are far more likely to be killed by gun violence, that by no means justifies glaring disparities in arrests and court referrals for gun possession. Among all demographic groups, the vast majority of youth who choose to carry firearms are not involved in gun violence, and the evidence makes clear that punitive responses for gun possession do nothing to protect the public.

- Aggressive policing and inflexible prosecution of gun possession offenses harms police-community relations and reduces the effectiveness of the justice system. “Typical police tactics meant to confiscate firearms and decrease violence, such as high levels of pretextual vehicle stops or pedestrian stop and frisks, have not been shown to reduce gun violence,” one recent study found. “Such tactics instead work to alienate communities, as these actions feel invasive and focused on the wrong people. The resulting lack of trust perpetuates unwillingness to cooperate and share information, making it even more difficult to solve shootings in many of these communities.”102

Figure 4. Race Disparities in Youth Gun Possession Cases (2021)

Sources: Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2024). “Easy Access to Juvenile Populations: 1990-2022.” National Center for Juvenile Justice; Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). “Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021.” National Center for Juvenile Justice.

The majority of my cases charged in adult court, and especially those remaining in the adult court system, are firearm cases. All the youth charged are Black and Latinx and most of the time the police don't have a good reason to stop them… Probation won't offer informal adjustment [diversion] on [gun] cases.

Part 5: How youth justice systems can better handle youth gun possession cases

To limit the number of young people who carry weapons and reduce the harms that result from youth access to firearms, several court practices show far greater promise than inflexible and punitive responses that currently predominate in youth justice systems nationwide.

Recommendation: Allow diversion as an option in gun possession cases.

Diversion from the justice system improves young people’s likelihood of succeeding in school and avoiding future involvement in the justice system.103 It therefore makes little sense for justice systems to continue mandating formal prosecution of all youth caught in possession of a firearm. Rather, diversion should be the presumption for youth with no delinquency history facing first time gun possession charges, and diversion should be considered for other youth facing gun possession charges.

Recommendation: Where possible, develop tailored diversion programs to work with youth facing gun possession charges.

In addition to allowing the cases of youth accused of gun possession to be handled informally, youth justice systems should develop targeted diversion programs specifically for youth who carry guns.

Diversion programs specifically targeted to youth accused of gun possession are scarce. The Sentencing Project has identified such programs operating in only a handful of jurisdictions nationwide, including Chatham County (Savannah), Georgia,104 Clayton County, Georgia,105 Denver, Colorado,106 Miami-Dade,107 Florida, New York City,108 and Tampa, Florida.109 However, diversion programs can be more effective for many youth apprehended with guns than standard approaches involving pre-trial detention, punitive prosecution, and GPS monitoring or incarceration. Likewise, studies in the adult justice system also find that diversion programs for gun possession yield promising results.110 (See section below on Gun Diversion Programs for Youth)

Over the past two years there has been a rapid increase in the number of possession/disorderly-conduct-with-a-weapon cases. The state used to offer diversion for first time offenders, now all youth are petitioned into court… Also alarming, is the court and probation has taken a harsher stance with these youth.

Recommendation: End mandatory detention for youth accused of gun possession and transfer of youth to adult court for gun possession.

Stop compulsory detention for all gun possession cases. Detention should only be used in cases where youth pose a significant risk to commit serious new offenses or to flee rather than appear for their scheduled court dates. When courts use objective screening tools to guide detention decisions, gun possession should be considered a significant risk factor, but it should not be weighted so heavily that detention becomes a forgone conclusion whenever a youth is found in possession of a firearm.

Stop transferring youth to adult court based on gun possession charges. State and local justice systems should end the practice of transferring youth to adult court; however, transfers are especially problematic for youth who are accused only of weapons possession and have not used a weapon to threaten others or commit a more serious offense.

Gun Diversion Programs for Youth

In Tampa, an organization called Safe and Sound Hillsborough has been offering a diversion program since 2022 for youth charged with weapons possession.111 Over the course of six months, program participants visit a trauma center, emergency room, and a morgue. They meet with people affected by gun violence as well as individuals formerly incarcerated for gun violence. Youth take part in evidence-based cognitive behavioral therapy groups where they learn anger management, perspective-taking, and other skills critical for mature decision making. The youth are also assigned mentors and receive academic support. Among 204 youth who had completed the program by December 2024, 168 (82%) had avoided a new charge for one year (if discharged by December 2023) or for a shorter period (if discharged more recently).112

In Denver the district attorney’s office created the Handgun Intervention Program in 2021 for youth referred to court on gun possession charges. Participating youth attend weekly meetings for seven weeks, as well as bi-weekly court hearings. Youth receive training on cognitive behavioral skills, listen to the stories of gun violence survivors, and meet and engage with police officers. In their final group session, participants deliver presentations describing what they have learned in the program and stating their goals for the future.113 As of December 2024, the program had served about 60 youth in ten cohorts. An outcome evaluation of the program is underway. Preliminary data show that, as of December 2024, 90% of youth in the first eight cohorts had been successful in avoiding a new charge in delinquency court.114

Part 6: Promising strategies to minimize youth gun possession and to reduce youth and young adult gun violence

Increasingly, public health experts agree that the most effective strategies to reduce gun violence among both youth and young adults are not found in law enforcement and court prosecution. Rather, the most promising strategies seek to identify and address the reasons why youth and young adults obtain guns and become involved in gun crimes,115 and to intervene strategically with the limited population of young people at greatest risk for gun violence.

“[Because] the majority of violent crime in any given city is committed by a very small percentage of high-risk individuals, a more strategic approach to gun-related cases is needed,” concluded a recent report by the Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence, “one that includes as many off ramps as possible for individuals who do not actually pose a threat to their communities.”116 These off-ramps are especially important for youth.

Recommendation: Develop, fund and support effective community violence interruption efforts in areas where gun violence is widespread.

America’s gun violence problem is highly concentrated geographically,117 and even within high crime neighborhoods only a small number of people – typical young men – comprise most of both the shooters and the victims.118

Violence interruption initiatives aim to break the cycle of violence in these neighborhoods, Typically, these efforts involve partnerships between law enforcement and community organizations, which often employ social workers as well as “credible messengers” – individuals with experience in the justice system, many of them formerly incarcerated – who work directly with young men at highest risk for gun crimes.

These initiatives have a proven track record in reducing gun violence. For instance, violence interruption initiatives have been credited with reducing youth homicides by 63% in Boston; lowering group (or gang-member) homicides by 32% in New Orleans and 41% in Cincinnati; decreasing gun violence injuries by 50% and 37% in the East New York and South Bronx sections of New York City;119 and reducing average monthly shootings by 73% in New Haven, Connecticut.120 In Sacramento, California, the Advance Peace violence interruption program targeted 50 youth and young adults at high risk for perpetrating gun violence.121 Participants received daily support from a credible messenger mentor, developed life plans, earned $1,000/month stipends, and received other support such as cognitive-behavioral therapy, anger management, and substance abuse treatment. At the end of the 18-month program, 90% had no new gun charges; further, gun violence dropped 18% citywide, and 29% in one targeted neighborhood.122

Based on these promising results, the federal government established a Community-Based Violence Intervention and Prevention Initiative in 2022, allocating $300 million for violence intervention programming, training, evaluations, and related research.123 However, in April 2025, the U.S. Department of Justice announced the termination of 373 justice department grants, with total project costs of $820 million,124 including $153 million for violence intervention programs and related research.125 In a May 2025 report, the nonpartisan Council on Criminal Justice concluded that: “these funding cuts put public safety at risk and undermine hard-won reductions in violent crime.”126

Recommendation: Invest in state-of the-art cognitive behavioral interventions for youth at high risk for gun violence.

Adolescents are at heightened risk for delinquent conduct due to lack of emotional and psychological maturity: the parts of the brain that control judgement, perspective-taking, and impulse control do not develop fully until age 25.127

Cognitive-behavioral therapies that help young people accelerate the development of their thinking skills and improve their judgement are among the most effective strategies for reducing youth offending.128 Offering these interventions to youth at high risk offers a promising and important opportunity for reducing gun violence. In Baltimore and multiple sites in Massachusetts, Roca, Inc., has been offering individualized cognitive behavioral treatment along with mentoring and a variety of other supports to youth at high risk for gun violence, with very promising results.129 In Chicago, several programs offering cognitive behavioral therapies have proven highly effective in reducing young people’s likelihood of committing violent crimes.130 These models should be replicated or adapted in many other jurisdictions to reduce gun violence. The federal government should provide more funding for these efforts, rather than defunding them.

Recommendation: Adopt and enforce common-sense rules to limit young people’s access to firearms.

States and local jurisdictions should adopt reasonable gun control laws that reduce the availability of firearms that might fall into the hands of youth and rules requiring the safe storage of firearms to minimize young people’s access to weapons.

Studies find that gun control laws requiring universal background checks on gun sales, banning assault weapons, prohibiting gun sales to individuals at high risk for violence, or limiting gun carrying in public places lead to lower rates of gun violence, as well as less youth gun possession.131 For instance, two recent studies have found that youth gun possession is lower in states with stricter gun control regulations.132

Laws requiring safe storage of weapons – keeping firearms locked away unloaded, and stored separately from ammunition – have been shown to significantly reduce both homicides and suicides among young people.133 Also, multiple studies have found that when family physicians provide families with brief counseling on gun safety during routine pediatric check-ups, children’s access to firearms falls significantly.134

Conclusion

The evidence provided in this report shows that our nation’s youth justice systems are failing when it comes to youth gun possession. In many states and localities, youth justice systems are handling youth gun possession cases with inflexible punitiveness.

Clear and compelling evidence shows that involving youth in the justice system, locking them in detention facilities, and prosecuting them in adult courts all tend to increase their likelihood of reoffending and returning to the justice system. These approaches to gun possession exacerbate racial disparities and make communities less safe. Especially for those without any prior history in the justice system – they make youth less successful and more dangerous as well. Far better to divert many gun possession cases away from the justice system, to help youth build their maturity in decision making, and to address young people’s reasons for choosing to carry a weapon in the first place. In addition, the evidence is overwhelming that the most effective strategies to reduce youth gun violence involve intensive interventions for the very narrow segment of youth (and young adults) who are at maximum risk for gun violence.

My concern is punishing the juvenile where instead education and information could be more beneficial,” wrote a public defender in Minnesota. “I do not think kids realize/appreciate the true risk of carrying around guns. Just adding a felony on their record with probation does little to change that.

Appendix: Youth and Gun Possession Survey

For this report, The Sentencing Project prepared the following survey questionnaire about the handling of gun possession cases in the nation’s youth justice systems. In September 2024, Gault Center emailed the survey to the 108 members of its national advisory board and its nine regional advisory boards, and to the Gault Center’s larger mailing list of more than 1,000 youth defenders and other youth justice professionals nationwide.

| 1. | YRBS Explorer (Youth Risk Behavior Survey). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; and Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality. (2024). 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Public Use File Codebook, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States (1993-2023). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (See links here for 2017-2023 and for prior years in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report); and National Survey on Drug Use and Health. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. |

| 3. | Mendel, R. (2025). The Real Cost of ‘Bad News’: How Misinformation is Undermining Youth Justice Policy in Baltimore. The Sentencing Project. |

| 4. | Panchal, N. (2024). The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation; Villarreal, S., Kim, R., Wagner, E., Somayaji, N., Davis, A., & Crifasi, C. K. (2024). Gun violence in the United States 2022: Examining the burden among children and teens. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. |

| 5. | These data come from FBI Crime in the United States Reports, Table 38. Reports from 1995 to 2019 available at the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Report online archive, and reports from 2020 through 2023 available at the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Crime Data Explorer website. |

| 6. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 7. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy access to juvenile court statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice; Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A. and Kang, W. (2024). Easy Access to Juvenile Populations: 1990-2022. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 8. | 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health Public Use File Codebook, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. |

| 9. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 10. | Gebeloff, R., Lai, K.K. R., Murray, E., Williams, J. and Lieberman, R. (2024, May 14). How the pandemic reshaped American gun violence. New York Times. |

| 11. | Lurie, S. (2019, February 25). There’s no such thing as a dangerous neighborhood. Bloomberg. |

| 12. | Organizations supporting comprehensive approaches to youth gun violence include: American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Psychological Association; Johns Hopkins University Center for Gun Violence Solutions; Joyce Foundation; National Academy of Medicine; and the U.S. Surgeon General. |

| 13. | Center for Gun Violence Solutions (n.d.) In depth: Community Gun Violence (web page). Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University. |

| 14. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 15. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007). Effects on violence of laws and policies facilitating the transfer of youth from the juvenile to the adult justice system: A report on recommendations of the task force on community preventive services. MMWR 2007; 56 (No. RR-9). |

| 16. | Mendel, R. (2023). Why youth incarceration fails: An updated review of the evidence. The Sentencing Project. |

| 17. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A hidden key to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project. |

| 18. | Birckhead, T.R. (2009). Toward a theory of procedural justice for juveniles. Buffalo Law Review, 57(5). |

| 19. | Soe-Lin, H., Sarver, A., Kaufman, J., Sutherland, M., & Ginzburg, E. (2020). Miami-Dade County Juvenile Weapons Offenders Program (JWOP): a potential model to reduce firearm crime recidivism nationwide. Trauma surgery & acute care open, 5(1); Colombini, S. (2023, December 11). More kids are getting arrested with guns. A Tampa program aims to turn their lives around. WUSF Radio; interview with Freddie Barton, executive director, Safe and Sound Hillsborough, Tampa, FL, December 18, 2024; and interview with Deborah Garcia Sandoval, Probation Officer/ Handgun Intervention Program HIP-Coordinator, Denver County Juvenile Court Probation, December 11, 2024. |

| 20. | Organizations supporting comprehensive approaches to youth gun violence include: American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Psychological Association; Johns Hopkins University Center for Gun Violence Solutions; Joyce Foundation; National Academy of Medicine; and the U.S. Surgeon General. |

| 21. | Gebeloff, R., Lai, K.K. R., Murray, E., Williams, J. and Lieberman, R. (2024, May 14). How the pandemic reshaped American gun violence. New York Times. |

| 22. | Lurie, S. (2019, February 25). There’s no such thing as a dangerous neighborhood. Bloomberg. |

| 23. | Lau, C. (2024). Interrupting gun violence. Boston University Law Review., 104, 769. |

| 24. | Council on Criminal Justice (2025). DOJ Funding Update: A Deeper Look at the Cuts. |

| 25. | Mendel, R. (2023). Effective alternatives to youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project; and Building safer communities: Behavioral science innovations in youth violence prevention (2024). University of Chicago Crime Lab. |

| 26. | Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States (1993-2023). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

| 27. | Panchal, N. (2024). The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation. |

| 28. | Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States (1993-2023). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

| 29. | Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. |

| 30. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A. and Kang, W. (2024). Easy Access to Juvenile Populations: 1990-2022. U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention. |

| 31. | YRBS Explorer (Youth Risk Behavior Survey). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

| 32. | At the state level, Miller et al (2007) found that “for every 1% increase in household gun ownership youth homicides committed with guns increased by 2.4%.” Source: Miller, M., Hemenway, D., & Azrael, D. (2007). State-level homicide victimization rates in the U.S.in relation to survey measures of household firearm ownership, 2001–2003. Social science & medicine, 64(3), 656-664. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.09.024. |

| 33. | Moore, M. D., & Bergner, C. M. (2016). The relationship between firearm ownership and violent crime. Justice Policy Journal, 13(1). |

| 34. | McGough, M., Amin, K., Panchal, N. & Cox, C. (2023). Child and teen firearm mortality in the U.S. and peer countries. Kaiser Family Foundation. |

| 35. | Cunningham, R. M., Walton, M. A., & Carter, P. M. (2018). The major causes of death in children and adolescents in the United States. New England journal of medicine, 379(25), 2468-2475. DOI: 10.1056/NEJMsr1804754 |

| 36. | Grinshteyn, E., & Hemenway, D. (2019). Violent death rates in the U.S. compared to those of the other high-income countries, 2015. Preventive medicine, 123, 20-26. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.02.026. |

| 37. | Branas, C. C., Richmond, T. S., Culhane, D. P., Ten Have, T. R., & Wiebe, D. J. (2009). Investigating the link between gun possession and gun assault. American journal of public health, 99(11), 2034-2040. https://doi.org/10.2105/ajph.2008.143099; Webster, D. W., Meyers, J. S., & Buggs, M. S. (2014, February). Youth acquisition and carrying of firearms in the United States: Patterns, consequences, and strategies for prevention. In Proceedings of Means of violence workshop, forum of global violence prevention. Washington, DC: Institutes of Medicine of the National Academies. |

| 38. | Steinberg, L., Cauffman, E., Woolard, J., Graham, S., & Banich, M. (2009). Are adolescents less mature than adults?: Minors’ access to abortion, the juvenile death penalty, and the alleged APA” flip-flop.” American psychologist, 64(7), 583. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014763. |

| 39. | At a national level, data on gun possession cases is not available. The most relevant regularly reported information relates to weapons cases, which can include knives and other weapons in addition to firearms. |

| 40. | These data come from FBI Crime in the United States Reports, Table 38. Reports from 1995 to 2019 available at the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Uniform Crime Report online archive, and reports from 2020 through 2023 available at the Federal Bureau of Investigation’s Crime Data Explorer website. |

| 41. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice |

| 42. | Hockenbury, S. and Puzzanchera, C. (2024). Juvenile Court Statistics 2022. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 43. | Florida Department of Juvenile Justice (2024). Delinquency Profile Dashboard. |

| 44. | Texas Juvenile Justice Department (2024). Trends in Juvenile Justice and TJJD youth 2018-2023 (TJJD by the Numbers). |

| 45. | In Maryland, total referrals for gun possession – including cases processed in both juvenile and adult courts – hovered at around 500 per year from 2016 to 2019, then dipped below 400 in 2020. Since then, however, arrests have climbed steadily, reaching more than 1,000 in 2023. Source: Maryland Department of Juvenile Services (2016-2024). Data Resource Guide. |

| 46. | In South Carolina, juvenile court referrals for weapons offenses hovered in the range of 500-600 per year from Fiscal Year 2014/15 through Fiscal Year 2018/19. Since then, they have jumped significantly, with more than 1,000 referrals in each of the last three years. Source: email from Craig R. Wheatley, Director of Research and Statistics, South Carolina Department of Juvenile Justice (Nov. 12, 2024). |

| 47. | Hamilton County saw an increase in youth weapons possession arrests every year from 2019 to 2023, with the number of youth arrests for weapons possession rising from 59 to 137. Source: Hamilton County Juvenile Court (2010-2023). Annual Report. |

| 48. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention. |

| 49. | Panchal, N. (2024). The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation. |

| 50. | Villarreal, S., Kim, R., Wagner, E., Somayaji, N., Davis, A., & Crifasi, C. K. (2024). Gun Violence in the United States 2022: Examining the Burden Among Children and Teens. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. |

| 51. | Panchal, N. (2024). The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation. |

| 52. | Villarreal, S., Kim, R., Wagner, E., Somayaji, N., Davis, A., & Crifasi, C. K. (2024). Gun Violence in the United States 2022: Examining the Burden Among Children and Teens. Johns Hopkins Center for Gun Violence Solutions. Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health. |

| 53. | Panchal, N. (2024). The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation. |

| 54. | Panchal, N. (2024). The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation. |

| 55. | Song, Z., Zubizarreta, J. R., Giuriato, M., Koh, K. A., & Sacks, C. A. (2023). Firearm injuries In children and adolescents: Health and economic consequences among survivors and family members. Health affairs, 42(11), 1541–1550. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2023.00587. |

| 56. | Shulman, E.P. et al. (2021). Exposure to gun violence: Associations with anxiety, depressive symptoms, and aggression among male juvenile offenders. Journal of clinical child & adolescent psychology. https://doi.org/10.1080/15374416.2021.1888742; and Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., Turner, H. A., Beseler, C. L., Hamby, S., & Wade Jr, R. (2021). Understanding the impact of seeing gun violence and hearing gunshots in public places: findings from the Youth Firearm Risk and Safety Study. Journal of interpersonal violence, 36(17-18), 8835-8851. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260519853393. |

| 57. | Finkelhor et al (2015). Children’s exposure to violence, crime, and abuse: An update. U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention; Rajan, S., Branas, C. C., Myers, D., & Agrawal, N. (2019). Youth exposure to violence involving a gun: evidence for adverse childhood experience classification. Journal of behavioral medicine, 42, 646-657. DOI: 10.1007/s10865-019-00053-0 |

| 58. | One recent study found that 12% of 10-17 year-olds nationwide have had a family member, friend or neighbor die by homicide. Source: Turner, H. A., Finkelhor, D., & Henly, M. (2021). Exposure to family and friend homicide in a nationally representative sample of youth. Journal of interpersonal violence, 36(7-8), NP4413-NP4442. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518787200. Another study found that 11% of 12-17 year-olds nationwide have had a close friend or family member killed by homicide. Source: Rheingold, A. A., Zinzow, H., Hawkins, A., Saunders, B. E., & Kilpatrick, D. G. (2012). Prevalence and mental health outcomes of homicide survivors in a representative U.S.sample of adolescents: Data from the 2005 National Survey of Adolescents. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, 53(6), 687-694.https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2011.02491.x. |

| 59. | Comer, B. P., & Connolly, E. J. (2023). Exposure to gun violence and handgun carrying from adolescence to adulthood. Social science & medicine, 328, 115984. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.Socscimed.2023.115984. |

| 60. | For instance, one study found that “exposure to firearm violence approximately doubles the probability that an adolescent will perpetrate serious violence over the subsequent 2 years.” Source: Bingenheimer, J. B., Brennan, R. T., & Earls, F. J. (2005). Firearm violence exposure and serious violent behavior. Science, 308(5726), 1323-1326. https://doi.org/10.1126/science.1110096. |

| 61. | Panchal, N. (2024). The impact of gun violence on children and adolescents. Kaiser Family Foundation. |

| 62. | Gebeloff, R., Lai, K.K. R., Murray, E., Williams, J. and Lieberman, R. (2024, May 14). How the pandemic reshaped American gun violence. New York Times. |

| 63. | Mitchell, K. J., Jones, L. M., Turner, H. A., Beseler, C. L., Hamby, S., & Wade Jr, R. (2021). Understanding the impact of seeing gun violence and hearing gunshots in public places: findings from the Youth Firearm Risk and Safety Study. Journal of interpersonal violence, 36(17-18), 8835-8851. DOI: 10.1177/0886260519853393. |

| 64. | Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

| 65. | Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration |

| 66. | YRBS Explorer (Youth Risk Behavior Survey). U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. |

| 67. | Results from the 2023 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Detailed Tables. Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. |

| 68. | Lantz, B & Knapp, K.G. (2024). Trends in juvenile offending: What you need to know. Council on Criminal Justice. |

| 69. | Oliphant, S.N., Mouch, C.A., & Rowhani-Rahbar et al. (2019). A scoping review of patterns, motives, and risk and protective factors for adolescent firearm carriage. Journal of behavioral medicine, 42(4), 763–810. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10865-019-00048-x. |

| 70. | Jones, M. S., Boccio, C. M., Semenza, D. C., & Jackson, D. B. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and adolescent handgun carrying. Journal of criminal justice, 89, 102118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2023.102118. |

| 71. | According to a recent study, youth who suffered one type of trauma were 1.8 times more likely to carry weapons than comparable youth with no trauma; and youth with five or more types of trauma were more than five times as likely to carry a weapon than comparable peers with no trauma. Source: Jones, M. S., Boccio, C. M., Semenza, D. C., & Jackson, D. B. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and adolescent handgun carrying. Journal of Criminal Justice, 89, 102118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2023.102118. |

| 72. | Jones, M. S., Boccio, C. M., Semenza, D. C., & Jackson, D. B. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and adolescent handgun carrying. Journal of criminal justice, 89, 102118. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2023.102118; and Mukherjee, S., Taleb, Z. B., & Baiden, P. (2022). Locked, loaded, and ready for school: The association of safety concerns with weapon-carrying behavior among adolescents in the United States. Journal of interpersonal violence, 37(9-10), NP7751-NP7774. DOI: 10.1177/0886260520969403 |

| 73. | White, E., Spate, B., Alexander, J. and Swaner, R. (2023). “Two battlefields”: Opps, cops, and NYC youth gun culture. Center for Justice Innovation. |

| 74. | Simon, T. R. (2022). Gun carrying among youths, by demographic characteristics, associated violence experiences, and risk behaviors—United States, 2017–2019. MMWR. Morbidity and mortality weekly report, 71. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm7130a1. |

| 75. | White, E., Spate, B., Alexander, J. and Swaner, R. (2023). “Two battlefields”: Opps, cops, and NYC youth gun culture. Center for Justice Innovation. |

| 76. | White, E., Spate, B., Alexander, J. and Swaner, R. (2023). “Two battlefields”: Opps, cops, and NYC youth gun culture. Center for Justice Innovation. |

| 77. | Wallace, L. N. (2017). Armed kids, armed adults? Weapon carrying from adolescence to adulthood. Youth violence and juvenile justice, 15(1), 84-98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541204015585363. |

| 78. | Mattson, S. A., Sigel, E., & Mercado, M. C. (2020). Risk and protective factors associated with youth firearm access, possession or carrying. American journal of criminal justice, 45(5), 844-864. DOI: 10.1007/s12103-020-09521-9; Webster, D. W., Meyers, J. S., & Buggs, M. S. (2014, February). Youth acquisition and carrying of firearms in the United States: Patterns, consequences, and strategies for prevention. In Proceedings of Means of violence workshop, forum of global violence prevention. Washington, DC: Institutes of Medicine of the National Academies. |

| 79. | Lurie, S. (2019, February 25). There’s no such thing as a dangerous neighborhood. Bloomberg. |

| 80. | Center for Gun Violence Solutions (n.d.) In depth: Community Gun Violence (web page). Bloomberg School of Public Health, Johns Hopkins University. |

| 81. | In September 2024, Gault Center emailed a survey questionnaire about handling of gun possession cases to the 108 members of its national advisory board and its nine regional advisory boards, and to the Gault Center’s larger mailing list of more than 1,000 youth defenders and other youth justice professionals nationwide. |

| 82. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention. |

| 83. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A hidden key to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project. |

| 84. | Mycofski, M. (2024, January 11). Health advocates criticize New Mexico governor for increasing juvenile detention. KUNM public radio. |

| 85. | Mycofski, M. (2024, January 11). Health advocates criticize New Mexico governor for increasing juvenile detention. KUNM public radio. |

| 86. | Utah HB 362 (2024). |

| 87. | Florida HB 1181 (2024). |

| 88. | Georgia Code § 15-11-602 (2024). |

| 89. | NY State Penal Law § 265.03 (3). Criminal Possession of a Weapon in the Second Degree (Possession of Loaded Firearm Not in Home or Business). |

| 90. | Maryland Governor’s Office of Crime Prevention and Policy. (2025, Feb. 21). Youth Charged as Adults. Meeting of Commission on Juvenile Justice Reform & Emerging Best Practices. |

| 91. | Maryland Department of Juvenile Services (2024). Data Resource Guide, Fiscal Year 2024, p. 107. See: “ALOS (Average Length of Stay) By Placement Type, FY2022-2024.” |

| 92. | |

| 93. | Illinois Compiled Statutes: 720 ILCS Sec. 24-1.6. |

| 94. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. U.S. Office of Juvenile Justice & Delinquency Prevention. |

| 95. | Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2007). Effects on violence of laws and policies facilitating the transfer of youth from the juvenile to the adult justice system: A report on recommendations of the task force on community preventive services. MMWR 2007; 56 (No. RR-9). |

| 96. | Mendel, R. (2023). Why youth incarceration fails: An updated review of the evidence. The Sentencing Project. |

| 97. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A hidden key to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project. |

| 98. | Lowenkamp, C. T., Latessa, E. J., & Holsinger, A. M. (2006). The risk principle in action: What have we learned from 13,676 offenders and 97 correctional programs?. Crime & Delinquency, 52(1), 77-93. DOI: 10.1177/0011128705281747. |

| 99. | Carey N, Coley RL. (2022). Prevalence of Adolescent Handgun Carriage: 2002–2019. Pediatrics, 149(5):e2021054472. DOI: 10.1542/peds.2021-054472; Youth Risk Behavior Surveillance – United States (1993-2023). Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report. U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (See links here for 2017-2023 and for prior years in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report). |

| 100. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice; Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A. and Kang, W. (2024). Easy Access to Juvenile Populations: 1990-2022. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 101. | Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A., and Kang, W. (2023). Easy Access to Juvenile Court Statistics: 1985-2021. National Center for Juvenile Justice; Puzzanchera, C., Sladky, A. and Kang, W. (2024). Easy Access to Juvenile Populations: 1990-2022. National Center for Juvenile Justice. |

| 102. | Engel, R., Hatch, A. & Acampora, M. (2020). Policing Guns and Gun Violence: A Toolkit for Practitioners and Advocates. National Network for Safe Communities at John Jay College. |

| 103. | Mendel, R. (2022). Diversion: A hidden key to combating racial and ethnic disparities in juvenile justice. The Sentencing Project. |

| 104. | Bryant, E. (2022). Locking Teenagers and Young Adults Up for Gun Possession Doesn’t Make Us Safer. Vera Institute of Justice. |

| 105. | Email from Colin Slay, Court Administrator, Clayton County Juvenile Court (November 19, 2024); and Jones, T. (2024, May 6). ‘I’m not trying to go back to jail:’ Judge creates program after many Clayton teens found with guns. WSB TV Atlanta. |

| 106. | Interview with Deborah Garcia Sandoval, Probation Officer/ Handgun Intervention Program HIP-Coordinator, Denver County Juvenile Court Probation, December 11, 2024. |

| 107. | Soe-Lin, H., Sarver, A., Kaufman, J., Sutherland, M., & Ginzburg, E. (2020). Miami-Dade County Juvenile Weapons Offenders Program (JWOP): a potential model to reduce firearm crime recidivism nationwide. Trauma surgery & acute care open, 5(1). |

| 108. | The Youth PACT program is a gun possession diversion program for youth that is operated by the Midtown Community Justice Center, a part of the Center for Justice Innovation in New York City. Source: Youth PACT Fact Sheet (n.d.) Midtown Community Justice Center. |

| 109. | Colombini, S. (2023, December 11). More kids are getting arrested with guns. A Tampa program aims to turn their lives around. WUSF Radio. |

| 110. | Epperson, M. W., Garthe, R. C., Lee, H., & Hawken, A. (2024). An examination of recidivism outcomes for a novel prosecutor-led gun diversion program. Journal of Criminal Justice, 92, 102196. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcrimjus.2024.102196; Caiola, S. (2024, February 14). Philly DA’s illegal gun possession diversion program reports a 76% decrease in re-arrests among participants. Kensington Voice. |

| 111. | Colombini, S. (2023, December 11). More kids are getting arrested with guns. A Tampa program aims to turn their lives around. WUSF Radio. |

| 112. | Zoom interview with Freddie Barton, executive director, Safe and Sound Hillsborough, Tampa, FL. December 18, 2024. |

| 113. | Denver Juvenile Handgun Intervention Program Youth & Family Handbook (n.d.). Colorado Courts, provided to the author by Deborah Garcia Sandoval, Probation Officer/ Handgun Intervention Program HIP-Coordinator, Denver County Juvenile Court Probation, December 2024. |

| 114. | Telephone interview with Deborah Garcia Sandoval, Probation Officer/ Handgun Intervention Program HIP-Coordinator, Denver County Juvenile Court Probation, December 11, 2024. |

| 115. | Organizations supporting comprehensive approaches to youth gun violence include: American Academy of Family Physicians; American Academy of Pediatrics; American Psychological Association; Johns Hopkins University Center for Gun Violence Solutions; Joyce Foundation; National Academy of Medicine; and the U.S. Surgeon General. |

| 116. | A Second Chance: The Case for Gun Diversion Programs (2021). Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence. |

| 117. | Gebeloff, R., Lai, K.K. R., Murray, E., Williams, J. and Lieberman, R. (2024, May 14). How the pandemic reshaped American gun violence. New York Times. |

| 118. | Lurie, S. (2019, February 25). There’s no such thing as a dangerous neighborhood. Bloomberg. |

| 119. | Delgado, S. A., Alsabahi, L., Wolff, K., Alexander, N., Cobar, P., & Butts, J. A. (2021). Denormalizing violence: A series of reports from the John Jay College evaluation of cure violence programs in New York City. |

| 120. | National Network for Safe Communities (2020). Group Violence Intervention Issue Brief. John Jay College. |

| 121. | Corburn, J., Nidam, Y., & Fukutome-Lopez, A. (2022). The art and science of urban gun violence reduction: evidence from the advance peace program in Sacramento, California. Urban Science, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010006. |

| 122. | Corburn, J., Nidam, Y., & Fukutome-Lopez, A. (2022). The art and science of urban gun violence reduction: evidence from the advance peace program in Sacramento, California. Urban Science, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/urbansci6010006. |

| 123. | Giffords Law Center to Prevent Gun Violence (2023). Implementing the Bipartisan Safer Communities Act: One Year In. |

| 124. | This figure ($820 million) reflects the cancelled grant programs’ total initial award value, some of which had already been expended before the recent decision to terminate funding. The Council of Criminal Justice has estimated that collectively, grantees lost an estimated $500 million in remaining funding, (roughly 60% of the total). Source: Council on Criminal Justice (2025). DOJ Funding Update: A Deeper Look at the Cuts. |

| 125. | Council on Criminal Justice (2025). DOJ Funding Update: A Deeper Look at the Cuts. |

| 126. | Council on Criminal Justice (2025). DOJ Funding Update: A Deeper Look at the Cuts. |

| 127. | Steinberg, L. (2009). Adolescent development and juvenile justice. Annual review of clinical psychology, 5(1), 459-485. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.032408.153603. |

| 128. | Lipsey, M. W., Landenberger, N. A., Wilson, S. J., & Lipsey, M. (2007). Effects of cognitive-behavioral programs for criminal offenders. Campbell Systematic Reviews, 6. |

| 129. | Mendel, R. (2023). Effective alternatives to youth incarceration. The Sentencing Project. |

| 130. | Building safer communities: Behavioral science innovations in youth violence prevention (2024). University of Chicago Crime Lab. |