Vermont Should Give a Second Look at Extreme Sentences

Vermont’s prison population has declined over 30% since reaching its peak in 2009. However, the number of people serving Vermont’s most extreme sentence, life without the possibility of parole, has only increased, standing at odds with the state’s attempts to scale back prison growth.

Related to: Sentencing Reform, State Advocacy

Vermont’s prison population has declined over 30% since reaching its peak in 2009.1 Policy reforms prioritized by state lawmakers and practitioners over the years can be credited with this impressive outcome. Over this same time period, however, the number of people serving Vermont’s most extreme sentence, life without the possibility of parole, has only increased, standing at odds with the state’s attempts to scale back prison growth.

Life sentences with no chance for review or release contradict the well-documented and predictable patterns in criminal conduct. People who have committed crime, even violent crime, have relatively short criminal careers and tend to commit crime in their youth and young adulthood.2 Excessively long sentences that carry into one’s middle-age and elderly years, as well as those that extend beyond 20 years, provide diminishing public safety benefits.

Legislative proposals that follow the science with regard to criminal sentences secure a functional corrections system that is responsive to community needs for both accountability and crime control. Legislators are urged to reform the criminal sentencing structure in these ways:

- End life without parole (LWOP);

- Limit the use of consecutive sentences that mimic life without parole (LWOP) in their outcome; and

- Establish a “second look” mechanism for all sentenced individuals that permits due process protections for people seeking earned release after 10 years or 50% of their sentence.

None of these reforms guarantee freedom. Instead, current legislative proposals place emphasis on examining the rehabilitation of the individual, understanding that age is a mitigating factor in reckless conduct, and abolish the use of perpetual imprisonment.

Life Sentences in Vermont

Vermont’s Department of Corrections reports a total of 174 people, or 20% of the state prison population (851 sentenced individuals3, serving sentences of life with parole (151), life without parole (14), or a virtual life sentence of 50 years or more (9).4 Vermont far surpasses the national average in terms of imprisonment length. Nationally, one in 7 people in prison is serving a life sentence; in Vermont, it’s one in 5. Vermont has more people serving life sentences today than its entire prison population in 1970, just before the start of the mass incarceration era.5

Lawmakers could substantially reduce the burdens of long term imprisonment by using common sense reforms that prioritize public safety and fiscal responsibility while allowing deserving individuals a second look. Vermont is a national leader in overall decarceration efforts, but thus far excludes people serving long sentences from benefiting from these efforts.

Age, Gender, Race, and Time Served

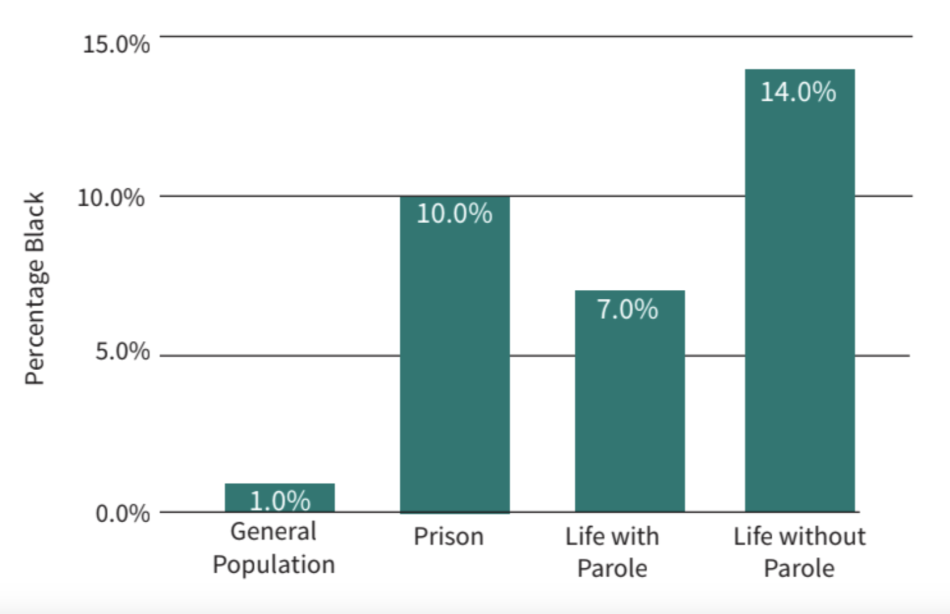

As with national trends, the majority of people serving life sentences in Vermont are men; three women in Vermont are serving LWOP. The vast majority of Vermonters are white, with only a 1% population of residents being Black. As with all states, racial disparity becomes evident with imprisonment. Though overall numbers are small, the rate of Black imprisonment is disproportionately high.

Figure 1. Black Vermonters in General Population, Prison, and Serving Life Sentences

At approximately 50 years old, experts consider incarcerated individuals to be elderly due to their harsh living conditions that result in accelerated aging.6 Unlike the national trends, which finds that about one third of people in prison are considered elderly, most of the people serving life sentences in Vermont are over 50.7

Many individuals serving extreme sentences in Vermont have already served at least two decades in prison; the average time served among people serving LWOP in the state is 22 years, with a range from 7 years to 37 years. For people serving life sentences with parole, the average is 14 years with a range from 2 to 38 years.

Growth of Life Sentences in Vermont

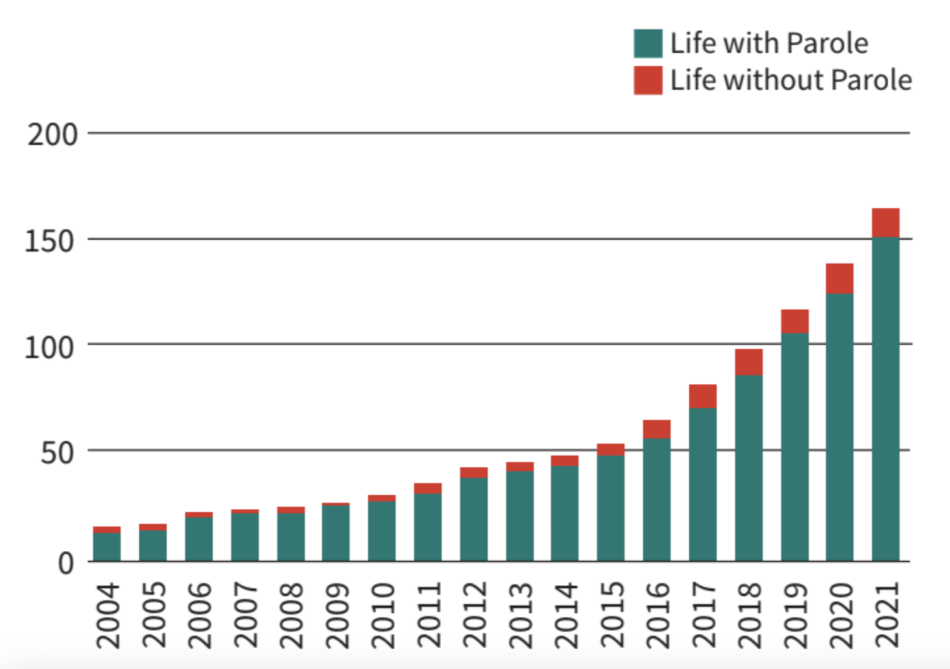

The expansion of life sentences in Vermont echoes a trend toward longer sentences more generally. Notably, the pace of growth of life sentences with parole (LWP) has been swifter in Vermont than in nearby states and the national average. Since 2003, Vermont has doubled the number of people serving life sentences: more than 150 people are serving such sentences today, while the state has also experienced substantial declines in the overall prison population.

Figure 2. Annual Growth of People serving Life with Parole and Life without Parole

Conclusion

Vermont lawmakers should follow the science regarding sentencing policy in its decision-making. The financial and societal costs of heavy reliance on life sentences far outweighs its hoped-for benefits.8 Instead, a wide body of research has concluded that the deterrent effect from crime is more a function of certainty of punishment rather than severity.9 Moreover, imprisoning people long past their proclivity— or even physical ability—to commit crime is a poor use of resources that could be better put toward crime prevention and community-building.

Ending life and other long sentences would position Vermont as a national leader in addressing structural racism and mass incarceration.

Vermont is among several jurisdictions, including Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Michigan, New York, and Pennsylvania, that are considering proposals that improve parole practices for life-sentenced people and others serving long prison terms. Establishing a “second look” mechanism for all sentenced individuals that permits due process protections for people seeking earned release after 10 years or 50% of their sentence would brings a level of much-needed compassion back into the system.

| 1. | Ghandnoosh, N. (2021). Can we wait 60 years to cut the prison population in half? The Sentencing Project. |

|---|---|

| 2. | Cauffman, E. & Steinberg, L. (2000). (Im)maturity of judgment in adolescence: Why adolescents may be less culpable than adults. Behavioral Sciences and the Law, 18(6), 741-760; Scott, E., & Steinberg, L. (2010). Rethinking juvenile justice Boston: Harvard University Press; Steinberg, L. & Scott, E. (2003). Less guilty by reason of adolescence: Developmental immaturity, diminished responsibility, and the juvenile death penalty. American Psychologist, 58(12), 1009-1018. |

| 3. | Vermont Department of Corrections (2022). Population report, 12-31-2022. |

| 4. | The Sentencing Project defines this term of imprisonment as “virtual life” because it is likely impossible, given the media age at sentencing, to survive 50 years in prison. Nellis, A. (2021). Elderly lifers. |

| 5. | Nellis, A. (2021). People serving life exceeds entire prison population in 1970. The Sentencing Project. |

| 6. | Williams, B. A., Goodwin, J. S., Baillargeon, J., Ahalt, C., & Walter, L. C. (2012). Addressing the aging crisis in U.S. criminal justice health care. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 60(6), 1150–1156. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-5415.2012.03962.x |

| 7. | Vermont Department of Corrections data. |

| 8. | Nagin, D. (2013). Deterrence: A review of the evidence by a criminologist for economists. American Review of Economics 5, 83-105. |

| 9. | Von Hirsch, A et al (1999) “Criminal Deterrence and Sentence Severity: An Analysis of Recent Research,” Oxford: Hart Publishing. |